Live Science has always been on top of breaking news. But we've recently started taking a deeper look at topics our readers love. So was born our news features, which you'll find nowhere else.

One of my favorite of these stories is actually a retelling of one we all learned in middle school — that the first Americans crossed the Bering Land Bridge about 13,000 years ago, flanked by massive ice walls on either side.

But while the broader picture of that incredible journey still holds, our understanding is being dramatically reshaped by the discovery of older archaeological sites and genetic analyses of ancient fossils and modern populations. Our archaeology editor, Laura Geggel, has covered the history of the Americas extensively, and when we first assigned the story we weren't sure how much new there would be to report. How wrong we were.

While digging into the continent's history, she learned that fossil footprints from White Sands, New Mexico date to about 23,000 years ago. Yet several lines of genetic evidence suggest people came a few thousand years later. Resolving this contradiction is going to be tricky.

Hopefully, in the coming years new archaeological sites will emerge — possibly along the submerged coast of British Columbia — that will help us reconcile the genetic evidence and the archaeological record.

As Laura says, "this story is far from finished."

The untold story of the first Americans

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

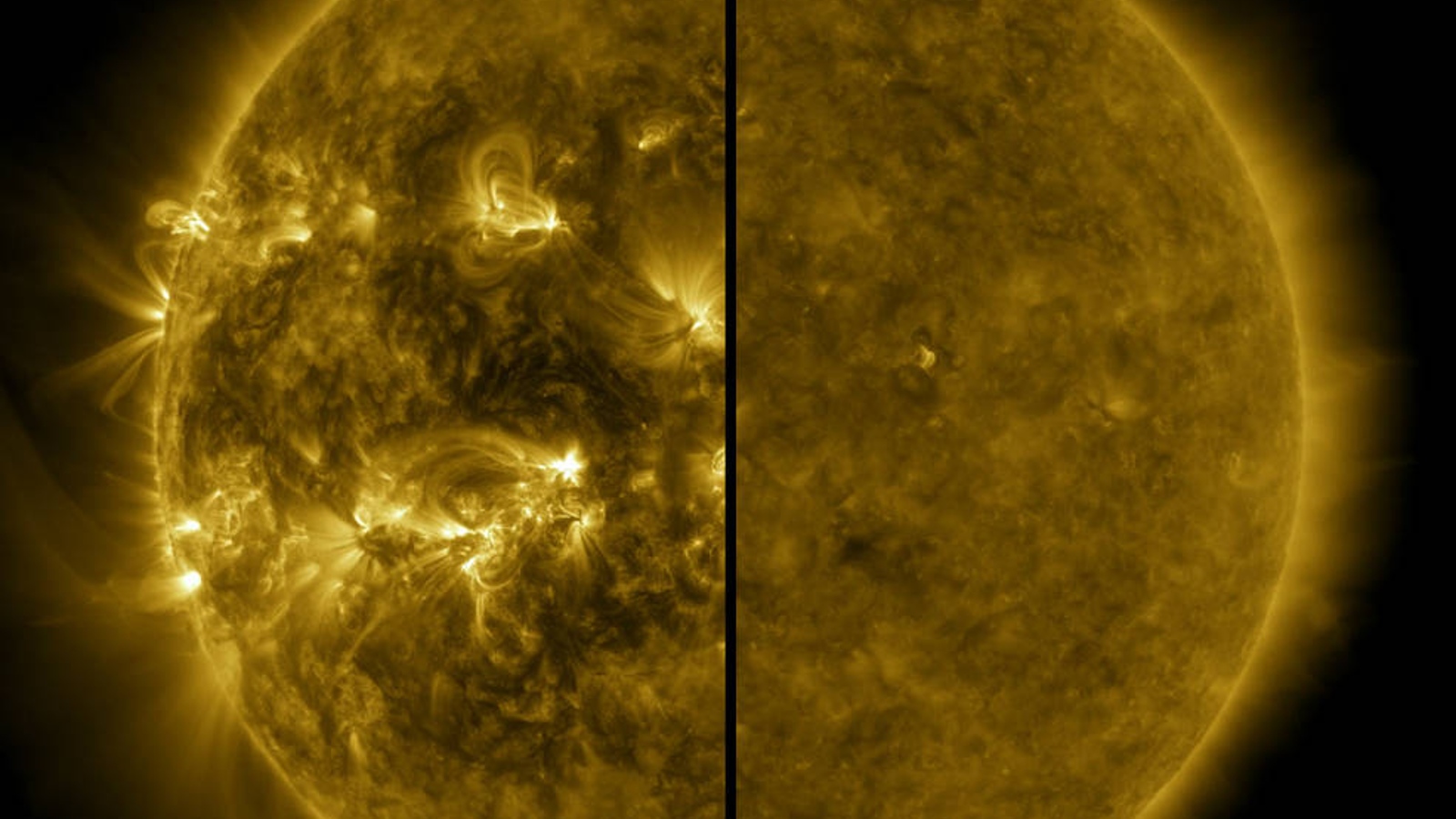

Our home star spits out solar storms in a waxing and waning pattern known as the 11-year solar cycle. NASA and NOAA initially predicted the sun would reach its peak, or solar maximum, sometime in 2025. But senior writer Harry Baker was covering each solar temper tantrum individually and noticed an uptick in activity. Then, a source at the National Center for Atmospheric research said their models showed an earlier and stronger solar maximum than NASA. Harry broke the story in June, and in October, scientists revised their solar maximum estimate..

The sun's explosive peak is coming. Are we ready?

In May, orcas rammed three boats off the Iberian peninsula. From her reporting, trainee staff writer Sascha Pare knew a pair of serial killer whales off South Africa were slaughtering sharks and eating their livers and that orcas were also taking down Earth's biggest creatures — blue whales. Then a source told her that off Washington, orcas had been playing with porpoises to death, a macabre game that must have had a "higher purpose," Sascha said, because they weren't eating the poor harassed things.

But what was that higher purpose: killing for fun, training, revenge, or boredom?

And stay tuned in 2024. We'll be diving into the Earth to study the births and deaths of supercontinents, zooming into the subatomic realm, where "quantum superchemistry" speeds up chemical reactions by billions of times, and traveling along with the minimoons that are our Earth's companions — and potential stepping stones for future space missions.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus