Painted saddle found in Mongolian tomb is oldest of its kind

A fifth century Mongolian saddle is one of the earliest examples of evidence of modern horse riding.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A wooden frame saddle with iron stirrups that was stunningly preserved in an ancient tomb in Mongolia may be the oldest of its kind. The innovative saddle could give archaeologists clues to the origins of medieval mounted warfare.

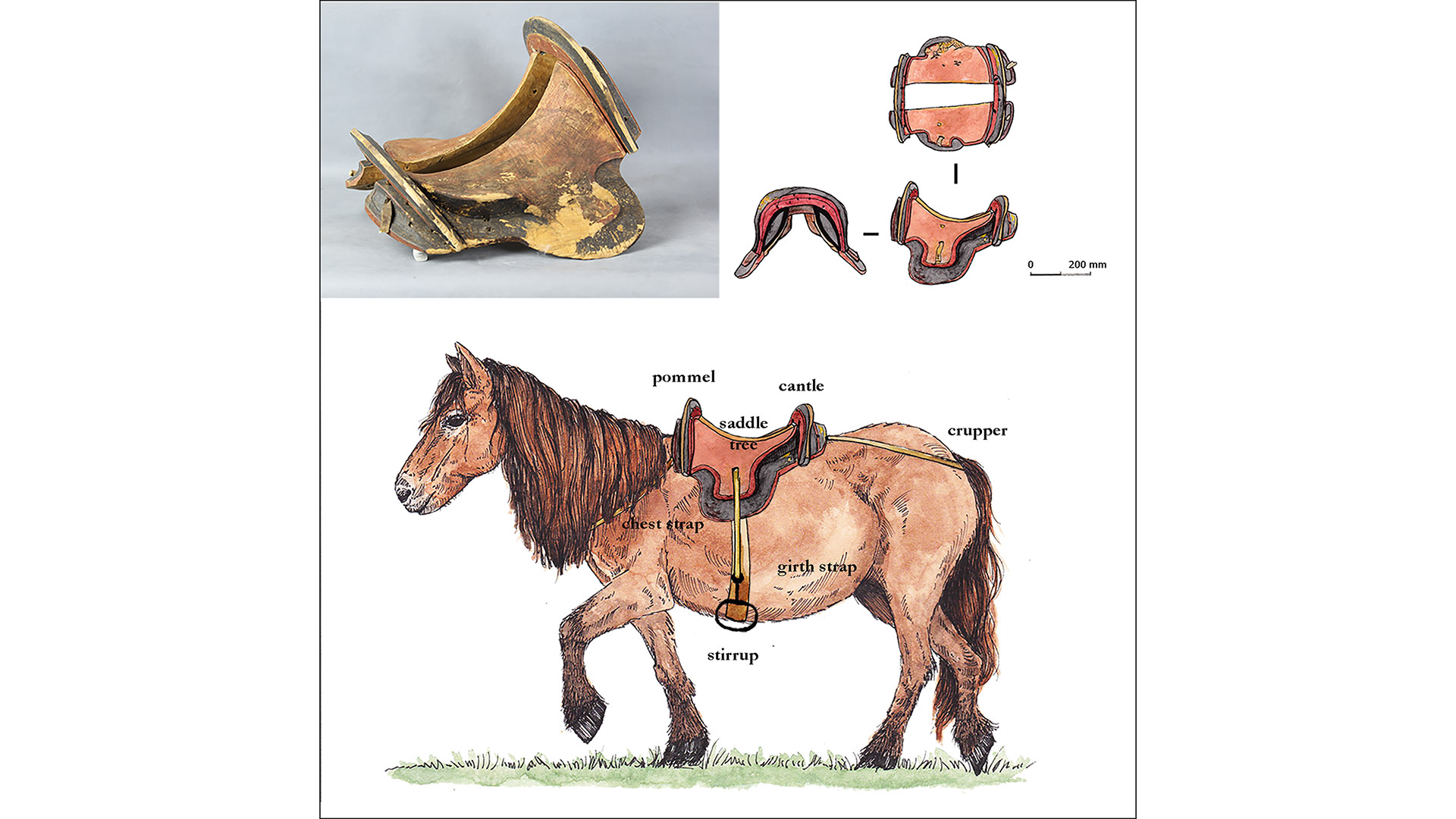

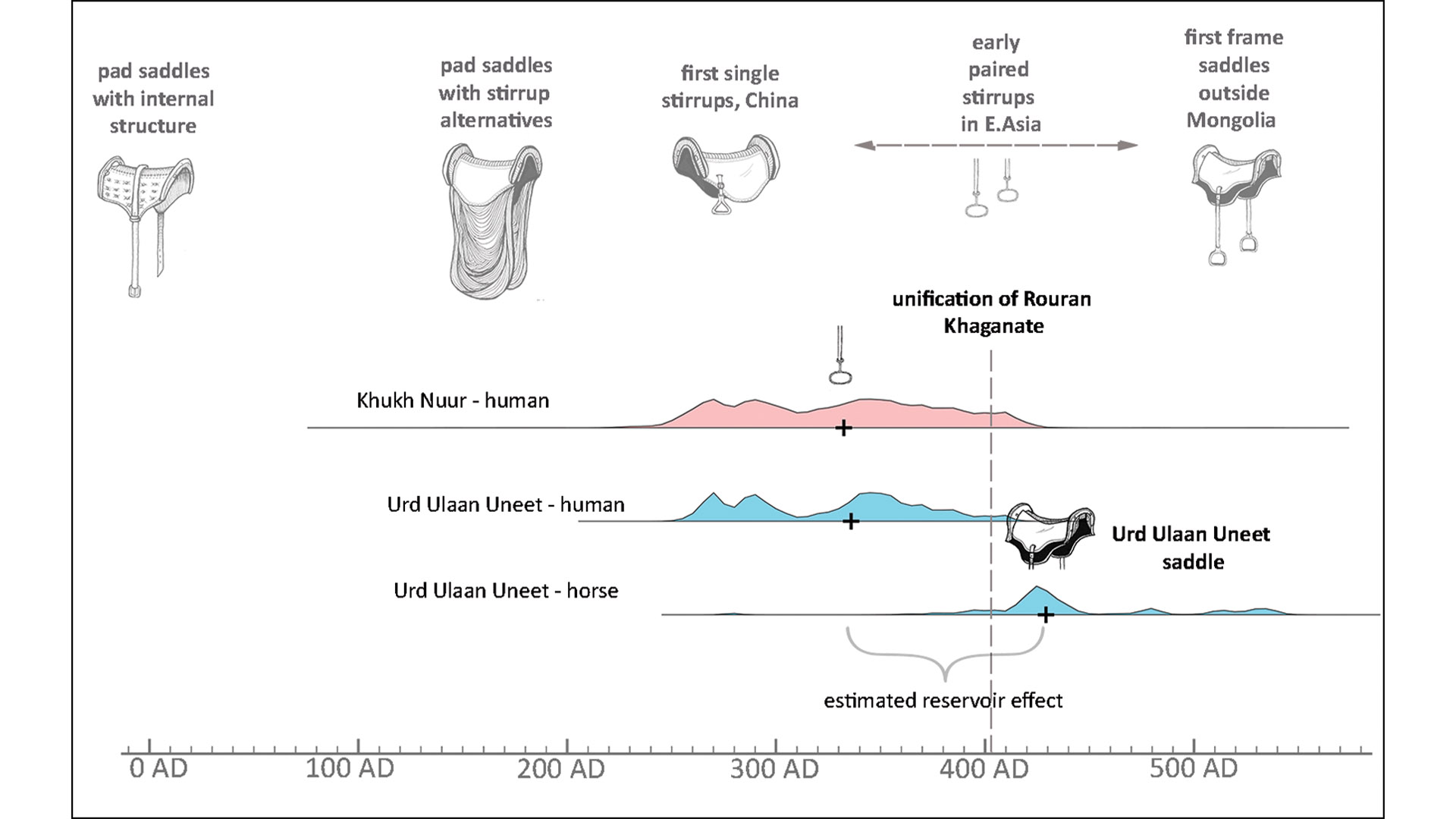

In a study published today (Dec. 8) in the journal Antiquity, an international team of archaeologists described the painted saddle, which was previously looted from a cave burial. Radiocarbon dating of the human remains in the tomb and a sample of the horsehide saddle indicate it dates to around 420 A.D., making it the oldest known frame saddle in the world.

"Our study raises the possibility that the Eastern Steppe played a key role in the early development and spread of the frame saddle and stirrup," the researchers wrote in their paper.

Modern horses were first domesticated around 2000 B.C. in Western and Central Asia, and nomadic riders quickly used them to support their mobile lifestyle. Early equestrianism was essentially bareback, as riders armed with bows and arrows gripped the horse with their legs while holding onto the horse’s mane, the researchers noted. Within a few centuries, people roaming the northern steppes invented the bridle and bit, and they shifted to mounted riding on a soft pad around 1000 B.C.

But rigid saddles complete with stirrups — an important part of cavalry equipment — are a much more recent invention. Direct evidence for when they originated has eluded archaeologists because organic material does not always preserve well in the harsh climate of the steppe.

In 2015, police notified archaeologists at the National Museum of Mongolia that a cave burial at Urd Ulaan Uneet, near the province of Khovd in the western part of the country, had been looted. The police confiscated several artifacts, including a birch saddle painted black and red with leather straps on either side, an iron bit, wooden archery equipment and mummified horse remains. They also took possession of the bones of a man who was buried wearing sheep- and badger-hide clothing. The tomb quickly became known as the "cave of the equestrian."

In the new study, the researchers discovered through DNA testing that the human remains were those of a man and that the animal was a male domestic horse. Radiocarbon dating of the human remains and the leather stirrup strap from the saddle placed the burial and the saddle around 420 A.D.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our study raises the possibility that the Eastern Steppe played a key role in the early development and spread of the frame saddle and stirrup," the researchers wrote in their paper. Study author William Taylor, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, told Live Science in an email that "developing a rigid frame that could support a suspended stirrup was a watershed moment, really unlocking a whole host of other things people could do while mounted." For example, a rider could use them for stability and standing up, freeing up the rider's upper body for delivering blows while on the horse and giving them a major advantage in mounted warfare.

The new information the researchers found in their study shows that horse cultures of the Eurasian steppe were early adopters of frame saddles and stirrups, further suggesting that "Mongolian steppe cultures were closely tied to key innovations in equestrianism, an advance that had a major impact on the conduct of medieval warfare."

But domestication was hard on the horses. The horse found in the Urd Ulaan Uneet burial had bit-related damage to his teeth and changes to his nasal bones, similar to injuries found in other horse burials in Central and Eastern Asia. Additionally, the Urd Ulaan Uneet horse had "healed nock marks to the ears that might have been used to show who the horse belonged to during its life," Taylor said.

Although the "cave of the equestrian" housed a man, horse riding wasn't just for men, Taylor said. "There's every reason to think that both men and women were regularly riding horses since the earliest appearance of horses in the Eastern Steppe," he said.

Future work is needed, particularly in areas of East Asia with exceptional organic preservation, to help clarify whether wooden frame saddles were invented in the Eastern Steppes, the researchers said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus