Galaxy-size shock waves found rattling the cosmic web — the largest structure in the universe

Astronomers have detected enormous shockwaves rattling the cosmic web that connects all galaxies in the universe, offering vital clues on how the largest structures in space were shaped.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For the first time, astronomers have spotted enormous, galaxy-scale shock waves rattling the "cosmic web" that connects nearly all known galaxies. These cosmic waves could reveal clues about how the largest objects in the universe were sculpted.

The discovery was made by stitching and stacking thousands of radio telescope images together, which revealed the soft "radio glow" produced by shock waves from colliding matter in our universe's biggest structures.

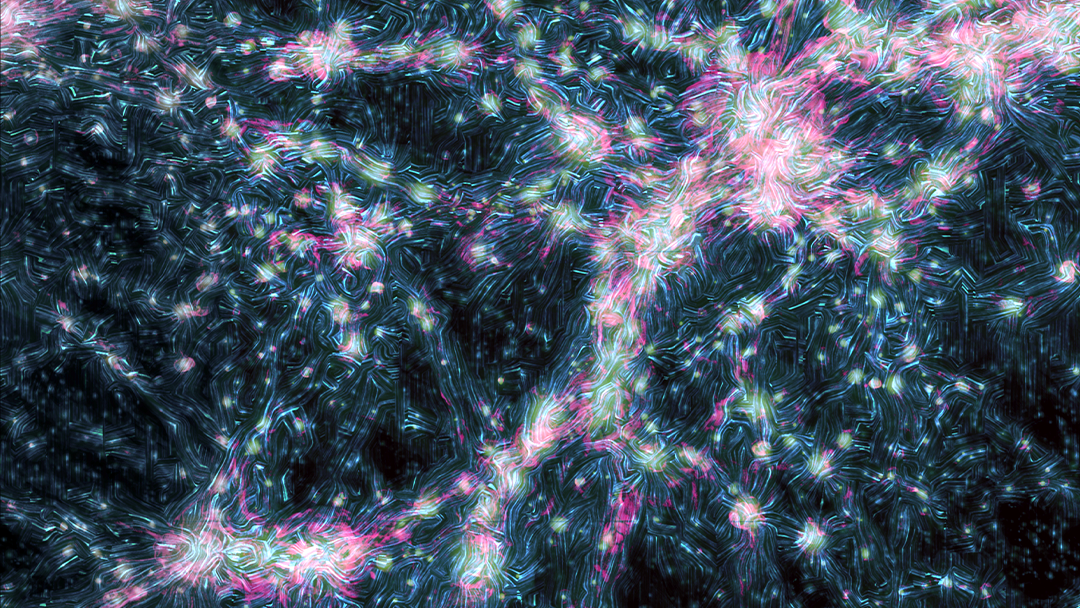

The cosmic web is a gigantic network of crisscrossing celestial superhighways paved with hydrogen gas and dark matter. Galaxies tend to form where multiple strands of the web intersect, often in clusters numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Now a new study, published Feb. 15 in the journal Science, could provide vital clues into the nature of the mysterious magnetic fields that stretch beside these tendrils.

Related: New map of the universe's matter reveals a possible hole in our understanding of the cosmos

"Magnetic fields pervade the universe — from planets and stars to the largest spaces in-between galaxies," lead author Tessa Vernstrom, an astronomer at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Crawley, Australia, said in a statement. "However, many aspects of cosmic magnetism are not yet fully understood, especially at the scales seen in the cosmic web."

Taking shape in the chaotic aftermath of the Big Bang, the cosmic web's tendrils formed as clumps of matter from the roiling particle-antiparticle broth of the young universe — whose rapid expansion pushed the filaments outwards to form an interconnected soap-sud structure of thin films surrounding countless, mostly empty voids.

Far from being completely frozen in place, the cosmic web's matter can sometimes violently collide. When matter in the web merges, enormous shock waves send charged particles ricocheting through the web's magnetic fields, causing the particles to emit a faint radio wave glow. These shock waves have been spotted around some of the universe's largest galaxy clusters, but until now they were never observed around the web itself.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These shock waves give off radio emissions which should result in the cosmic web 'glowing' in the radio spectrum, but it had never really been conclusively detected due to how faint the signals are," Vernstrom said.

To search for the faint signals, the researchers used data from the Global Magneto-Ionic Medium Survey, the Planck Legacy Archive, the Owens Valley Long Wavelength Array and the Murchison Widefield Array to stack radio imaging from 612,025 galaxy cluster pairs, grouped together if they were close enough to be directly connected by cosmic web tendrils. This stacking helped boost the faint radio emissions from the shock waves beyond noisy background effects.

Then, by looking only for polarized radio waves — whose rays vibrate at the same angle as each other and were predicted in simulations to be emitted by the shock waves — the researchers found the signal.

"As very few sources emit polarised radio light, our search was less prone to contamination and we have been able to provide much stronger evidence that we are seeing emissions from the shock waves in the largest structures in the universe, which helps to confirm our models for the growth of this large-scale structure," Vernstrom said.

Now that the shock waves' existence has been confirmed, they could be used to probe the nature of the enormous magnetic fields that suffuse the web, which play an unknown role in shaping the universe.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus