Trail of crabs leads scientists to remarkable underwater discovery

Scientists have discovered a never-before-seen hydrothermal vent teeming with life off the Galápagos Islands by following a long trail of squat lobsters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have discovered a new hydrothermal vent field in the Galápagos — with the help of crabs.

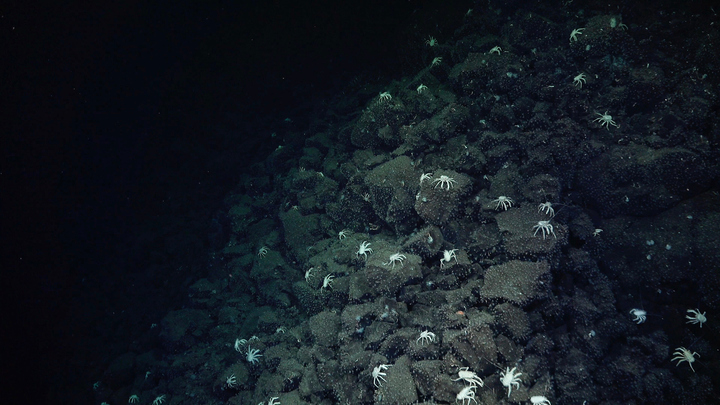

While the team used an array of sensitive equipment to zero in on the possible location, the sight of increasingly dense populations of galatheid crabs (genus Munidoposis), also called squat lobsters, ultimately led them to the new field. It is located in the Galápagos Spreading Center (GSC), a divergent boundary between the

Cocos and Nazca tectonic plates roughly 250 miles (400 kilometers) north of the Galápagos Islands. It is located in the Galápagos Spreading Center (GSC), a divergent boundary between the

Cocos and Nazca tectonic plates roughly 250 miles (400 kilometers) north of the Galápagos Islands.

By following these ghostly white crustaceans, which aggregate around deep--sea vents, they found a field extending over 98,800 square feet (98,800 square feet (9,178 square meters). Crew members dubbed it the "Sendero del Cangrejo," or "Trail of the Crabs."

The research, organized by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, was conducted in the same region where the very first hydrothermal vent field was confirmed in 1977 in the Eastern GSC. The current study was conducted in the Western GSC).

There are roughly 550 known hydrothermal vents in the world, only half of which have been visually confirmed. The rest have been inferred from chemical and temperature signatures in the water column.

Hydrothermal vents occur when water seeps into the rock of the seafloor at either a plate margin, like the one at the GSC, or at a hotspot, where magma is rising to the surface in another area of the plate. In both cases, the water is heated by magma and leaches minerals from the surrounding rock. The heat causes the water to rise, and it is then expelled through fissures in the rock, often forming what are known as chimneys.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To locate the vent, the team first began searching the general region where a chemical anomaly had been identified in 2008. "One of the anomalies that we look for is a lens of low oxygen water," expedition co-leader Jill McDermott, a chemical oceanographer at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, told Live Science. "Oxygen is completely removed through circulation in the seafloor. So the water that's expressed at the seafloor is devoid of oxygen."

The researchers followed this plume of oxygen-poor, chemically enriched water until it disappeared — suggesting they were close to the vent.

They then launched a remotely operated vehicle to inspect the seafloor and followed the trail of squat lobsters to the vent field itself. There, they found a thriving ecosystem of uniquely adapted organisms now known to be typical of hydrothermal vent environments. "There were giant tube worms, which can be a couple meters long. There were very large clams, sometimes called dinner plate clams, as well as mussels," said Roxanne Beinart, a biological oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island who co-led the expedition.

The team was particularly intrigued by the presence of the tube worms as they are absent from other sites they inspected on the expedition. "It's possible that what we're seeing here is a series of different successional stages, where one vent field is farther along its succession, and the tube worms are now gone," Beinart said.

The group intends to spend the next several years analyzing that data and comparing notes in the hopes of advancing our understanding of these remote environments.

Richard Pallardy is a freelance science writer based in Chicago. He has written for such publications as National Geographic, Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Discover Magazine.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus