Ancient 'curse tablet' may show earliest Hebrew name of God

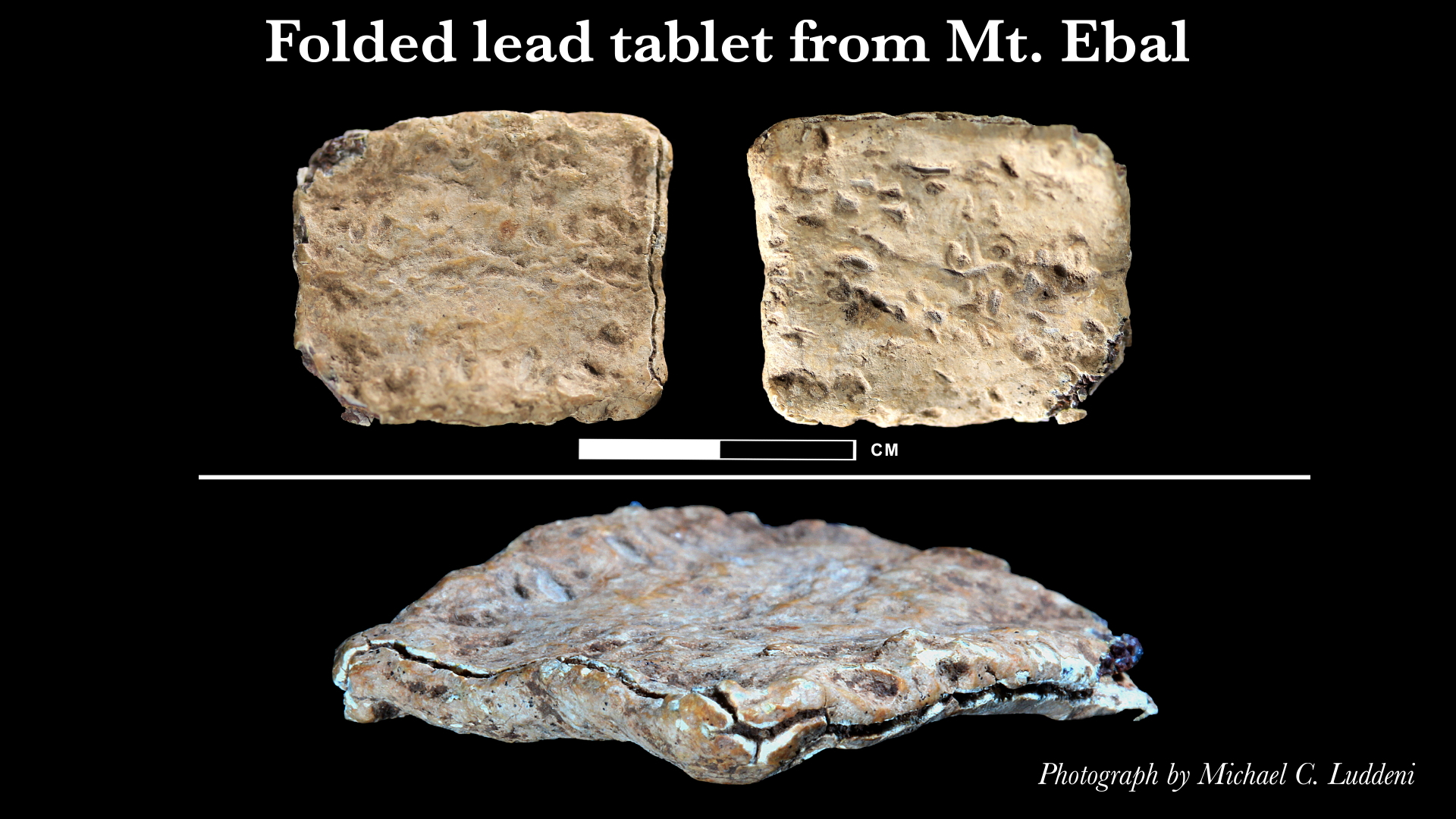

The tablet is barely larger than a postage stamp.

Updated Dec. 6, 2023: The original findings were published in a paper in May 2023 in the journal Heritage Science. In December 2023, archaeologists skeptical of the find published three articles arguing that the so-called curse tablet may actually be a fishing weight, and what looked like Hebrew letters on it were made by natural weathering.

Archaeologists working in the West Bank say they’ve discovered a tiny "curse tablet," barely larger than a postage stamp, inscribed with ancient letters in an early form of Hebrew that call on God to curse an individual who breaks their word.

While the dating hasn't been verified and the find hasn't been published in a peer-reviewed journal yet, its discoverers think the tablet is at least 3,200 years old.That would make the inscription the earliest-known Hebrew text by several hundred years, and the first to contain the Hebrew name of God, they say.

However, several archaeologists who were not involved with the discovery say they can't assess the find until details of it are published in a scientific journal; and at least one expert cautions the tablet may not be as old as its discoverers claim.

Project leader Scott Stripling, an archaeologist and the director of excavations for the U.S.-based Associates for Biblical Research (ABR), told Live Science that his team found the curse tablet high on Mount Ebal, just north of the city of Nablus, in December 2019.

Stripling and his colleagues announced the find at a press conference in Houston, Texas, on March 24.

Related: Evidence of Hanukkah's Maccabee rebellion unearthed in Israel

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Details of the tablet — a piece of folded lead sheet about an inch high and an inch wide (2.5 by 2.5 centimeters) — will be published in an archaeological journal later this year, but the team wanted to make the announcement before news of the object leaked out, Stripling said.

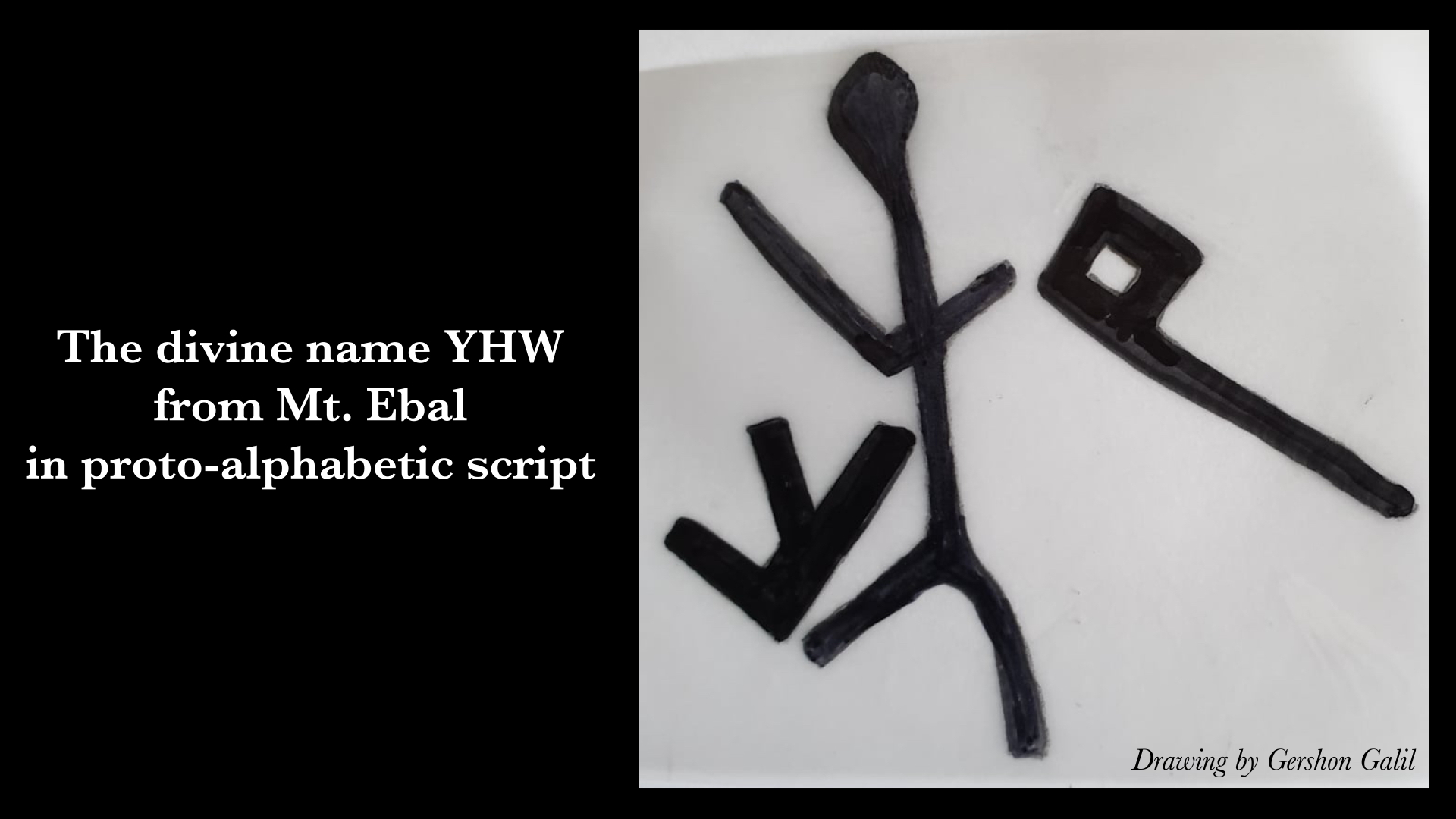

Forty proto-alphabetic letters, inscribed in an early form of Hebrew or Canaanite on the outer and inner surfaces of the folded lead tablet, warn what would happen if someone under a covenant — a legally binding agreement — didn't meet their obligations.

"Cursed, cursed, cursed — cursed by the God Yahweh," the inscription reads, using a three-letter form of the Hebrew name of God that corresponds to the English letters YHW.

Curse tablet

Stripling and his team found the curse tablet by a process of "wet-sifting" material — that is, washing sediments with water — that had been discarded during archaeological excavations on Mount Ebal in the 1980s.

This particular sediment pile was likely the cast-off material from excavations of the ancient stone structure called "Joshua's Altar," high on a ridge of the mountain, he said.

Some think the structure may be where the biblical figure Joshua – the successor to Moses as leader of the Israelites – sacrificed animals to God, while others think it is a sacrificial altar from the Iron Age, several hundred years later.

The stratigraphy of the site — in other words, the dates of different layers of earth determined by archaeological excavations — suggest that the tablet dates to around 1200 B.C. at the very latest, and perhaps as early as 1400 B.C., Stripling said.

An analysis of the chemical isotopes of the lead used in the tablet shows that it came from a mine in Greece that was active during this period, and the very early proto-alphabetic letters — some of which still have forms derived from earlier pictorial symbols, or hieroglyphs — match the presumed dates.

Related: Ancient 'hangover prevention' ring found in Israel

According to the Book of Deuteronomy in the Hebrew Bible, Mount Ebal was one of the first locations in Canaan seen from afar by the ancient Israelites after they had been led out of an eastern wilderness by Moses.

In a biblical passage, Moses called on one group of Israelite tribes to proclaim curses from Mount Ebal, while another group of ancient Israelite tribes proclaimed blessings from nearby Mount Gerizim.

The newly-found object is the only known example of a "curse tablet" found at the site, although they are common at Jewish sites elsewhere that date from the much later Hellenistic and Roman periods, after about the late fourth century B.C., Stripling said.

Ancient Israelites

If the date can be verified, the inscription on the curse tablet would push back the earliest-known date for literacy among the ancient Israelites by several hundred years; until now, the earliest evidence was the Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription, dating from about the 10 century B.C., according to researchers at Israel's University of Haifa.

ABR describes itself on its website as a nonprofit ministry dedicated to demonstrating the historical reliability of the Bible, and Stripling believes the Mount Ebal curse tablet could be evidence for the biblical story of the ancient Israelites arriving in the region — then called Canaan — from farther east.

"We have an ancient text saying that the Israelites arrived around 1400 [B.C.], and then we have evidence of them on a mountain where the Bible says that they were, writing a language that the Bible says that they used," Stripling said. "I think a fair-minded person might be willing to draw the conclusion, inductively, that there were Israelites there."

Other archaeologists, however, suggest there's little evidence of the biblical story that the Israelites were led to Canaan by Moses; instead, archaeology suggests that at least some of the Israelites originated in the Canaanite lands that became the Israelite kingdoms.

Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist and professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, who wasn't involved in the discovery, cautioned that there is a "big gap" between the description of the find on Mount Ebal and the claims of the researchers regarding the implications for biblical studies and archaeology.

No detailed analysis of the claims would be possible until a scholarly article is published on the discovery, Finkelstein said; but he noted the curse tablet wasn't found in a clear archaeological context during an excavation, but in a pile of debris dating from an excavation in the 1980s.

He also questioned the proposed dating, noting that comparison of the Mount Ebal site to other sites dated by radiocarbon analysis suggest it may date from the 11th century B.C. — perhaps two centuries or more later than what was claimed — and he suggested the decipherment of the inscription on the tablet could also be subject to interpretation.

"In general, I am irritated by sensational claims of discoveries which ostensibly change everything that we know about the Bible and the history of ancient Israel," Finkelstein said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.