Syphilis originated in the Americas, ancient DNA shows, but European colonialism spread it widely

Paleogenomics has finally solved a question that has puzzled researchers for decades: Where did syphilis come from?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The outbreak of a mysterious disease ravaged Europe in the late 15th century, shortly after Christopher Columbus and his crew returned from the Americas. Experts have debated for centuries where this malady — now known as syphilis — originated. Now, new research into ancient genomes has finally provided an answer: It turns out, syphilis came from the Americas, not Europe.

"The data clearly support a root in the Americas for syphilis and its known relatives," study co-author Kirsten Bos, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, said in a statement. "Their introduction to Europe starting in the late 15th century is most consistent with the data."

The researchers analyzed human skeletons from numerous archaeological sites in the Americas for evidence of syphilis and related diseases. They revealed their findings in a study published Dec. 18 in the journal Nature.

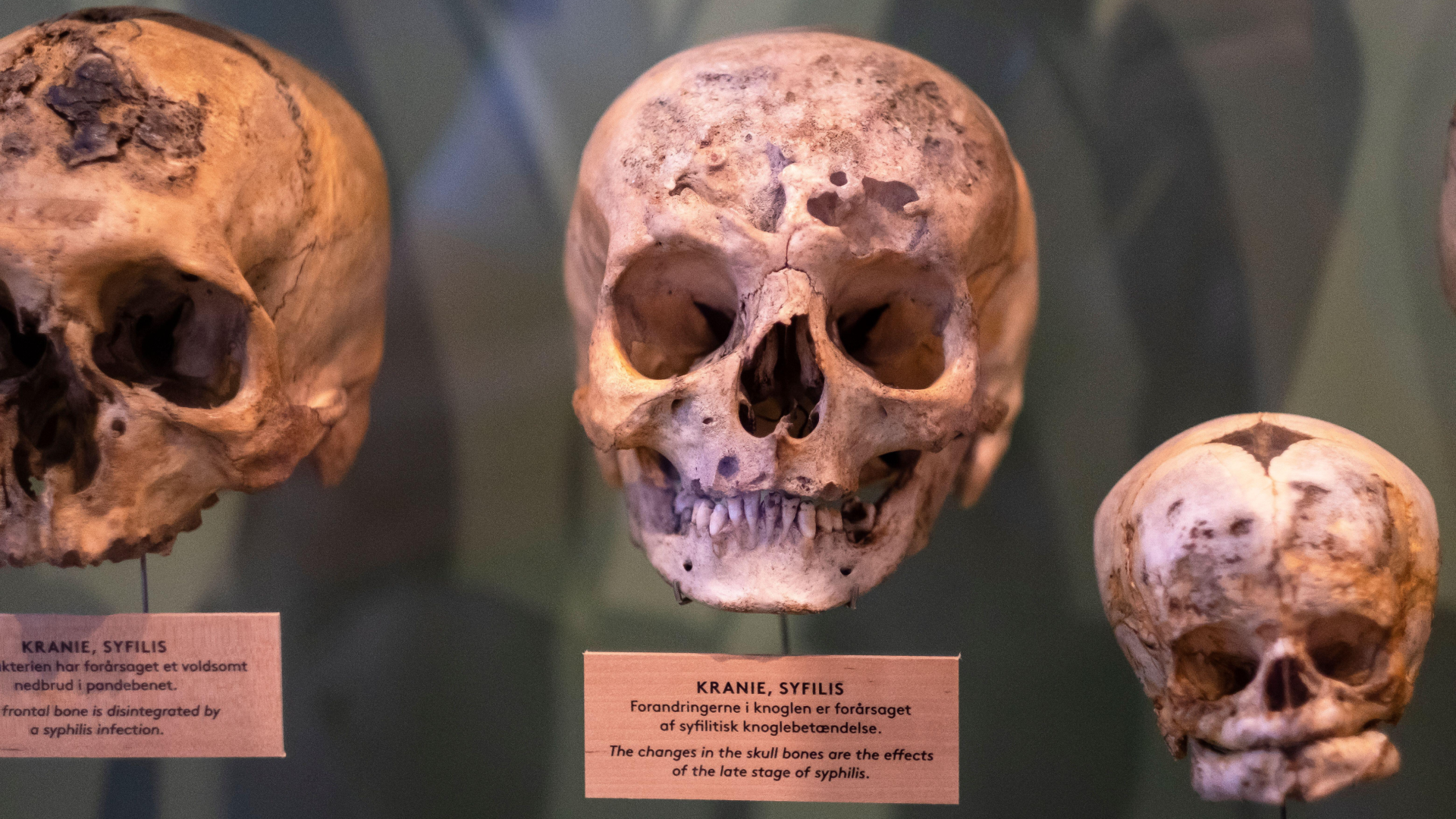

Bacteria in the genus Treponema cause the non-venereal diseases pinta, bejel and yaws in addition to venereal syphilis, and these are collectively known as treponemal diseases. All of these diseases can cause the destruction and remodeling of bone during a person's life, so archaeologists have long investigated pre-Columbian skeletons in the Americas for clues to the origin of syphilis.

But clear genetic evidence of syphilis has been more difficult to find because of the poor preservation of treponemal DNA over the centuries.

Related: 9 of the most 'genetically isolated' human populations in the world

"We've known for some time that syphilis-like infections occurred in the Americas for millennia, but from the lesions alone it's impossible to fully characterize the disease," study co-author Casey Kirkpatrick, a postdoctoral researcher at Max Planck, said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the researchers took samples from the teeth and bones of dozens of skeletons from the Americas that showed signs of a treponemal infection. Then, thanks to advances in genomic technology, they were able to isolate Treponema pallidum genomes from the skeletons of five people who died in what are now Mexico, Peru, Argentina and Chile before 1492.

Based on their genomic analysis, the researchers found that T. pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis and related diseases, originated in the Americas during the middle Holocene epoch, as far back as 9,000 years ago, and then split off into the subspecies that cause the various treponemal diseases.

But modern syphilis may have cropped up just before the arrival of Columbus, the scientists wrote in the study, and rapidly expanded in the early colonial period corresponding with the rise in transatlantic human trafficking.

"While indigenous American groups harboured early forms of these diseases, Europeans were instrumental in spreading them around the world," Bos said in the statement.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus