Long-lost branch of the Nile was 'indispensable for building the pyramids,' research shows

The Nile's now-extinct branch likely helped the ancient Egyptians move materials to pyramid building sites.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

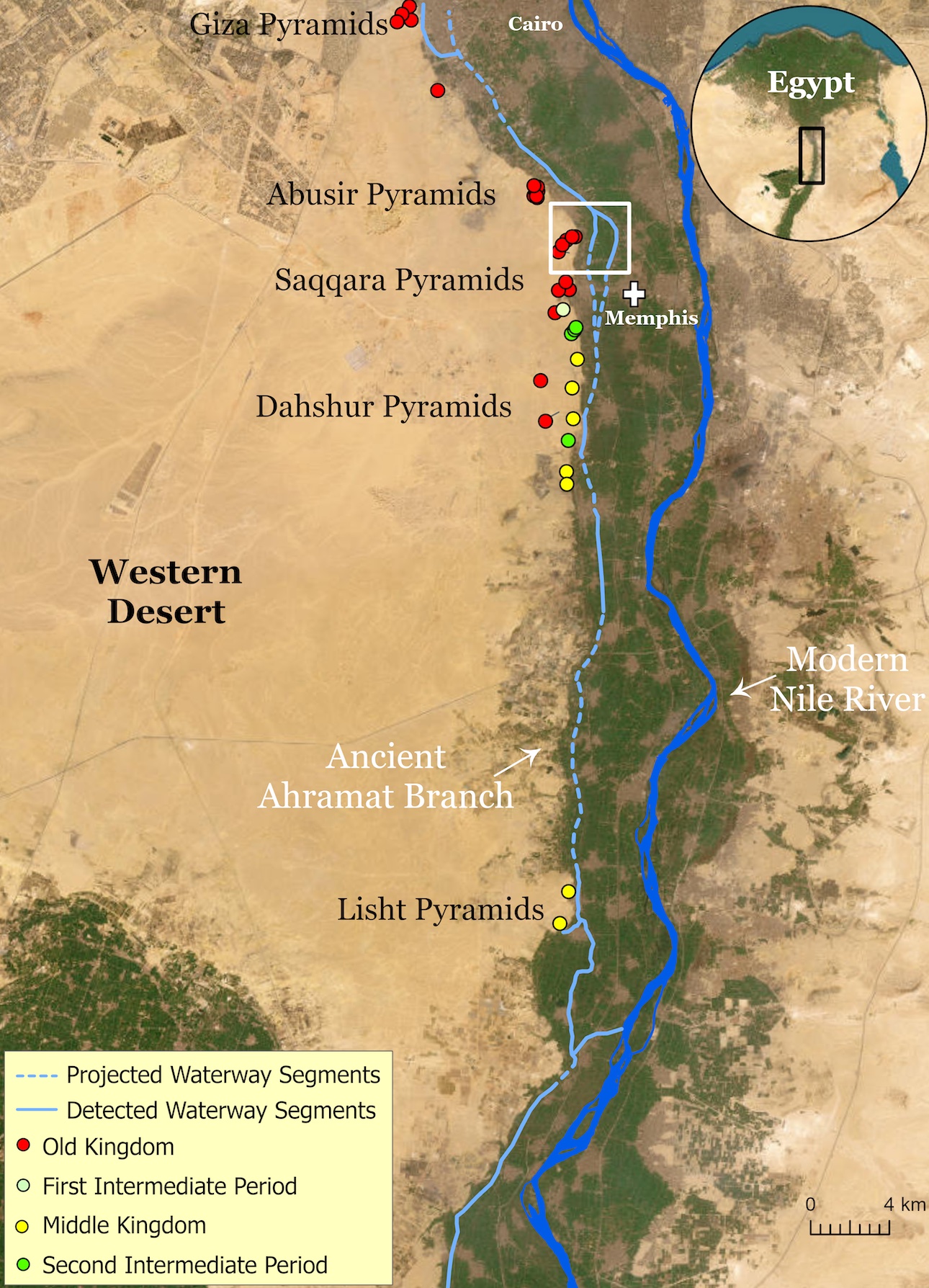

A branch of the Nile that no longer exists helped the ancient Egyptians construct 31 of their famous pyramids, including the pyramids at Giza, a new study finds.

Researchers found that this branch, called the "Ahramat" (Arabic for "pyramid"), was about 40 miles (64 kilometers) long and went close to the sites of many pyramids, making it easier to transport materials.

"Many of the pyramids, dating to the Old and Middle Kingdoms, have causeways that lead to the branch and terminate with valley temples which may have acted as river harbors," study first author Eman Ghoneim, a professor and director of the Space and Drone Remote Sensing Lab at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, told Live Science in an email.

The team used radar satellite imagery, deep soil coring and geophysical tests to find and map the remains of the Ahramat branch.

"The enormity of this branch and its proximity to the pyramid complexes, in addition to the fact that the pyramids' causeways terminate at its riverbank, all imply that this branch was active and operational during the construction phase of these pyramids," Ghoneim and colleagues wrote in the study, published Thursday (May 16) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Related: How old are the Egyptian pyramids?

The team found that the Ahramat branch shifted eastward as time went on. The Ahramat Branch was positioned further west during the Old Kingdom (circa 2649 to 2150 B.C.) and then shifted east during the Middle Kingdom (circa 2030 to 1640 B.C.), the team wrote in their paper.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eventually, the branch dried up. "There is no exact date on when the branch come[s] to an end," Ghoneim said. But as drought condition intensified in the region, the water level of the Ahramat Branch fell, causing it to dry out, Ghonmein said.

Nowadays, the lost branch is hidden beneath farmland and desert, the researchers wrote.

Hader Sheisha, an associate professor of natural history at the University of Bergen in Norway who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science in an email that "these findings show clearly that the Nile hydrological [network] was indispensable for building the pyramids."

The findings did not surprise Sheisha. She was the lead author of a 2022 study that found that a branch of the Nile went close to the Great Pyramid at Giza, making it easier to transport goods and materials. Sheisha also noted that earlier studies proposed that goods were brought to pyramid sites through river branches that have since dried up.

"The new study could be considered as a contribution to these previous hypotheses," Sheisha said.

Zahi Hawass, a former Egyptian antiquities minister, also told Live Science that the finds are not surprising. An ancient papyrus that contains the logbook of a man named Merer notes that while the Great Pyramid was being constructed, workers brought materials to it by way of a nearby harbor. Additionally, excavations conducted at Giza have revealed evidence of a harbor.

Nick Marriner, a research director at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) who wasn't involved in the study, spoke positively of the research, as it "demonstrates that, when the pyramids were built, the geography and the riverscapes of the Nile floodplain differed significantly to those of today," Marriner told Live Science in an email. "Reconstructing how, when and where these former Nile channels evolved can help us to understand how the ancient Egyptians harnessed the natural environment, and the Nile's flood cycles, to transport building materials to the site for the construction of the pyramids."

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus