Tick transforms into a glowing alien from a sci-fi nightmare in trippy photo

Outstanding examples of stunning microscopy were recently honored in the Nikon Small World contest.

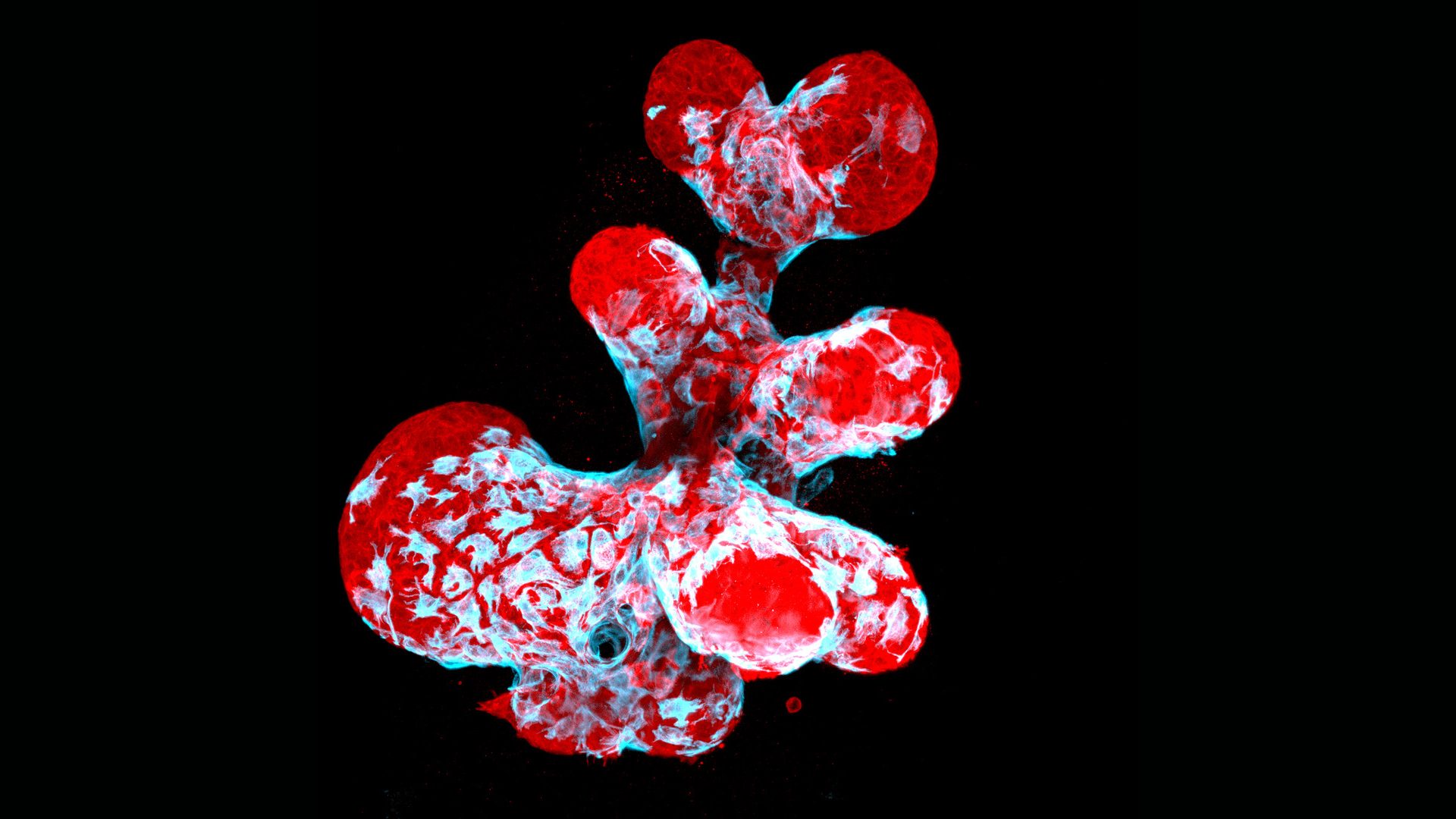

A prizewinning microscopy image of a tick's head rendered in psychedelic colors may change the way you look at bloodsucking parasites.

The intense magnification — combined with glowing hues that illuminate the creature's protruding head, internal structures and armored, spiky exoskeleton — make the tick seem more like a bizarre (or beautiful?) visitor from another world.

The image offers a perspective of the tiny arthropod that you've probably never seen before. And that's exactly the point of this and other standout entries that were recently honored in the Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition, now in its 47th year. The tick photo, and more than 100 others chosen for the contest's top awards, showcase the science and beauty of organisms, minerals and other objects that are too small to be seen with the naked eye.

Related: Magnificent microphotography: 50 tiny wonders

However, for a microscopy image to really stand out from the pack, it's not enough for it to just look beautiful, said contest judge Alexa L. Mattheyses, an associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine.

Instead, an image also has to trigger your curiosity. "Does it spark something in you; do you want to know more about it?" Mattheyses told Live Science. "The subject matter is so diverse; that's where having a diverse panel of judges comes into play, because we're all drawn to different things," Mattheyses said.

On one level, judging the photos required looking at them "like any other kind of art," said contest judge Hank Green, a YouTube content creator, author and science communicator.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We talked about how the images made us feel, their composition, the stories they told, the techniques that were used," Green told Live Science in an email. "There was special attention paid to things that anyone could enjoy, but that enjoyment would get deeper when you understood it more deeply."

For the contest, five judges evaluated nearly 1,900 submissions from 88 countries, awarding the tick image seventh place overall. It was captured by researchers Paul Stoodley, director of Ohio State University's Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility (CMIF), and Tong Zhang, CMIF's associate director and senior microscopist, using confocal microscopy, which focuses laser light on a subject while a pinhole lets in a very small amount of light and blocks the parts of the image that are out of focus.

"People can see some fine details in this tick head, and especially its mouth region with [an] inverted-arrow-like structure. Ticks use this kind of structure to anchor them on animals," Zhang told Live Science in an email. The image's color scheme made the mouth region stand out from the rest of the head, he said.

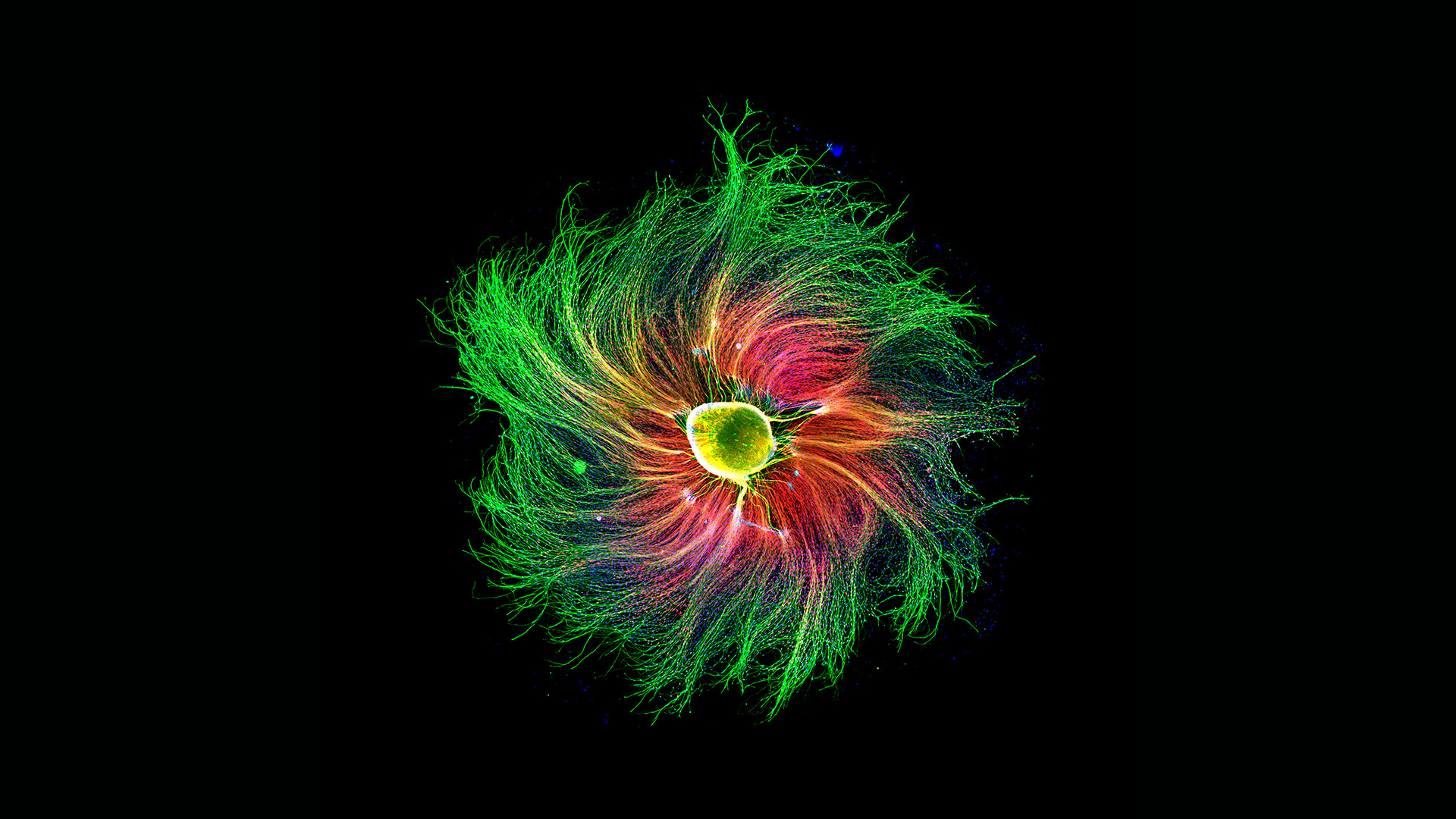

The competition's first place award went to Jason Kirk, technical director of the Optical Imaging and Vital Microscopy Core at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, for his image of the underside of an oak leaf and its delicate, protective structures called trichomes. The photo shows the leaf's white trichomes nestled among pink pores, where they resemble tentacled sea anemones.

"This photograph is really the result of an experimental microscope system that I was building at home," Kirk told Live Science. When Kirk's daughter brought in an oak leaf to test the equipment, he was intrigued by the trichomes on the leaf's underside. For the contest photo, Kirk collected newly sprouted oak leaves in which the trichomes were just starting to emerge.

"The biggest technical challenge was lighting," he said. Illuminating the tiny structures required delicately balancing the color and temperature of three light sources: one on top of the leaf, one underneath and one on the side that lit up the trichomes.

The oak leaf "was something that was in our backyard and something that we interact with every day, but you don't really have an appreciation for what it really looks like up close," he said. "I hope that it makes people look a little bit harder at the things that are right under their feet."

"Being able to see all the beautiful images that scientists as well as amateur scientists took and submitted, it does open your mind up to different ways to acquire images, and different types of information you can get out of them," Mattheyses said. "I found it really inspiring and energizing to be able to do that judging, and then go back to my own work and see some new stuff!"

For those of us who don't regularly peer through microscopes at tiny wonders, seeing these images can still be a transformative experience, Green said.

"I think the more time you spend in the microcosmos, the better your appreciation for everything," he said. "If you pay enough attention it can take you from, 'Why doesn't anything work in this broken world?' to 'It's so awe-inspiring that anything works at all.'"

You can see all of the contest's top 20 winners and honorable mentions on the Nikon Small World website.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.