Invisible Matter Loses Cosmic Battle

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

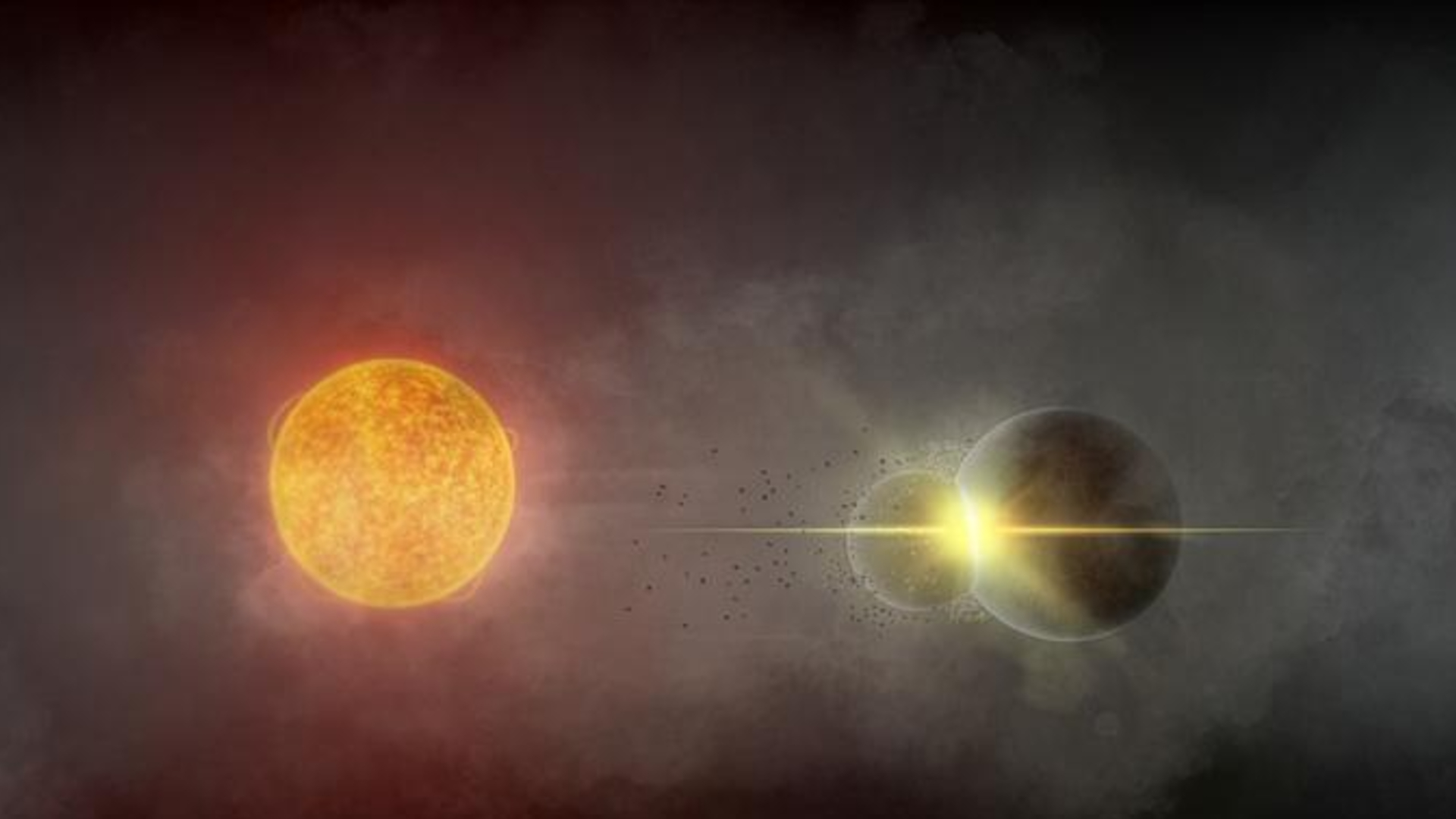

In a cosmic battle of sorts taking place in the centers of galaxies, stellar forces muscle up and kick out brewing invisible matter. The result, finds a new study, evens out the amount of invisible matter held in galactic cores, resolving a cosmological puzzle.

The invisible stuff, called dark matter, is thought to make up as much as 90 percent of the universe's mass. Astronomers have never directly observed this mysterious matter, as it doesn't emit or reflect visible light or other electromagnetic radiation. Instead, they infer its existence based on its gravitational effects on visible matter like stars and galaxies. (For instance, dark matter makes galaxies spin faster than otherwise expected.)

Astronomers have long tried to explain theoretical models that predict there should be much more dark matter in the central regions of dwarf galaxies than observations suggest is the case.

Article continues below?One of the most troublesome issues concerns the mysterious dark matter that dominates the mass of most galaxies," said Sergey Mashchenko of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at McMaster University in Ontario.

Maschenko and his colleagues used supercomputer simulations to illustrate galaxy formation early in our cosmic history?about a billion years after the Big Bang, the theoretical start of the universe as we know it. The simulations showed the violent processes galaxies suffer at their births, when dense clouds of gas collapse to form massive stars, which then end their lives quickly as explosive supernovas.?

It is well established that these massive stars can inject large amounts of energy into their galactic neighborhoods through the explosions and also constant emissions of charged particles called stellar winds. The energy can push interstellar gas to nearly sonic speed, which for gas at a typical temperature is about 6 miles per second (10 kilometers per second).

Still, debate has persisted over whether this stellar feedback could turn the spike in dark-matter density (predicted by theory) into the observed flat core in the central regions of dwarf galaxies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The simulations showed that the stellar wind and explosions shock the interstellar gas, pushing it back and forth like water sloshing in a cosmic bathtub. That sloshing kicks most of the dark matter out of the center of a dwarf galaxy in the simulation, bringing into agreement theoretical predictions and observations.

The researchers say their results, detailed online last week by the journal Science, will force cosmologists to rethink the role of interstellar gas in the formation of galaxies and could lead to a better understanding of dark matter.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus