The First Runner's High: Jogging Separated Humans from Apes

No offense, but your long neck, flat face and well-endowed buttocks are the reason you have an edge over pigs and monkeys in the marathon.

And you can thank your hungry ancestors for these useful anatomical features, which may also have led to the big brain you now enjoy.

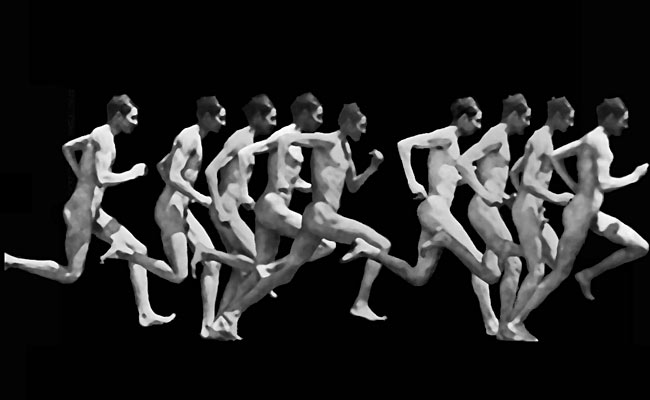

A new study suggests the need for endurance made us what we are. Hunting or scavenging on the African savannah was the genesis of the Nike empire, the thinking goes. Those who ran well separated themselves from the pack of apes and became the earliest humans, eating protein that enlarged their brains.

Running got us out of the trees and made us smarter.

"We are very confident that strong selection for running -- which came at the expense of the historical ability to live in trees -- was instrumental in the origin of the modern human body form," said University of Utah biologist Dennis Bramble.

The idea is presented in the Nov. 18 issue of the journal Nature.

Run, don't walk

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The conventional thinking has been that running was a mere byproduct of upright walking, known as bipedalism.

But the ape-like species Australopithecus is thought to have gone bipedal 4.5 million years ago while continuing to climb trees, too. It took another 3 million years or more for Homo sapiens to evolve from Australopithecus.

"So is walking going to be what suddenly transforms the hominid body?" Bramble asks. "No, walking won't do that, but running will."

Bramble and Harvard University anthropologist Daniel Lieberman examined 26 human traits that contribute to our ability to give chase. They compared many of these to fossils of our ancestors. Compared to us, Australopithecus had long forearms, short legs, and terrible arches. It walked around with a permanent shoulder shrug ill suited for jogging.

Pigheadedness

Apes aren't the only poor runners.

At first, Bramble and Lieberman wondered why pigs don't pursue the runner's high. They found swine lack something we and some other animals have, a "nuchal ridge" at the skull base. The ridge attaches to tissue that keeps the head steady while we run. Chimps and the earliest prehumans lack the ridge, too.

No neck and a wimpy hind end make apes lousy marathoners.

Moreover, chimps have burly shoulders connected to their skulls, "the better to climb trees and swing from branches," Lieberman points out. "The shoulders of modern humans are disconnected from our skulls, allowing us to run more efficiently."

So why would evolution have selected for the development of these features?

Biologist David Carrier, also of the University of Utah, provided a possible answer in previous research. Before humans had invented the bow and arrow, Carrier reasons, it would have been advantageous to wear down prey with an endless pursuit.

Carrier, who was not involved in the latest study, showed that differences in how humans breathe and sweat suited them for endurance. Further, he found evidence that Navajo Indians and other primitive cultures were able to run down very swift animals.

The new study provides more detailed anatomical evidence to support Carrier's earlier hypothesis, he told LiveScience.

"I think it's very well thought out," Carrier said of the Bramble and Lieberman study. "I think there's strong support for their arguments."

Importantly, the food that early humans could catch by simply outlasting their prey -- meat -- would have changed everything.

"What these features and fossil facts appear to be telling us is that running evolved in order for our direct ancestors to compete with other carnivores for access to the protein needed to grow the big brains that we enjoy today," Lieberman said.

Big butt, flat face, lots of sweat

Other things that make you born to run, according to the study:

- Compared to apes, your flat face, small teeth and short snout shift the center of mass of your head back, so it doesn't bob up and down when you jog.

- Your height and, ahem, narrow physique create more skin surface for sweating and cooling.

- Human heels, toes and arches are well designed for pushing off and absorbing shock.

- A ligament ties the back of your skull to your vertebrae, acting like a shock absorber. Large vertebrae and disks assist in allowing a less-jarring gait.

- Your upper and lower body move independently, making it easier to balance while your legs swing. Short forearms help, too.

- When your head sweats, blood in veins near the surface is cooled. The veins pass near carotid arteries, helping cool blood on its way to the brain.

The human backside helps, too. A good-sized hiney stabilizes your trunk. Bramble asks: "Have you ever looked at an ape? They have no buns."

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.