The closest black hole to Earth is no more — in fact, it never existed

Astronomers fell for a cosmic optical illusion — but the truth may be just as cool.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 2020, astronomers identified a nearby star system that appeared to contain something phenomenal: the closest black hole to Earth, sitting a mere 1,000 light-years away (that's less than 1% of the width of the Milky Way). Now, new research from some of those same astronomers suggests that they may have been deceived by a cosmic illusion.

In a new study published March 2 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, researchers took another look at that star system — named HR 6819 — with the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope. What appeared in 2020 to be a system of three massive objects — a large star orbiting a black hole every 40 days, with a second star orbiting much farther away — actually contains no black hole at all, the researchers wrote.

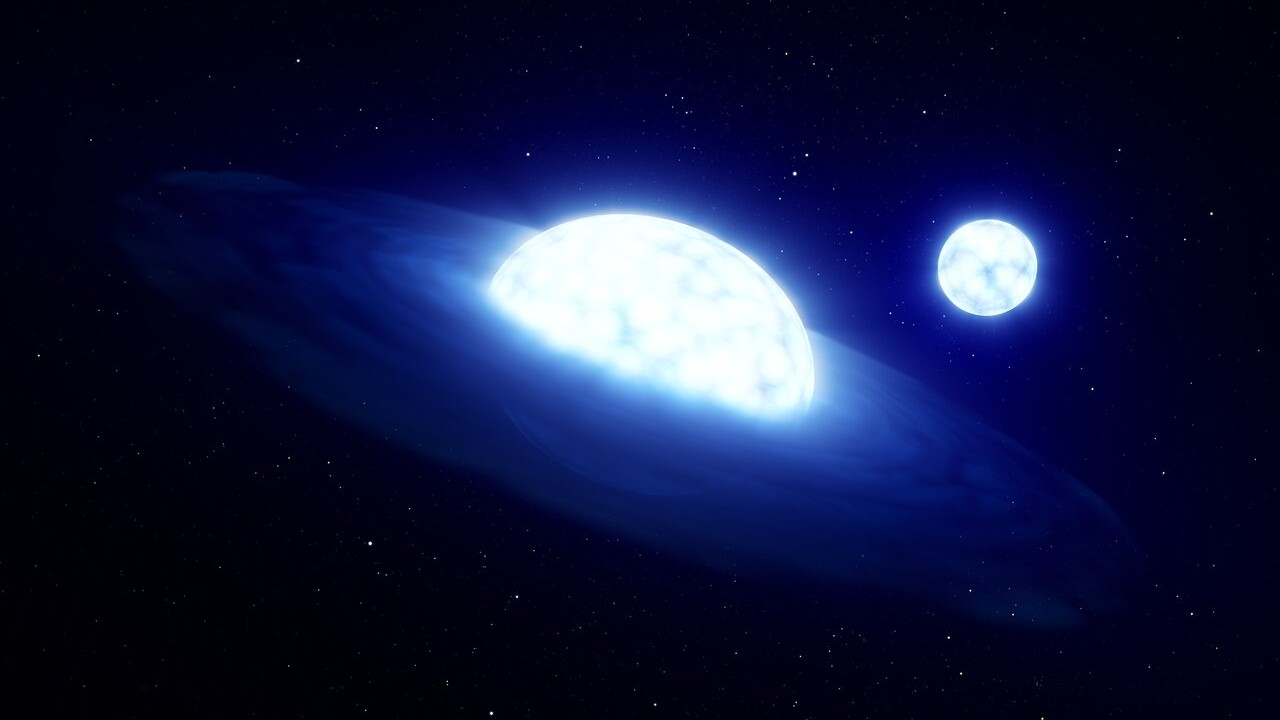

Instead, HR 6819 now appears to be a system of just two stars orbiting each other very closely, and with a very fraught relationship.

Related: 15 unforgettable images of stars

"Our best interpretation so far is that we caught this binary system in a moment shortly after one of the stars had sucked the atmosphere off its companion star," study co-author Julia Bodensteiner, an ESO Fellow in Munich, Germany, said in a statement. "This is a common phenomenon in close binary systems, sometimes referred to as stellar vampirism."

As a result, one star lost a tremendous amount of its mass to the other star around the time astronomers observed them in 2020 — making it appear as though the two stars were orbiting each other very far apart, when in fact one star was just much larger than the other, the researchers said. This vampiric mass transfer also would have made the recipient star spin more rapidly, further amplifying the illusion that it was much closer to Earth than its smaller companion star. No black hole required.

Bodensteiner and her colleagues originally proposed this vampire star hypothesis in a June 2020 paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics — one month after the publication of the paper claiming that HR 6819 contained the closest black hole to Earth. In the new paper, Bodensteiner and the authors of the original HR 6819 study joined forces to find out, once and for all, which one of them had the better theory about the strange star system's behavior.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using several of the Very Large Telescope's high-definition instruments, the researchers found that the two stars in HR 6819 actually orbit one another at only one-third of the distance between Earth and the sun — meaning one of them was much larger and faster-spinning than the other. The vampire star hypothesis won out.

So, while Earth's nearest known black hole may have just been pushed back a few thousand light-years (the next closest one sits about 3,000 light-years away, Live Science previously reported), HR 6819 remains an intriguing study target for other reasons entirely.

"Catching such a post-[vampirism] phase is extremely difficult as it is so short," lead study author Abigail Frost, a postdoctoral researcher at KU Leuven in Belgium, said in the statement. "This makes our findings for HR 6819 very exciting, as it presents a perfect candidate to study how this vampirism affects the evolution of massive stars."

Meanwhile, the search for nearby black holes continues undaunted. According to the study authors, there are tens of millions to hundreds of millions of black holes lurking in the Milky Way alone. It's only a matter of time before astronomers stumble upon another one in our cosmic backyard.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus