Super-healing shark regrows its fin after humans cut a huge chunk off

The shark is only the second in history to be observed regrowing a dorsal fin.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A super-healing shark regrew a section of its fin after suffering a traumatic injury at the hands of humans near Jupiter in Florida, researchers have found.

The silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) had a satellite tag fitted to its dorsal fin in June 2022 so researchers could track its migration. A few weeks later, an unknown person cut out the tag and left the shark with a devastating wound. Local diver John Moore saw the shark's tag was missing and contacted the researchers.

"I told him it would be impossible to miss the satellite tag on the dorsal fin, so he would know if it was one of our sharks," study author Chelsea Black, a doctoral student at the University of Miami, told Live Science in an email. "That’s when he sent me the first photo showing the huge hole of where a tag had been."

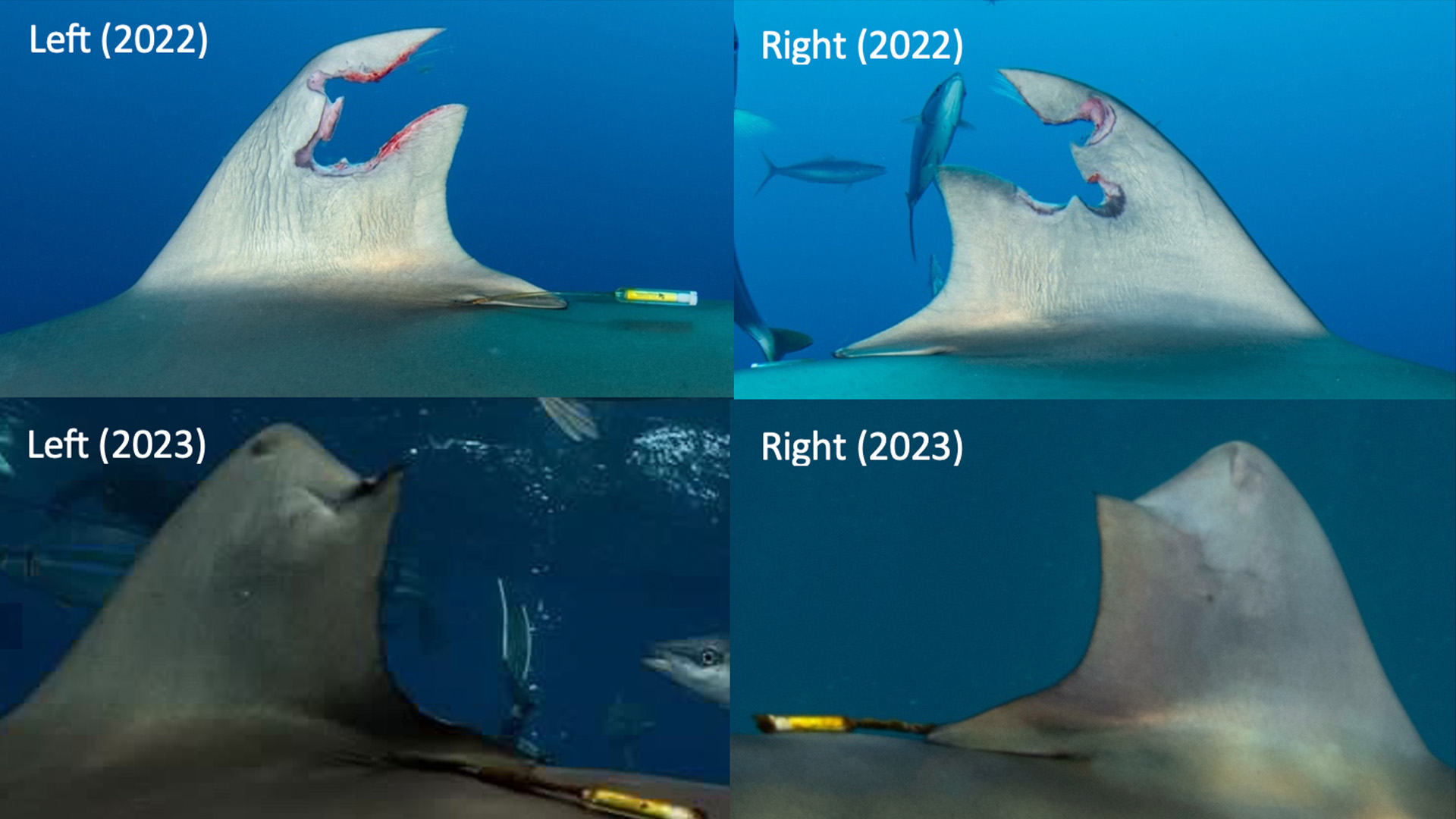

Black didn't expect to see the shark again, as the injury was extensive and she could no longer track the animal. But, remarkably, almost a year later, the shark returned to the same waters and was photographed with a rejuvenated — albeit slightly stumpy — fin.

"It was shocking!" Black said. "My first reaction was relief that the shark was still alive, as that was a traumatic wound that could affect his swimming ability or create a significant infection."

This is the first time researchers have observed a silky shark regrowing its dorsal fin and only the second recorded case of dorsal fin regeneration in any shark, according to the study, published Dec. 14 in the Journal of Marine Sciences.

Related: Pregnant megamouth shark seen for 1st time after female washes up dead with 7 pups

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Silky sharks grow to around 10 feet (3 meters) long and live in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History. They are vulnerable to extinction due to overfishing, but it's illegal to capture or kill them in Florida.

The silky shark's injuries in 2022 were precise cuts that traced the outline of the satellite tag, so the most plausible explanation is that humans deliberately removed the tag with a sharp object, according to the study. Black doesn't know who removed the tag but doubts their intention was to help the shark.

"It’s more likely that the shark was caught by a fisherman and they either cut out the tag to try and sell it, or they just didn’t want scientists to study them," Black said. "Sharks can be seen as a nuisance to some people, so you can imagine there is a group of people who wouldn’t want us to increase conservation measures."

Black documented the rare fin regeneration by analyzing diver photographs taken 322 days apart. The photographs revealed that the shark lost 20.8% of its fin in the initial injury, and it healed back to 87% of its original size, according to the study.

Researchers are still learning how sharks regenerate their fins because it's so rarely observed. Black thinks the new fin is mostly scar tissue but can't be sure as nobody has ever dissected a regenerated shark fin.

Sharks naturally experience a lot of injuries — often due to aggression and predation attempts from other sharks — so they've evolved to heal quickly. Their healing tricks include immediate anti-inflammatory responses to injuries, according to the study.

"There's a reason that sharks have been evolving for hundreds of millions of years, surviving multiple mass extinction events," Black said. "This story just proves how resilient they can be."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus