In extremely rare case, doctors remove fetus from brain of 1-year-old

A young child had the remnants of her absorbed twin removed from her head.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In an extremely rare case, doctors surgically removed a fetus from the brain of a 1-year-old child. Doctors found the fetus after the child showed delayed motor skill development, an enlarged head circumference and a buildup of fluid in the brain.

The report, published Dec. 12, 2022, in the journal Neurology, noted that the mass in the young child's head was a "malformed monochorionic diamniotic twin," meaning in the womb, the fetuses had once shared the same placenta but had separate amniotic sacs, the thin-walled, liquid-filled sacs that surround fetuses as they develop. These types of twins come from the same fertilized egg, meaning they're identical.

The anomaly in which one fetus becomes enveloped by another is known as "fetus in fetu," or sometimes "parasitic twin." The absorbed twin typically stops developing while the other continues to grow, the Miami Herald reported.

The phenomenon occurs in an estimated 1 in 500,000 live births; usually, the malformed fetus appears as a mass in the other fetus's abdomen, wedged behind the tissues that line the abdominal wall. However, in this case, the mass appeared in the "host" fetus's head, and likely arose very, very early in development, at the stage when the fertilized egg forms a cluster of cells called a blastocyst.

Related: Did you share the womb with a 'vanishing twin'? The answer may be written in your DNA.

"The intracranial fetus-in-fetu is proposed to arise from unseparated blastocysts," meaning the cell clusters that were destined to grow into two separate fetuses stayed stuck together, the case report authors wrote. "The conjoined parts develop into the forebrain of host fetus and envelop the other embryo during neural plate folding." (The neural plate is a structure that forms in early development and gives rise to the nervous system.)

"Intracranial fetus in fetu is extremely rare with <20 reports published worldwide," a 2020 case report in the journal World Neurosurgery noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

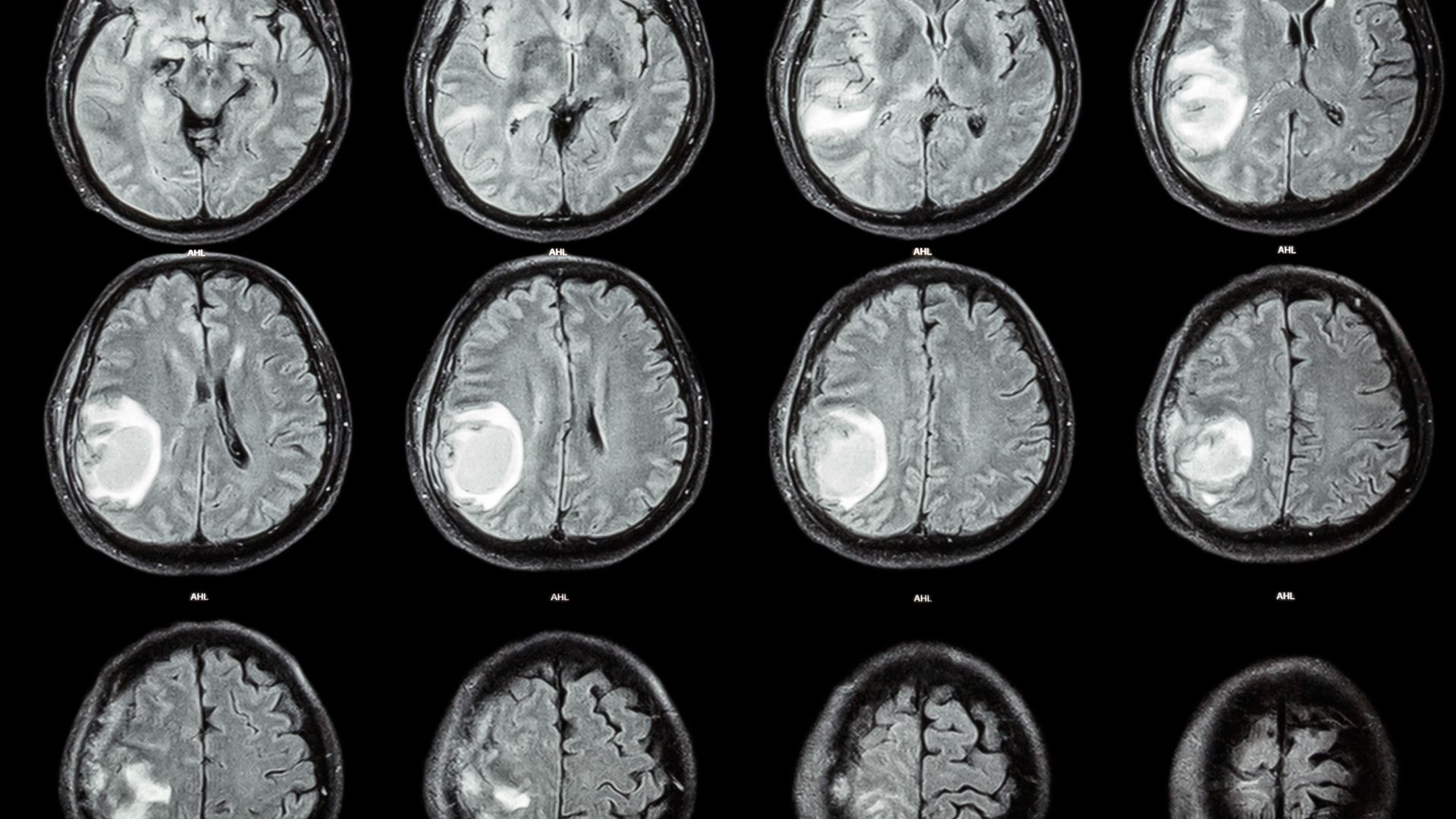

Brain scans of the 1-year-old child's head revealed that the fetus contained a vertebral column and two leg bones (the femur and tibia), and that the malformed fetus had spina bifida, a condition in which part of the spinal cord is exposed, rather than covered by tissues of the back, due to a problem during development. Once removed, the fetal mass was also determined to have "upper limb and finger-like buds."

The brief case report does not include details of the 1-year-old's condition following surgery.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus