Medieval Letter Reveals Bawdy Nun Who Faked Her Death to Escape Convent

Medieval nun fakes death to escape convent and enjoy a life of carnal lust. Sounds like the basis for a juicy novel, but this really happened during the 14th century in England.

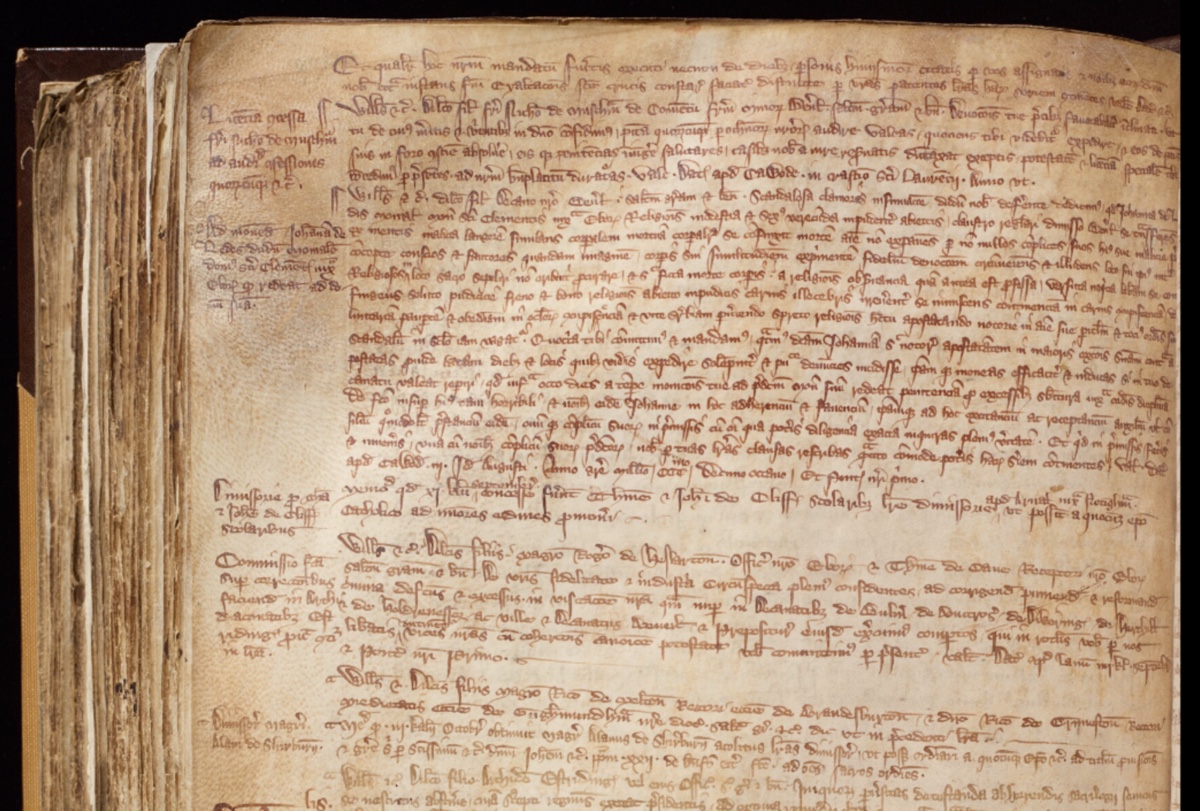

Archivist and historian Sarah Rees Jones discovered the real-life tale while investigating the Registers of the Archbishops of York, which recorded the business of archbishops from 1304 to 1405, as part of a project to make the contents of the documents accessible online.

In a letter (in the registers) dating to 1318, Archbishop William Melton describes a "scandalous rumor" he heard, detailing the blasphemous behavior of a nun named Joan to the Dean of Beverley, who was responsible for an area of Yorkshire some 40 miles (64 kilometers) east of York, said Rees Jones, a medieval historian at the University of York and principal investigator on the project. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

The letter requests the dean's help in finding Joan and demanding that she return to her convent in York, Rees Jones told Live Science. "It is copied into the archbishops' registers, which are the main focus of our project," she added.

To try to get away with her escape, Joan apparently created some kind of body double that the other nuns would bury as her own. "My speculation is that she used something like a shroud and filled it with earth, hence its dummy-like appearance," Rees Jones said. "People were commonly buried in shrouds."

As for what Joan was escaping to, described in the letter as her "carnal lust," Rees Jones can only speculate.

"This may mean no more (in modern terms) than enjoying the material pleasures of living in the secular world (abandoning her vow of poverty), or it may mean entering into a sexual relationship (abandoning her vow of chastity)," Rees Jones wrote in an email to Live Science. "We do know that other religious [people] abandoned their vocations either to marry or to take up an inheritance of some kind."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The registers are sure to contain other fascinating tales, according to a statement from the university. Not only have they been little studied, but the registers chronicled the day-to-day activities of archbishops, who at the time had pretty interesting lives.

"On the one hand, they carried out diplomatic work in Europe and Rome, and rubbed shoulders with the VIPs of the Middle Ages," she said in a statement. "However, they were also on the ground resolving disputes between ordinary people, inspecting priories and monasteries and correcting wayward monks and nuns."

The devout job also would have been a dangerous one, as the Black Death was sweeping through Europe at the time (from 1347 to 1351). And the priests were the ones who would visit the sick and administer last rites, she noted.

Rees Jones and her colleagues hope to find out more on some of the most compelling archbishops, including Melton, who led an army of priests and everyday residents in a battle defending the City of York from the Scots in 1319. Another archbishop, Richard le Scrope joined the so-called Northern Rising against Henry IV, for which he was executed in 1405. The records, Rees Jones said, may reveal his motivations for getting involved. [Gallery: In Search of the Grave of Richard III]

They might even uncover the rest of the story of the escapee nun and whether she was returned to the convent.

The registers themselves, tucked into 16 heavy volumes, had what the university called a "perilous existence." Officials of the medieval archbishop would have carried the parchment volumes on his travels. And after the English Civil War, in 1600s, they were stored in London, before being brought, in the 18th century, to the Diocesan Registry in York Minster.

The University of York project to put the registers online will run for 33 months in partnership with The National Archives in the United Kingdom, and with the support of the Chapter of York Minster.

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families

- In Photos: 'Demon Burials' Discovered in Poland Cemetery

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus