Gasping for Air: Lack of Oxygen Worsened the 'Great Dying'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The biggest of Earth's mass extinctions may have left animals gasping for air, a new study finds.

The Great Dying, as it is called, occurred some 250 million years ago. Roughly 90 percent of all marine life died, as well as nearly three-quarters of all land plants and animals. It marks the transition from the Permian geological period to the Triassic.

While fossils reveal the extinction in concrete terms, its causes are less well known. Scientists have blamed the massive die-off on an asteroid, volcanoes, global warming, and any combination thereof.

Now Raymond Huey and Peter Ward of the University of Washington have shown that a reduced supply of oxygen could explain high extinction rates that preceded the Great Dying, as well as the very slow recovery that followed.

Currently, oxygen makes up about 21 percent of our atmosphere, but in the early Permian period it was 30 percent. From this invigorating level, it fell to about 16 percent at the time of the Great Dying and over the next 10 million years continued to drop to 12 percent.

"Oxygen dropped from its highest level to its lowest level ever in only 20 million years," Huey said today.

With oxygen only 16 percent of the atmosphere, animals at sea level breathed air similar to that at the top of a 9,200-foot mountain today. At 12 percent, the corresponding elevation would be 17,400 feet. If you've ever climbed such a mountain, you know the effect.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Animals that once were able to cross mountain passes quite easily suddenly had their movements severely restricted," Huey said.

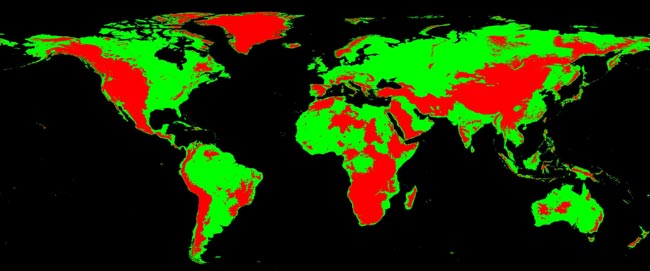

This contradicts the prevailing view of Pangea, the super-continent that existed back then and which later broke apart to form all the modern continents. Most paleontologists considered it a "superhighway" on which species could range freely, Ward said. But with so little oxygen, high elevations would act as barriers.

Secluded populations would be more vulnerable to other environmental challenges, like severe climate change. It would also take longer for isolated organisms to bounce back.

The findings were published in the April 8 edition of the journal Science.

- Global Warming Likely Cause of Worst Mass Extinction Ever

- Volcanoes Snuffed Out Most Life 250 Million Years Ago

- The 5 Worst Mass Extinctions

Pangea

Pangea began to break up about 225-200 million years ago. This animation shows how it unfolded.

SOURCE: USGS

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus