Two invisible stars are bending space-time deep in the Milky Way

The stars are turning the space between them into a field of cosmic magnifying glasses, and that's screwing with our view of a star much farther away.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In summer 2016, astronomers watched a star 2,500 light-years away in the Cygnus constellation flash to life as if preparing to explode in a fiery supernova. The next day, however, the star dimmed back to normal again — no fuss, no kaboom. Within a few weeks, the strange cycle repeated itself: The star suddenly brightened, then dimmed again within a day. Over the following year, the cycle occurred again and again, repeating five times within 500 days.

"This was a very unusual behavior," Łukasz Wyrzykowski, an astronomer who studied the strange star at the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, Poland, said in a statement. "Hardly any type of supernova or other star does this."

Related: 9 Epic Space Discoveries You Probably Missed in 2019

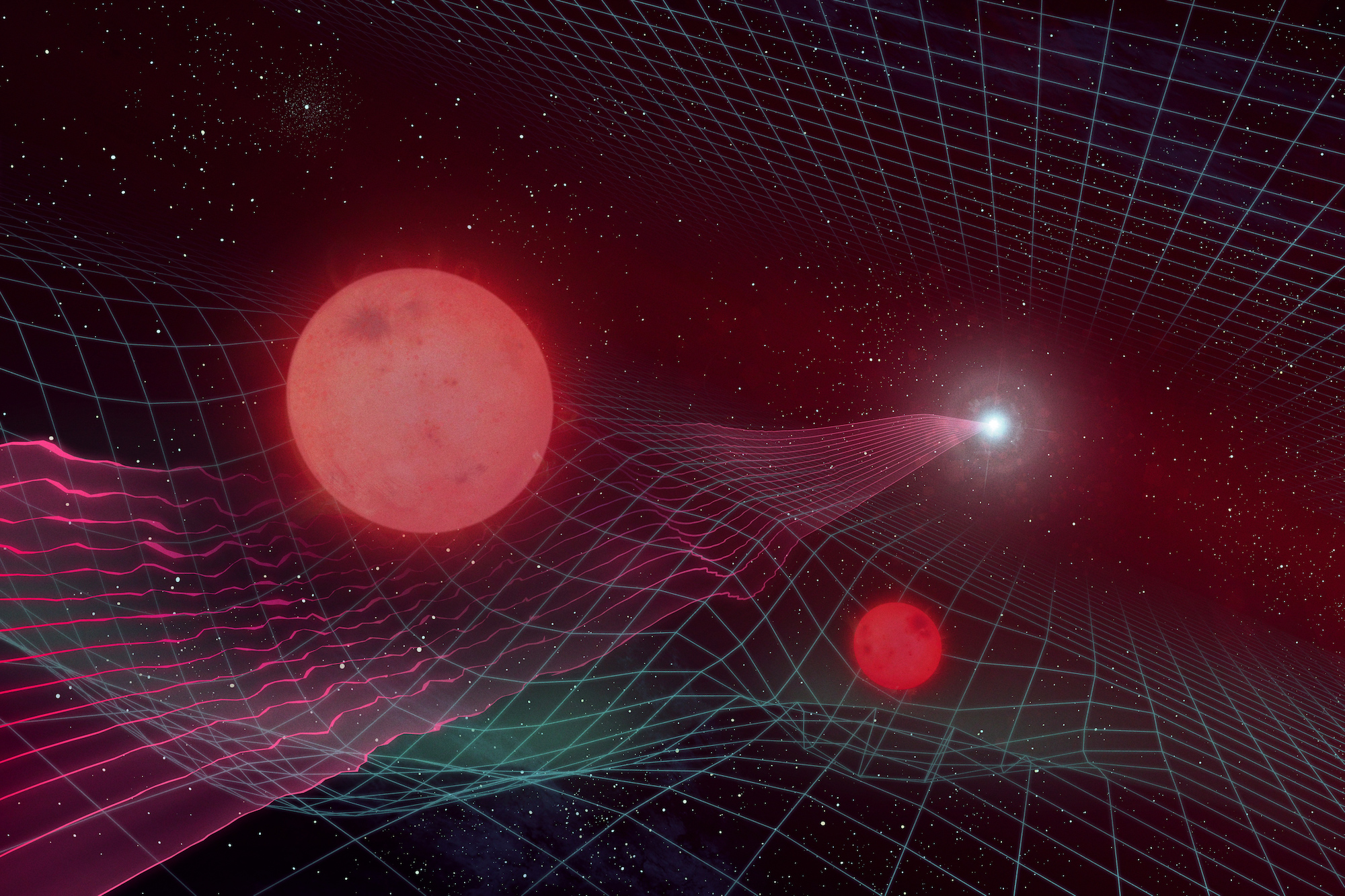

Now, according to a study published Jan. 21 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, it turns out that the oddball star, named Gaia16aye, wasn't doing anything out of the ordinary at all. Rather, the study authors wrote, it appears that a set of meddlesome binary stars (two stars that orbit around a shared gravitational center) is warping space-time in front of Gaia16aye, effectively creating a field of cosmic magnifying glasses. These lenses amplify the star's light every time it passes behind them. And those stars were effectively invisible from Earth.

This stellar magnifying effect, wherein massive objects seem to bend space-time around them, is known as gravitational lensing and was predicted by Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. Scientists have since used the phenomenon to get a closer look at some of the oldest stars, galaxies and objects in the universe, but the effect can also reveal the properties of much closer, dimmer objects.

Take, for example, the binary pair that's messing with Gaia16aye. While the duo appear totally invisible to us, the strength and frequency of their gravitational lensing allowed the researchers to work backward and determine "basically everything" about them, study co-author Przemek Mróz, a postdoctoral scholar at the California Institute of Technology, said in the statement.

The team concluded that in order to produce the frequent, daylong brightening of Gaia16aye, the binary pair must be creating not one, but multiple pockets of magnification (also known as gravitational microlensing). That means these stars are likely a pair of small, red dwarfs roughly 0.57 and 0.36 times the mass of Earth's sun, separated by about twice the Earth-sun distance, the study authors found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If microlensing events like this one can reveal invisible stars, such happenings may also be able to uncover even rarer, more mysteries cosmic phenomena. Hopefully, the researchers said, that will include black holes, which are normally detectable only when they're scarfing down nearby matter and burping up jets of gassy light. The Milky Way could be loaded with millions of stand-alone black holes too far from any nearby stars to put on such a light show, the researchers said, and gravitational lensing could be the key to finding them. If an invisible black hole creates a lensing effect that distorts the light behind it, astronomers can work backwards to reveal its true nature.

- 9 ideas about black holes that will blow your mind

- The 15 weirdest galaxies in our universe

- The 12 strangest objects in the universe

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus