Cup crafted from prehistoric human skull discovered in cave in Spain

A new study suggests that Spain's ancient peoples shared complex beliefs about death and the afterlife.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient human bones buried thousands of years ago in a cave in southern Spain show signs of being manipulated — and perhaps even eaten in possible bouts of cannibalism, according to a new study.

The finds include a human shinbone used as a tool and a drinking cup crafted from a human skull. Similar evidence is found all over the region, hinting that the relationship between the living and the dead was fundamental to human societies at that time, the researchers reported in the study, published Wednesday (Sept. 20) in the journal PLOS One.

"The ways in which humans treat and interact with [human] remains can teach us about the cultural and social aspect of past populations," including their manipulation, retrieval and reburial, the researchers said in a statement.

Authors Zita Laffranchi and Marco Milella, both bioarchaeologists at the University of Bern in Switzerland, and Rafael Martínez Sánchez, an archaeologist at the University of Córdoba in Spain, studied human remains from at least 12 ancient burials from Mármoles cave, about 45 miles (70 kilometers) southeast of Córdoba. The cave was occupied by prehistoric humans at different times, and several ancient burials have been excavated there since the 1930s.

Related: 7,000-year-old mass grave in Slovakia may hold human sacrifice victims

Most of the burials in the new study were excavated between 1998 and 2018. The researchers identified the remains of seven adults and five children or juveniles, who'd been interred between the fifth and second millennium B.C. — roughly from the region's Neolithic period to its Bronze Age.

Broken bones

Microscopic analysis of the bones in the new study found that many showed signs of being deliberately fractured, perhaps to consume their marrow, and scraped to remove any flesh.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

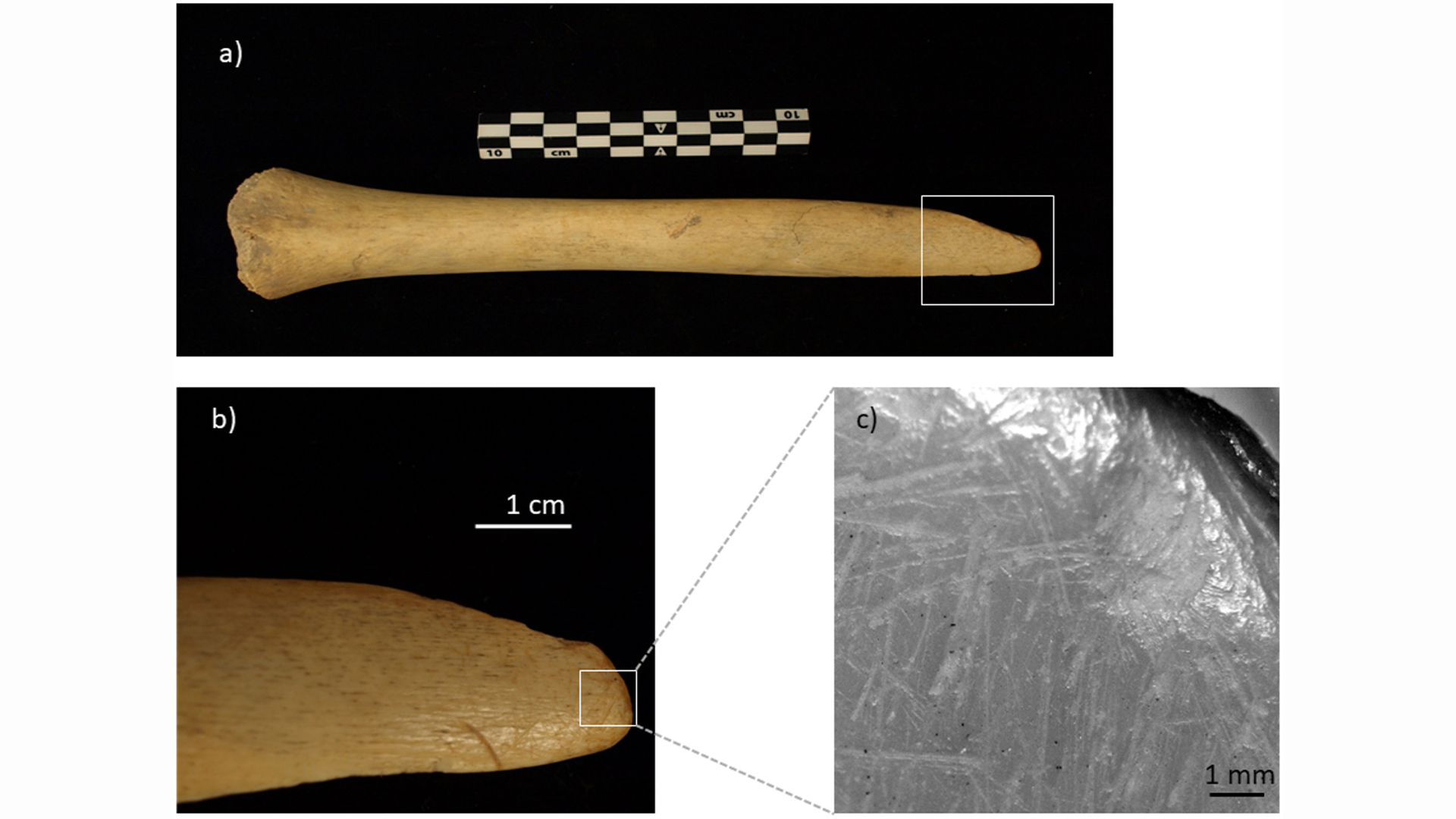

The team also found a human shinbone, or tibia. Based on the polish and pits on parts of the bone, it seems to have been used as some sort of primitive tool, although the authors didn't speculate on its function.

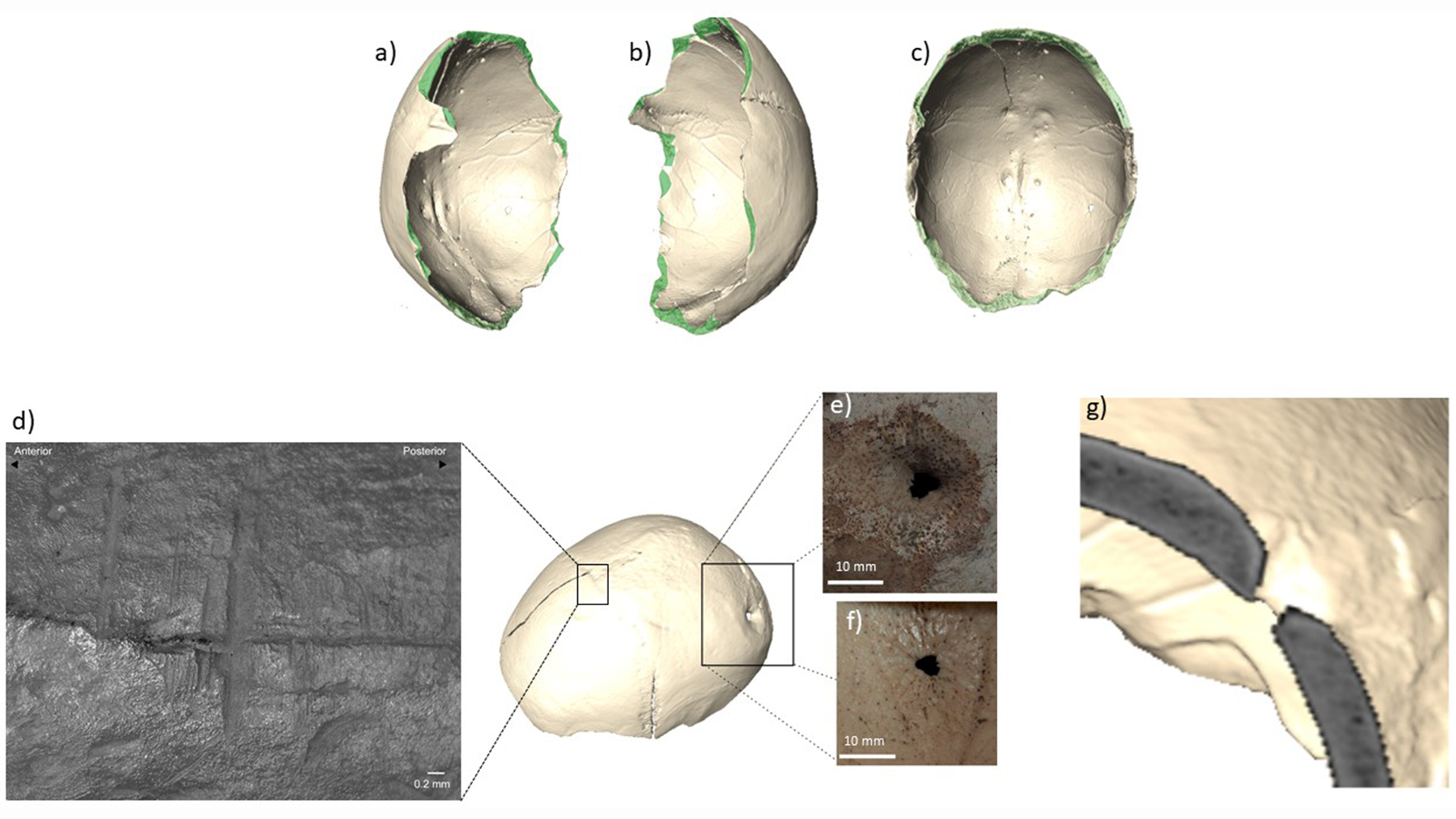

Perhaps the most striking object they studied was a "skull cup" made from a human cranium, probably from a man between the ages of 35 and 50 when he died.

The analysis showed ancient people had intentionally separated the cranium from the lower skull by fracturing the bone at its edges, and then repeatedly scraped it to remove any flesh.

Similar "skull cups" have been found at several other Neolithic sites in southern Spain, the authors said. Although they might have been attempts to access the brain so it could be eaten, some skulls have marks consistent with their later use, perhaps as drinking vessels.

Life and death

The researchers said they can't tell exactly how or why many of the human remains in the Mármoles Cave were utilized after death, but they suggested that some of the bones were broken to extract marrow, a valuable source of nutrients, while others may have been modified into tools or weapons or used for rituals.

There's evidence of similar manipulations from other cave burials across southern Iberia at that time, indicating that these ancient societies shared complex cultural beliefs about death and the afterlife, the authors said.

Natural processes in caves could sometimes damage bones without any human intervention, "but the data suggest some targeted practices here," said archaeologist Christian Meyer, head of the OsteoArchaeological Research Centre in Goslar, Germany. Meyer wasn't involved in the new study, but he has published widely on enigmatic Neolithic burial sites.

One question was whether the people who reused the bones always recognized if they came from other humans — an issue the authors had rightly discussed, he said.

"For sites like these, with multi-period, episodic funerary use and occupation, definite answers to complex questions are almost impossible to get," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus