The Invisible AIDS Victims: How Women Cope

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

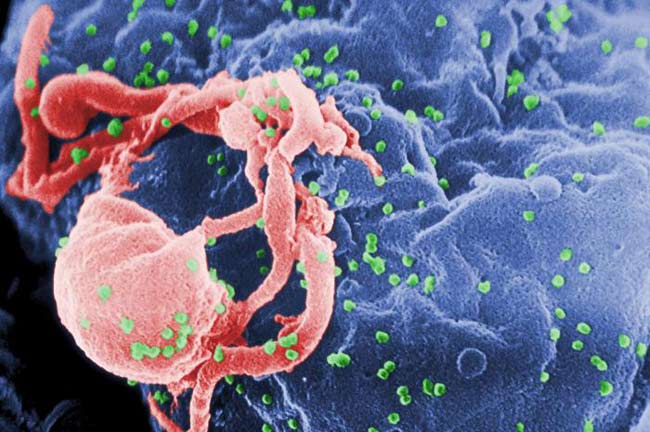

When people picture faces of famous Americans who are personally affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, they tend to see Magic Johnson, Ryan White, Rock Hudson, Greg Louganis, or Freddy Mercury, to name a few. Seldom, if ever, is the deadly virus associated with the face of a woman.

Now in a new study that's the first of its kind, Celeste Watkins-Hayes is examining how women cope economically with the disease, and her findings could influence today's health care debate.

"For a long time, women with HIV were somewhat invisible in the research field and in our common knowledge," said Watkins-Hayes, associate professor of African American studies and sociology at Northwestern University. "AIDS and HIV got tagged as a 'man's disease' early on in the epidemic even though there were women being infected as well."

In her study, Watkins-Hayes is exploring the economic experiences and related social processes of women living with HIV/AIDS in Chicago. By following a group of women over the course of two years, she plans to uncover which economic situations allow infected women to manage their health most effectively and continue to contribute to society.

Watkins-Hayes' previous research showed that women living with the virus were able to find resilience despite their situations, but having economic stability was a key ingredient to doing so. Most of the women in the study received health care, medication, and social services through the Ryan White Care Act, which is the largest provider of assistance for people with HIV/AIDS in the United States. With funds intact, women were better able to care for their children and prevent HIV from developing into full-blown AIDS.

"In the absence of those resources, the lives of these women would have been devastated," said Watkins-Hayes. "When they didn't have to worry about where their medication and other basic needs were coming from, they could focus on their families and personal wellness. But that is not the case for everybody living with HIV in the U.S."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study will look beyond access to medications to explore other economic resources that help women effectively manage their health. When women do not have stable incomes large enough to cover expenses, their focus can move from protecting their health to gathering resources to survive. They may be more likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods where crime and drugs are prominent and more likely to rely on intimate partners for their basic financial needs. This puts them in situations where they may be exposed to non-monogamous partners or sex work to meet their financial needs, which can further spread the virus.

"Much of the work we're doing across the country and globally shows there is a relationship between poverty and HIV in terms of economic disadvantage creating a social context of risk," Watkins-Hayes said.

Watkins-Hayes will follow women from all demographic backgrounds and compare their economic profiles. Among the groups she will study are women who take care of themselves with government funds or disability benefits from social security, women who participate in the labor market, women who receive help from non-profit organizations, and women who rely on a variety of sources to make ends meet.

"When we know what works, then we can figure out how to intervene with policy and programs to keep this epidemic from exploding completely," she said.

As the research is conducted, Watkins-Hayes will disseminate the findings through meetings, conferences, and a series of papers. She also plans to create a web site and policy briefs where people can follow the progress of her work.

"A whole arm of this study is dedicated to communicating to the public about what we're doing and how we're doing it," she said. "I don't want the community to feel like this research happened in an ivory tower and ended up in a journal that is only read by academics."

Funded by an Early Career Development (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation, Watkins-Hayes will begin interviewing research subjects this winter.

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- Video: AIDS Was Here Earlier

- Health Care Debate Based on Lack of Logic

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus