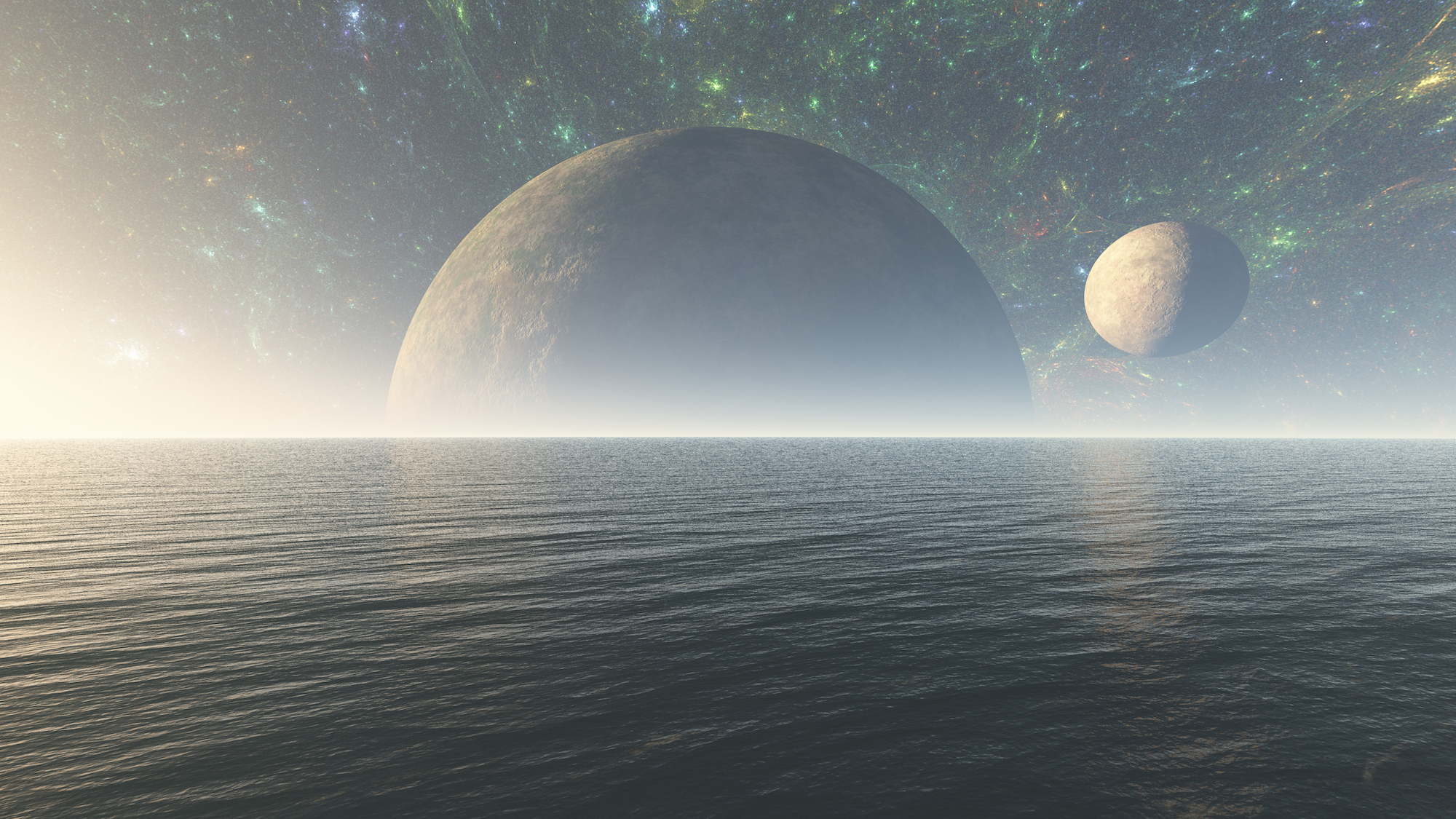

Alien Oceans Could Hold Way More Life Than Earth’s Waters Ever Did, New Research Suggests

Alien worlds that favor strong ocean currents could be overflowing with life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth is the only planet in the universe known to harbor life, but new research suggests that some distant worlds could put the Blue Marble's biodiversity to shame.

It's not because these other, hypothetically habitable exoplanets are devoid of humans (though Earth's biodiversity would definitely be looking better without us). Rather, a planet's potential to harbor life could hinge on how well its oceans move nutrients around the world, University of Chicago geoscientist Stephanie Olson said today (Aug. 23) in a presentation at the Goldschmidt Geochemistry Congress in Barcelona.

"NASA's search for life in the universe is focused on so-called Habitable Zone planets, which are worlds that have the potential for liquid water oceans," Olson said in a statement about her research. "But not all oceans are equally hospitable — and some oceans will be better places to live than others due to their global circulation patterns."

One circulation pattern in particular — known as "upwelling" — may be key to fostering life in the seas, Olson said. Upwelling occurs when wind rushes along the ocean's surface, creating currents that push deep, nutrient-rich water up toward the top of the sea, where photosynthetic plankton live. The plankton feed on these nutrients, allowing them to produce organic compounds that feed larger organisms, which in turn become meals for still-larger organisms, and so on up the food chain.

As members of the food chain die and decompose, their organic remains sink to the bottom of the sea, where they may get caught in another upwelling and feed the surface life again. Thanks to this efficient, underwater recycling system, biodiversity tends to thrive in upwelling areas on Earth (mainly near the coasts). The same is likely true on habitable exoplanets, Olson said, which means that planets with conditions that favor more ocean upwelling may also favor strong biodiversity.

To find out what sorts of conditions lead to productive upwelling, Olson and her colleagues used a NASA simulator called ROCKE-3D to test how atmospheric and geophysical factors contribute to ocean currents.

"We found that higher atmospheric density, slower rotation rates and the presence of continents all yield higher upwelling rates," Olson said. "A further implication is that Earth might not be optimally habitable — and life elsewhere may enjoy a planet that is even more hospitable than our own."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While these findings don't have any direct applications to the 4,000 or so exoplanets that have been discovered so far, they could inform the way scientists look for habitable worlds in the future. Ideally, Olson said, future generations of telescopes will be built that better analyze features like atmospheric density and rotation rate, which could offer a quick glimpse into a world's habitability. With tech like that, we should be able to find the space-octopus homeworld in no time.

Olson's new study has yet to appear in a peer-reviewed journal.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 15 Amazing Images of Stars

- 9 Strange Excuses for Why We Haven't Met Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus