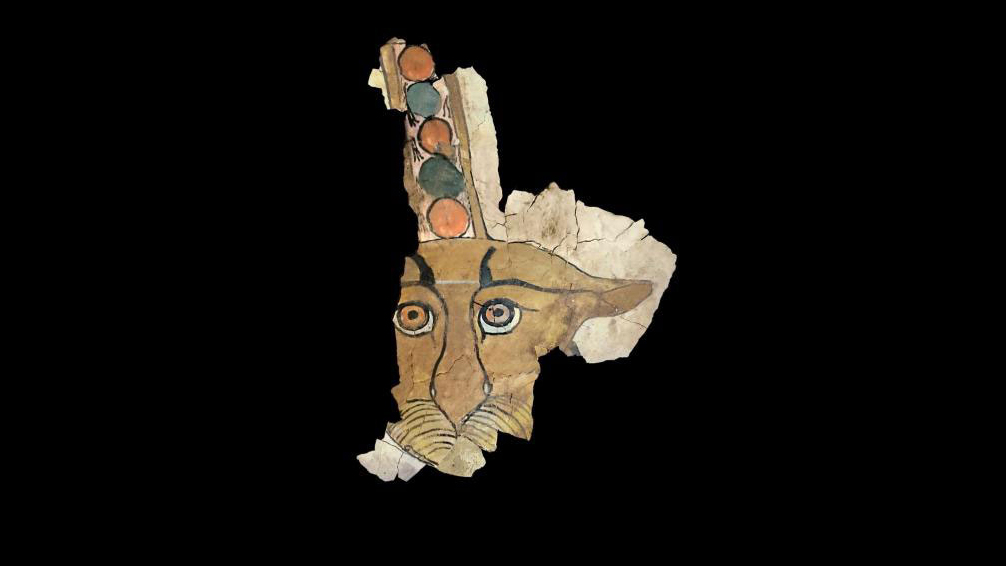

Hello kitty! Leopard face reconstructed from ancient Egyptian sarcophagus

Archaeologists discovered the painting in a network of tombs in Aswan, Egypt.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Excavation of an ancient city of the dead in Aswan, Egypt, recently uncovered pieces of a sarcophagus lid that had been decorated with the colorful face of a leopard. Now, archaeologists have released the first image showing a digital reconstruction of the artwork fragment, found in a necropolis containing 300 tombs and dating to the seventh century B.C.

In the image, most of the big cat's wide-eyed face is visible. When the lid rested on the sarcophagus, the head of the leopard would have aligned with the head of the mummy inside, representatives of the University of Milan said in a statement.

In ancient Egyptian society, leopards represented determination and power; the animal's representation in the tomb was likely intended to strengthen the spirit of the recently deceased for the journey to the land of the dead, according to the statement.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

The necropolis that housed the leopard sarcophagus was in use for approximately 1,000 years — until the fourth century A.D. — and the excavation was carried out by an international team of experts with the Egyptian-Italian Mission at West Aswan, according to a statement published in April 2019.

Other tombs held a total of 35 mummies and a number of funerary objects, such as pots of bitumen for mummification, linen and papyrus funeral masks, and food offerings for the trip to the afterlife.

"We made the discovery at the end of January 2019, but just finished the 'virtual' restoration of the fragment," Patrizia Piacentini, director of the excavation for the Egyptian-Italian Mission at West Aswan, told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A nearby tomb held another extraordinary find: a bowl holding plant material that turned out to be pine nuts. Though the nuts were not native to the region, they were known to have been used by chefs in Alexandria, according to a Roman cookbook called "Apicius" that was compiled in the first century A.D., university representatives said in the February statement.

One recipe described soft-boiled eggs in a sauce made with pine nuts, ground pepper, honey and anchovy paste, according to a translation that appeared in the book "Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome" (The University of Chicago Press Books, 2005).

As for why the pine nuts were left in the necropolis, "We like to imagine that the people buried in the tomb of Aswan loved this rare seed — so much so that their relatives placed a bowl next to the deceased that contained them, so that they could feed on them for eternity," Piacentini said in the February statement.

- Photos: The amazing mummies of Peru and Egypt

- Photos: 4,400-year-old tomb complex in Egypt

- Photos: Discoveries at Wadi el-Hudi, an ancient Egyptian settlement

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus