Genes from 'culturally extinct' Indigenous group discovered in unsuspecting Tennessee man

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The last known members of the Indigenous Beothuk people of Newfoundland were thought to have died out 200 years ago. But genes from these people have been found in a man living in Tennessee today, researchers reported.

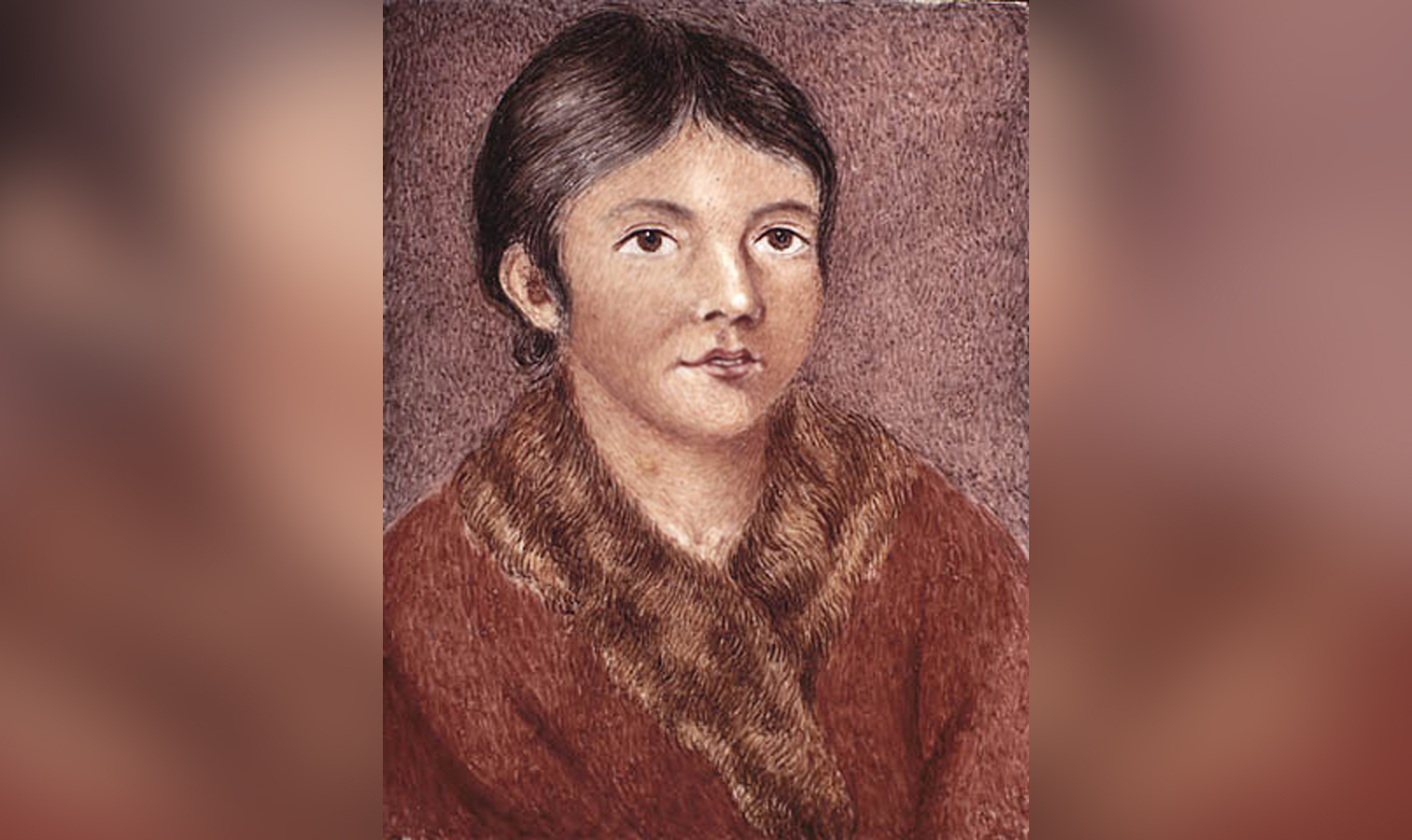

Shanawdithit, a Beothuk woman who died of tuberculosis in 1829, was the last known Beothuk. The group had thrived in Newfoundland with as many as 2,000 people there, until the Europeans arrived in the early 1500s, bringing disease and pushing the Beothuk inland, away from their traditional fishing and hunting grounds, which led to their starvation.

However, even though the Beothuk culture is extinct, their genes are not. The new genetic study found Beothuk genes identical to those of Shanawdithit's uncle in a Tennessee man. They also found fairly-well matched genetic sequences in members of the modern-day Ojibwe (also known as the Chippewa) people, said study researcher Steven Carr, a professor of biology at Memorial University in Newfoundland, with a cross-appointment in population genetics.

Related: 10 things we learned about the first Americans in 2018

The idea that the Beothuk live on isn't surprising to other Indigenous groups from the Newfoundland region. For instance, the oral traditions of the Miawpukek First Nation, the easternmost tribe of the Mi'kmaq people, a group whose history and geography overlap with that of the Beothuk, hold that Beothuk descendants have survived through the ages.

Carr conducted the study, in part, because "everybody wonders what happened to the Beothuk," he said. "There are people that claim descent from the Beothuk Indians," even though they don't have evidence to support such family ties. For instance, in 2017, a woman in North Carolina claimed to be of Beothuk descent after a commercial ancestry company, using incomplete data, mistakenly suggested this ancestry, according to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

New findings about an old culture

In an earlier study, published in 2017 in the journal Current Biology, researchers reported no close genetic relationship among three Indigenous groups in Newfoundland: the Maritime Archaic, who lived in Newfoundland from about 8,000 to 3,400 years ago before mysteriously disappearing; the Palaeoeskimo, who visited and then lived on Newfoundland from about 3,800 to 1,000 years ago, meaning that they overlapped with the Maritime Archaic and the Beothuk; and the Beothuk, who lived on Newfoundland from about 2,000 to 200 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, published April 13 in the journal Genome, Carr reanalyzed already published genetic data from the Beothuk. In a nutshell, he looked at mitochondrial DNA (genetic data passed down from mothers to children) taken from the archaeological remains of 18 Beothuk individuals and the skulls of Shanawdithit's aunt and uncle, Demasduit and Nonosabasut, respectively. (These skulls had been stolen in 1828 and sent to the University of Edinburgh, but were repatriated to Newfoundland in March after a long campaign by the Mi'kmaq and other Indigenous groups, according to The Guardian.)

Carr searched for matches to the Beothuk mitochondrial DNA in GenBank, a database run by the U.S. National Institutes of Health that is chock-full of DNA sequences from research projects done around the world, as well as from people who use commercial DNA testing.

The search showed that a Tennessee man had mitochondrial DNA matching Nonosabasut, Carr said. The man told Carr he had traced his mother's side of the family five generations back, and he was surprised about his link to the Beothuk, as he wasn't aware of any such relation in his genealogy tree.

"He's now extremely intrigued and will continue looking for that [link]," Carr said.

Just like in the Current Biology study, Carr found that the Maritime Archaic were not closely related to the Beothuk. However, the two groups do share a very distant ancestor; the oldest known Maritime Archaic individual — who died at about the age of 12 in southern Labrador about 8,000 years ago, according to an analysis of the burial — has DNA that is similar to the historic Beothuk, said William Fitzhugh, director of the Arctic Studies Center at the Smithsonian Institution, who was not involved with either study.

That's likely because the common ancestor of Indigenous Northeastern North America (except for the Innu and Innuit) date to at least 15,000 years ago, and the different groups that spread across this region likely descended from this ancestor, Carr said. However, the relationship between the Maritime Archaic and the Beothuk is distant, unlike the extremely close relation Carr found between the Beothuk and the Tennessee man.

Related: In images: An ancient long-headed woman reconstructed

The GenBank search also showed that the Beothuk and the ancient Maritime Archaic peoples from Newfoundland "both share ancestry with modern Canadian Ojibwe, meaning their genes can be traced back to ancestral Indian peoples in more geographically central regions [of Canada]," Fitzhugh told Live Science in an email.

However, the new study is limited by its sample size, Fitzhugh noted.

"One of my reactions is how complicated these DNA studies are and how dependent they are on available samples; that the technology of genomic analysis is relatively new and evolving rapidly, perhaps leading to different results," Fitzhugh said.

Next steps

In an earlier study, another group of researchers looked for genetic links between the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq. But this 2007 study, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, looked at very short pieces of DNA, so the results were largely inconclusive, Carr said.

Despite these results, Carr's work in genetics put him on the radar of Chief Mi'sel Joe of the Mi'kmaq First Nation. "The chief was interested in just having it demonstrated what they believed to be true," Carr said — that the Mi'kmaq and the Beothuk had pursued "family relations" with one another before the Beothuk went culturally extinct, Joe told Live Science.

There is only one Mi'kmaq in GenBank, so next Carr plans to work with Mi'kmaq First Nation to determine whether the Beothuk and Mi'kmaq are closely related, he said. This new study will include at least 200 or more registered Mi'kmaq (also spelled Mig'maw) people, so it will be larger than the 2017 study, he noted. (Carr added that he is serving as the study's principal investigator and advisor to the Mi'kmaq in a private capacity, through his company Terra Nova Genomics. This project is being funded through a National Geographic Explorer grant to Mi'kmaq First Nation.)

The results from this study may help detail the historic relationship between the Beothuk and Mi'kmaq people.

"We shared the same island [of Newfoundland] and the island really is not that big," Joe said. "Of course, from time to time, our people would encounter them and sometimes live with them," Joe said. "It wasn't always friendly," because of rivalries, but other times it was, he said.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to fix Steven Carr's title and to note that the oral traditions mentioned in this story are from the Miawpukek First Nation, the easternmost tribe of the Mi'kmaq people. The update also included that the "inconclusive" findings on the relationships between the Beothuk and Mi'kmaq were from a 2007, not a 2017 study.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus