Nearly 400 ancient medical tools from Turkey hint at rare Roman doctors' offices

Medical instruments dating to the Roman era may be evidence of a "group practice" run by health care workers.

Hundreds of Roman-era medical instruments now being examined by scientists may come from one of the earliest known examples of a group medical practice, or at least a place where health care workers congregated to treat people.

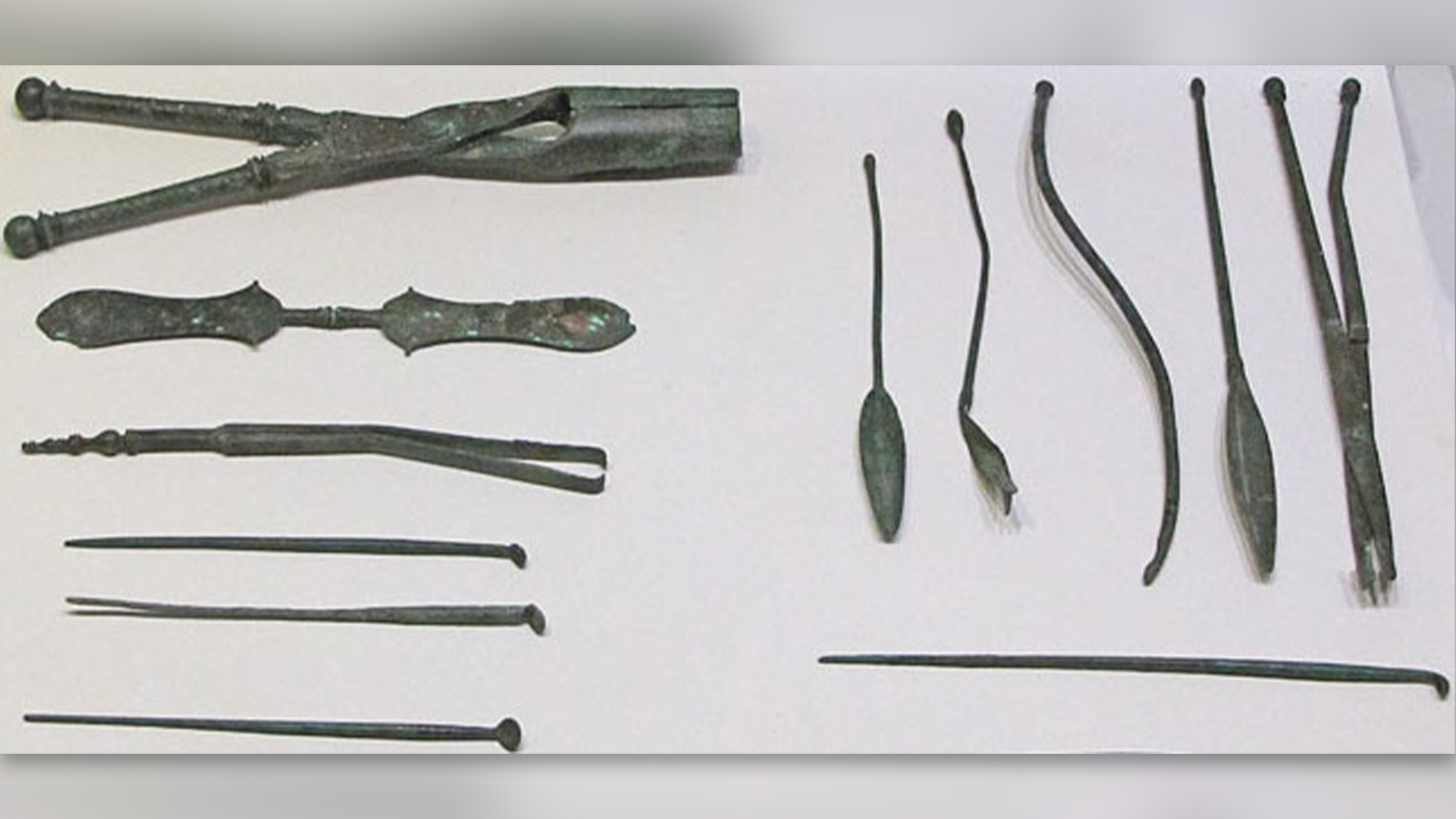

A total of 348 artifacts linked to medicine were found at the site of Allianoi, an ancient town that also hosted a large spa-like bath in what is now Turkey. The vast number of the 1,800-year-old artifacts may indicate the site once featured an ancient medical center. The instruments were discovered during rescue excavations that were carried out between 1998 and 2006, before the construction of a dam that flooded the site. Most of the artifacts, which have been studied over the years, were found within two buildings in a larger complex.

"Allianoi was, perhaps, one of the earliest known cases of an organized, group medical practice," Sarah Yeomans, an archaeologist at St. Mary's College of Maryland, wrote in the abstract of a paper she presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Classical Studies, which ran from Jan. 4 to 7 in Chicago.

"The categories and variety of surgical instruments indicate that relatively sophisticated surgical procedures were undertaken at Allianoi," Yeomans wrote. These include instruments used to remove hemorrhoids, as well as tools to extract bladder and kidney stones. Other instruments indicate that cataract surgery, or the removal of a person's cloudy eye lens, and the suturing of wounds may also have taken place at the center.

The researchers don't know how many medical practitioners worked at the site at any one time, "though it was likely dozens or more, depending on the time period," Yeomans told Live Science in an email.

Related: 1st-century burial holds Roman doctor buried with medical tools, including 'top-quality' scalpels

However, while these health care workers may have gathered in the same spot, that doesn't mean they were colleagues.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Please keep in mind that this wasn't an organized 'practice' in the sense that they were all working for a single business, like today," Yeomans said. "Rather, it would have been more like Harley Street in London in the 19th century where all sorts of practitioners or specialists set up shop in the same location."

Daniş Baykan, an archaeology professor at Trakya University in Turkey who was not involved with the new research but completed his doctoral thesis on Allianoi, told Live Science in an email that he had previously made similar findings. Baykan also found that the instruments were used for a variety of procedures. He suggested that the ancient doctor Galen, who lived from around A.D. 129 to 216 and resided in nearby Pergamon, may have practiced at Allianoi.

Ancient records indicate that Galen successfully performed surgeries on injured gladiators, and he may have undertaken these at Allianoi, Baykan suggested.

Patty Baker, a senior lecturer of classical and archaeological studies at the University of Kent in the U.K. who was also not involved with the new research, said it is not surprising that the facility was located near a bath. In the Roman world, "a lot of medical tools are found in bath buildings because they were places people would go for health care," Baker told Live Science in an email.

Baker added that while it's possible that a group of physicians worked at the site, we can't say for certain based on the current evidence.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus