Even the Simplest Creatures Favor Family

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When the going gets tough, most animals instinctively cling to family. Now, scientists find that even single-celled amoebas, the simplest creatures known, favor their own in times of need.

Typically found in freshwater, amoebas will also sacrifice themselves for the good of the family, researchers report in the Aug.24 issue of the journal Nature.

"By recognizing kin, a social microbe can direct altruistic behavior towards its relatives," said Natasha Mehdiabadi, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Rice University.

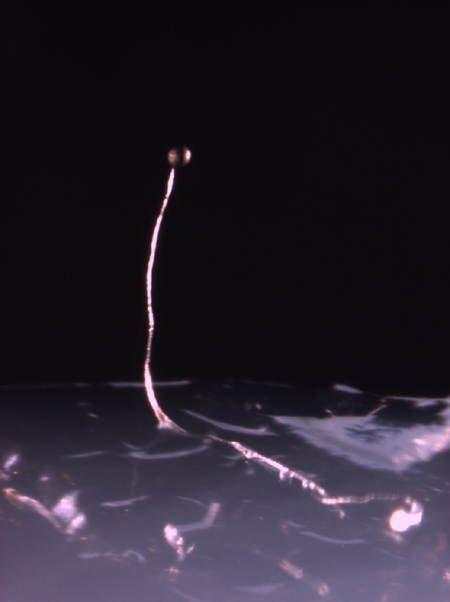

Mehdiabadi and colleagues studied a group of amoebas called Dictyostelium purpureum, common soil microbes that feed on bacteria. In nature, when there's a shortage of food, these amoebas get together by the thousands and form into long narrow slugs and then into hair-like fruiting figures that look like mushrooms.

These miniature mushrooms have a freestanding stalk and spores that sit on them. A creature passing by eventually carries the spores away, so that the amoebas can start the life cycle again.

In order to scatter the spores, some amoebas, however, must form the stalk and sacrifice themselves in the process. When Mehdiabadi starved a group of these amoebas in the lab, they formed dozens of slugs and fruiting bodies. In each experiment she cultured a pair of strains. At the end, each fruiting body contained either the one strain or the other, each strain staying with its own.

These experiments showed that these organisms preferentially associate with their own kin, said Joan Strassmann, a biologist at Rice University.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus