Here's How a Princeton Physicist Lost Classified H-Bomb Documents in 1953 … on a Night Train

Details of the debacle have been made public for the first time.

Perhaps you've recently forgotten where you parked your car, or lost track of your house keys or your phone. You're still better off than the physicist who in 1953 misplaced secret government documents about the first hydrogen bomb.

John Archibald Wheeler was a pioneer in physics, blazing trails in the fields of quantum theory and nuclear fission; he is even credited with coining the term "black hole." But one of his lesser-known escapades involved the disappearance of highly sensitive files describing H-bomb tests. The classified pages weren't lost in a black hole but during a train trip, after a visit to the bathroom.

How did that happen? A science historian dug up the long-buried tale of the H-bomb secrets that mysteriously vanished nearly 70 years ago, revealing the details of the disappearance to the public for the first time.

Related: 7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare

Wheeler's FBI file was recently released under the Freedom of Information Act, and Alex Wellerstein — an assistant professor in science and technology studies at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey — decided to investigate what happened on that fateful train ride. Wellerstein retraced Wheeler's steps to piece together how the files went missing, detailing his findings online Dec. 1 in the journal Physics Today.

During the 1940s, scientists opened a Pandora's Box with the development of the first atomic bomb, unleashing weapons of previously unimaginable destructive power. After World War II ended, research continued to unlock a "super-bomb" — hydrogen bombs triggered by atomic fusion, a process that generates explosions hundreds of times more potent than the fission bombs that decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

The main U.S. site for work on hydrogen bombs was located in Savannah River, South Carolina. But at Princeton University, where Wheeler was a professor, he created and managed an H-bomb project known as Matterhorn B — the "B" stood for "bomb," Wellerstein reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

'Completely vaporized'

A U.S. task force detonated the first hydrogen bomb on Nov. 1, 1952, at Eniwetok Atoll in the South Pacific's Marshall Islands, according to U.S. Army archives. The blast radius "was ten times that of an atomic explosion and 1,000 times as powerful as an atomic blast," according to the archive. The island of Elugelab, where the test took place, was "completely vaporized."

Not all American scientists and officials supported the creation of such apocalyptic weapons. But H-bomb supporters claimed that it was imperative for the U.S. to keep up with atomic weapons development that was underway in the Soviet Union.

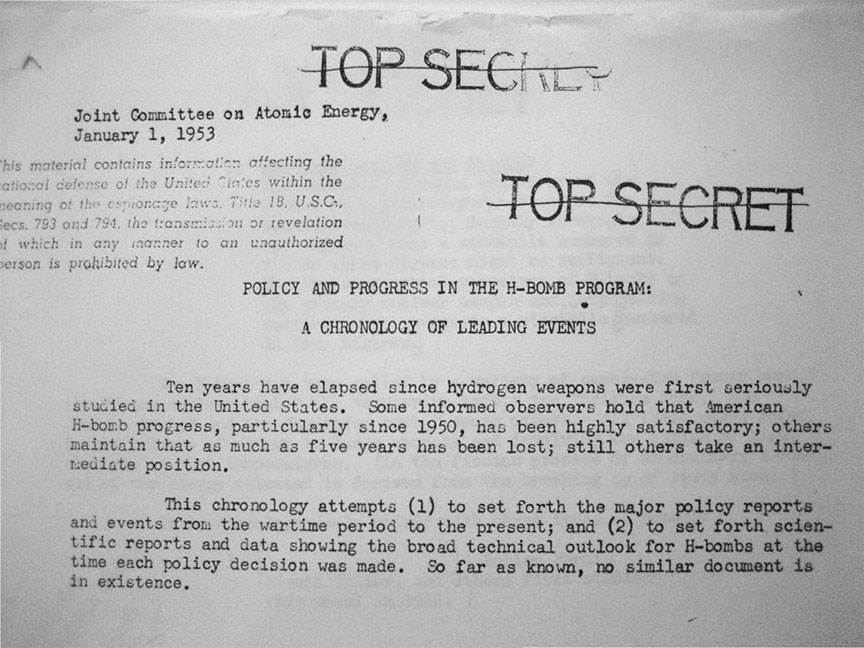

To bolster arguments for H-bomb research and tests, the congressional team overseeing U.S. atomic programs — the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy — produced a 91-page document outlining the history of the H-bomb program up to the successful tests, and a six-page excerpt was sent to Wheeler to review.

Those documents — classified as "secret" rather than "top-secret" because of Wheeler's lower security clearance — would be taken by Wheeler on an overnight train trip from Princeton to Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 1953.

Related: The 10 Most Dangerous Space Weapons Ever

Night train

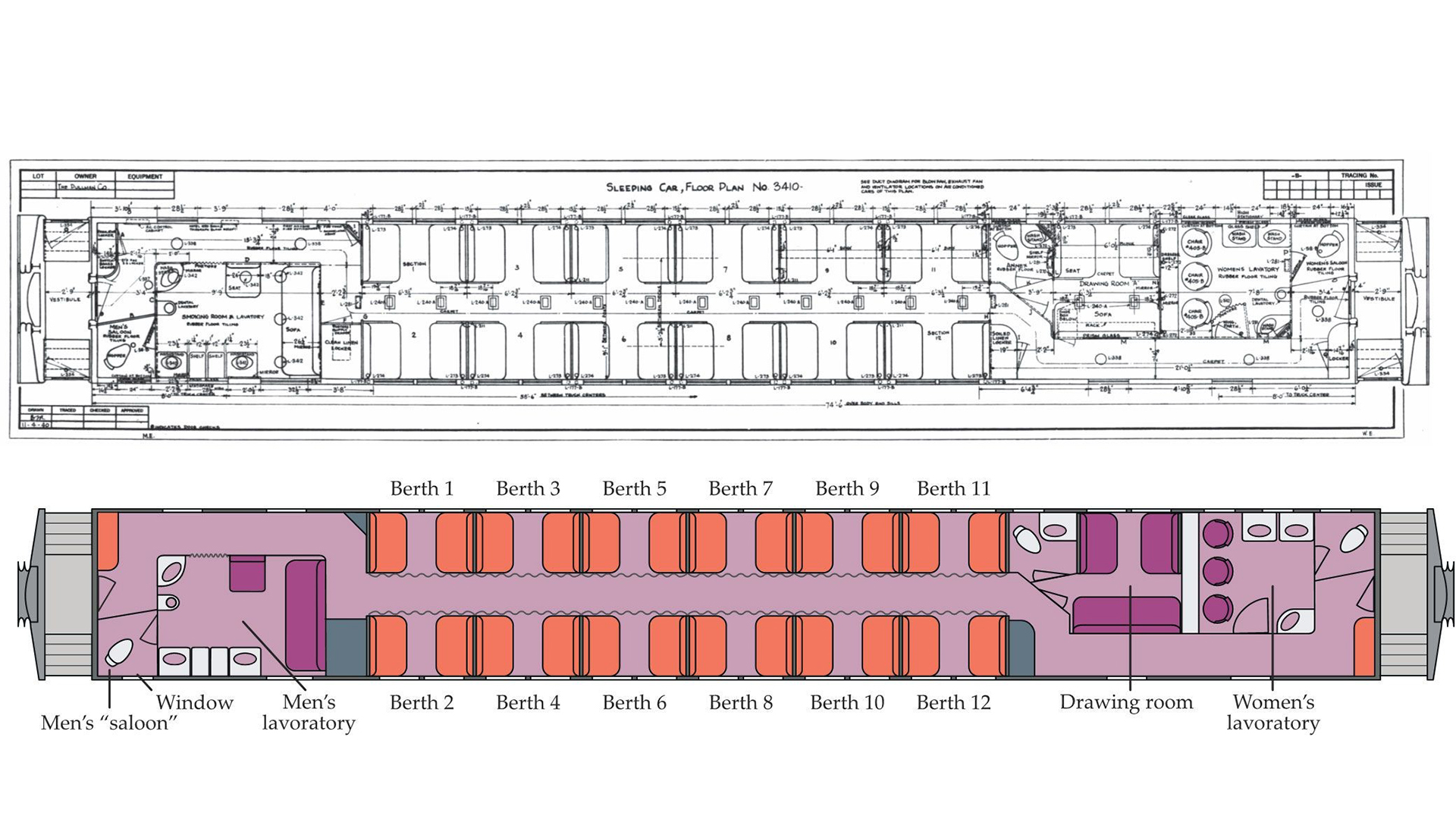

In the study, Wellerstein outlines Wheeler's actions as he prepared for the journey. Wheeler placed the pages in a white envelope and boarded the first of several trains in Princeton at 9:01 p.m. local time. By 10:10 p.m., he was en route to Washington in a sleeper car.

Wheeler later told FBI agents that he took the secret papers out of their white envelope and read them in his berth before he went to sleep. When he awoke in the morning, he placed the white envelope inside a larger manila envelope and brought it into the washroom.

After leaving the washroom, he realized that he had left the envelope behind in a toilet stall, and dashed back to recover it. The manila envelope looked unopened, but when Wheeler checked it later, the white envelope — and the H-bomb files — weren't there. An increasingly desperate Wheeler hunted fruitlessly for the missing nuclear secrets, and the FBI was called in to take over the search.

FBI records describe exhaustive efforts to track down the documents: They conducted numerous interviews and dismantled Wheeler's sleeper car piece by piece to uncover any possible hiding place for the wayward files. Officials even considered assigning federal agents to walk the train tracks all the way from Philadelphia to Washington, in case the papers had been discarded (that idea was ultimately abandoned).

In the end, the FBI concluded that the fate of the missing documents likely had nothing to do with espionage, and their disappearance — even if the investigation couldn't discover exactly how it happened — was accidental and mundane.

"The most likely scenario was that Wheeler didn't put it back in the envelope after reading it that night on the train and that it was somehow swept up into the trash and destroyed," Wellerstein wrote in the study.

"But if that were true, it would be impossible to verify."

- The 10 Greatest Explosions Ever

- Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets

- Mind-Controlled Cats?! 6 Incredible Spy Technologies That Are Real

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus