2,500-year-old skeletons with legs chopped off may be elites who received 'cruel' punishment in ancient China

The amputated legs of skeletons belonging to two men who lived in ancient China suggests that they were punished for alleged crimes 2,500 years ago.

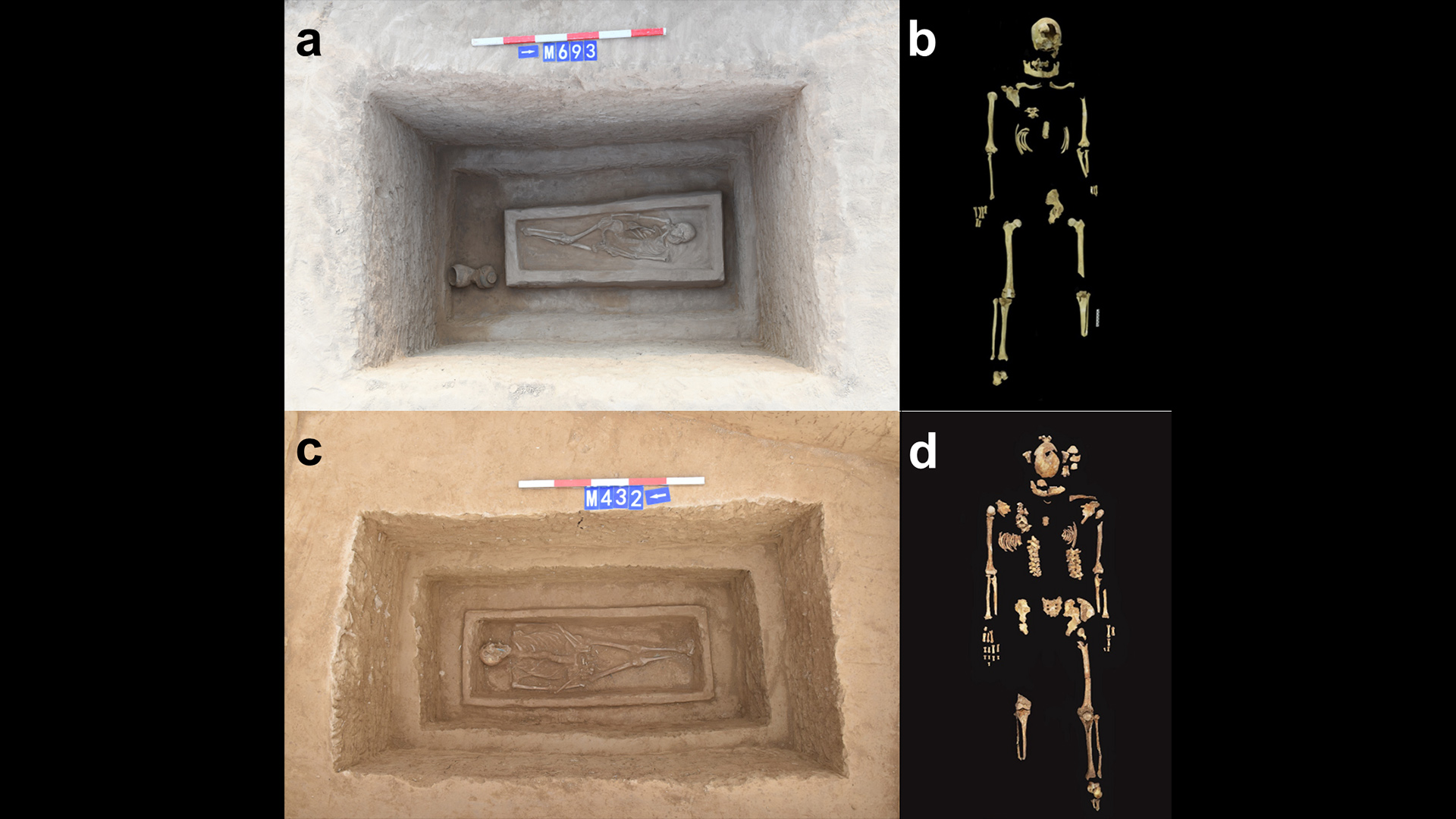

Two ancient skeletons, each missing a part of the lower leg, recovered from graves in China were of elite individuals whose legs were amputated as punishment around 2,500 years ago, during the Eastern Zhou dynasty, a new study suggests.

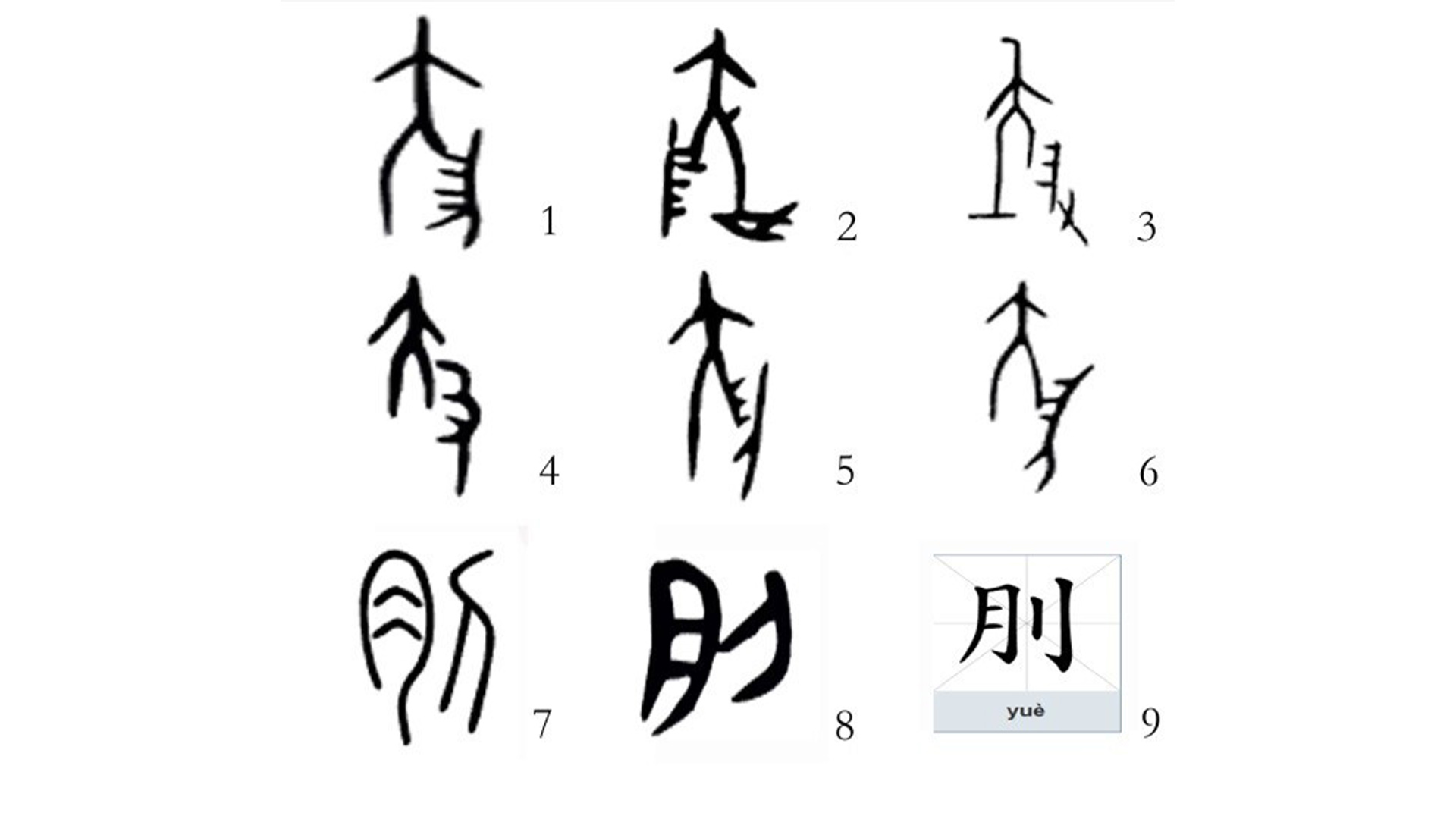

The discovery provides a rare glimpse into the brutal punishment method, called "yue," from ancient China, the researchers said.

"Such discoveries, along with some previous findings, reflect the cruelty of the penal system in early China," study senior author Qian Wang, a professor of biomedical sciences at the Texas A&M University School of Dentistry, told Live Science in an email.

However, not everyone agrees that these men were punished with yue, saying that they could have received amputations for other reasons.

Related: Ancient Chinese burials with swords and chariot cast light on violent 'Warring States' period

The skeletons — along with objects such as copper belt hooks, stone tablets and pottery — were excavated from an ancient graveyard in Henan province. Both skeletons were found inside two-layered coffins in graves with north-south orientation, possibly indicating high social status.

Both individuals were missing the bottom fifth of one of their legs; one skeleton was missing part of the left leg, and the other was missing part of the right. The lower ends of the remaining lower-leg bones (tibia and fibula) showed signs of healing and bore no cut marks. These findings hint at deliberate and skilled slicing and proper wound care, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers analyzed the skeletons with several methods, including computed tomography (CT) scans and radiocarbon dating. They found that the bones belonged to men who lived around 550 B.C., during the Warring States Period, when the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 to 256 B.C.) held sway over the region.

At the time of his death, the man missing part of his left leg was 40 to 44 years old, while the one without part of his right leg was 45 to 55 years old. The men's wounded tibias and fibulas had healed by fusing together and forming a bony bump, and lacked cut marks indicative of repeated blows from a clumsy job.

An analysis of the bones' isotopes, or variations of elements that have a different number of neutrons in their nuclei, revealed that both men had diets rich in proteins and a type of carbon seen in plants like millet, which matched diets known for the Eastern Zhou aristocratic class.

Based on the coffin layers, the orientation of the graves and the men's diets, the researchers deduced that the two men were of high social status.

This determination is supported by the writings of the philosopher Zhuangzi. Coffin layers of three and above were reserved for higher officers, nobility and royalty, who were also exempt from the Zhou penal system. This meant that the two men were possibly low-ranking officers of the Zhou dynasty, according to the study, which was published March 16 in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

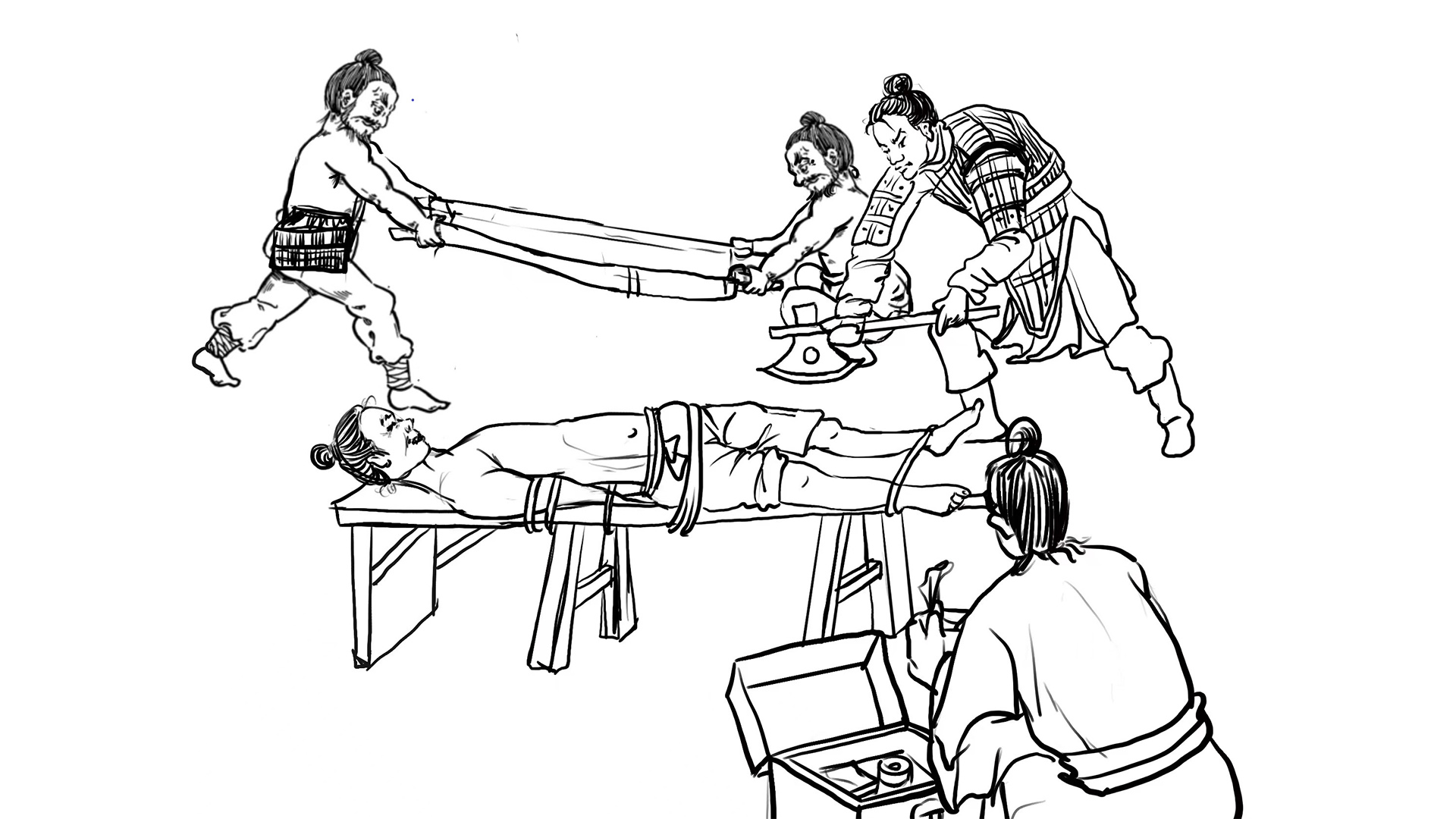

Based on the men's social status and the Zhou penal code, the researchers suggested that the most plausible explanation for the missing legs was the yue punishment method. The team ruled out other causes, like congenital absence of limbs, diseases necessitating amputation (such as diabetes, bone cancer or leprosy) and sacrificial amputation.

Yue, or punitive amputation, was practiced in ancient China beginning in the Xia dynasty (2100 to 1600 B.C.) and was abolished by the Han dynasty in the second century B.C. The Zhou penal code prescribed punitive amputations for myriad felonies, "including deceiving the monarch, fleeing from duties, stealing, and so on," Wang said. On some occasions, it could also be a "reduced" punishment, in lieu of the death penalty, to "reflect leniency," he said. The right leg was amputated for crimes deemed more serious than the ones warranting left-leg amputation.

A clean amputation followed by a good recovery reflects a well-established amputation protocol that may have involved doctors and nurses to facilitate the amputation and post-execution care, the researchers said.

"What's interesting is that there's clearly healing and recovery, and good archaeological context to suggest that they were not poor people," Kate Pechenkina, professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at Queens College, City University of New York and the CUNY Graduate Center who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

But she suggested an alternative reason for the missing portions of the skeletons' legs. "Amputation due to trauma is a simpler explanation," she said.

It's likely that the amputation was performed to manage an infected fracture or an injury, like from a horse smashing the foot, Pechenkina said. "You amputate the foot," she said." You can't fix a smashed foot."

The authors noted this in the study, too, writing that "surgical procedures to treat trauma" could be an explanation for the amputations.

Soumya Sagar holds a degree in medicine and used to do research in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science, Discover, and Mental Floss. He is a passionate science writer and a voracious consumer of knowledge, especially trivia. He enjoys writing about medicine, animals, archaeology, climate change, and history. Animals have a special place in his heart. He also loves quizzing, visiting historical sites, reading Victorian literature and watching noir movies.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus