Photos: Craters Hidden Beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

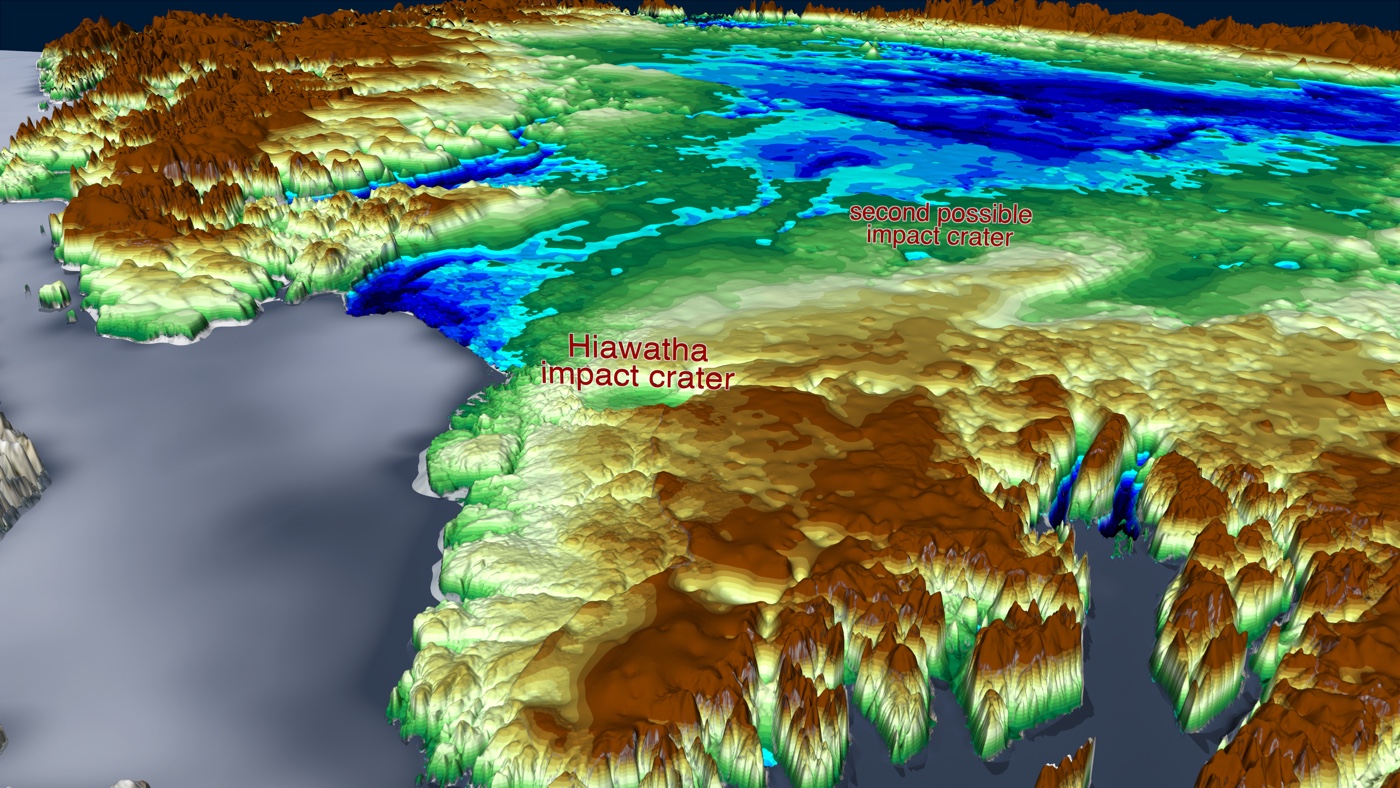

Two hidden craters

In 2018, scientists reported the discovery of the first-ever meteor impact crater under the Greenland Ice Sheet. It didn't take long for them to find another. Reporting Feb. 11, 2019, in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers led by NASA Goddard glaciologist Joseph MacGregor described a second possible impact crater just 113 miles (183 kilometers) from the first.

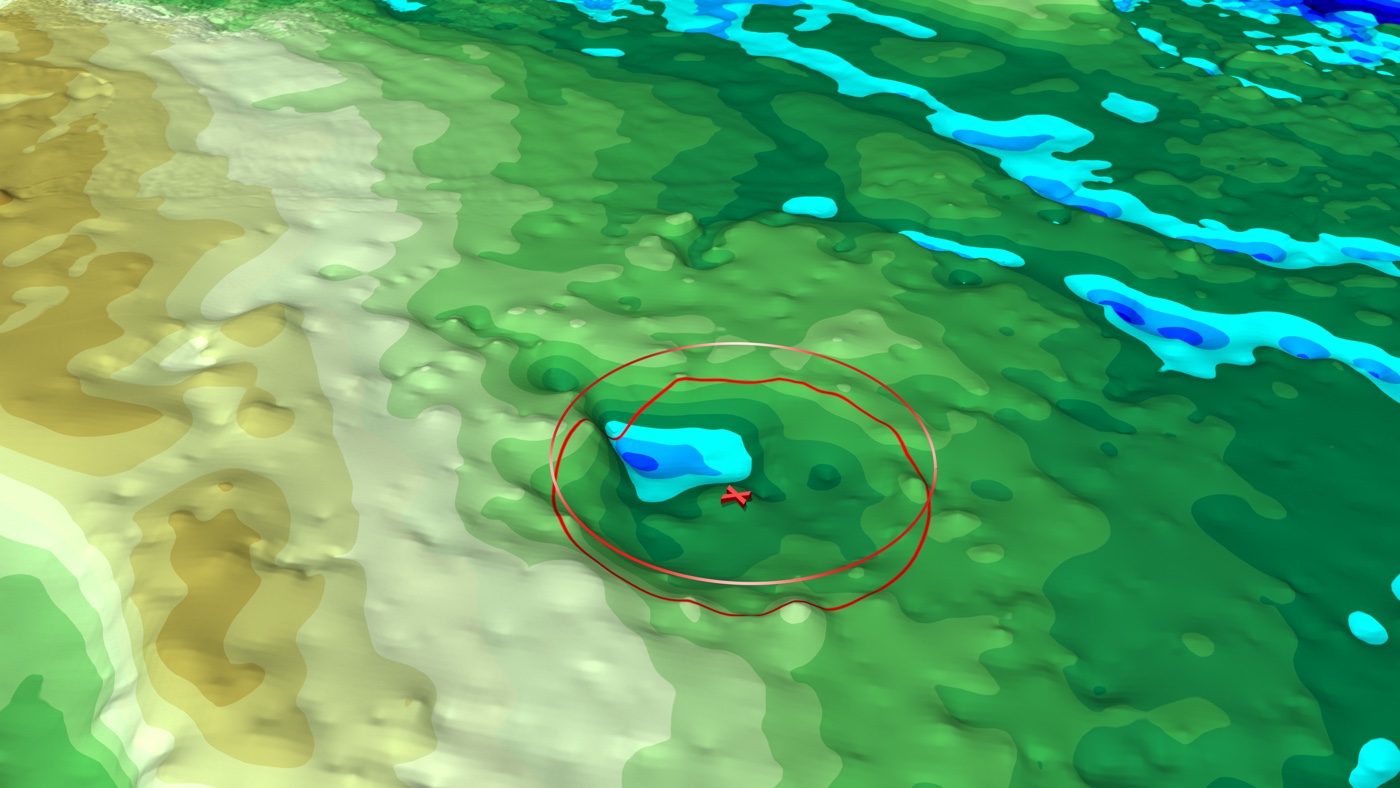

X marks the spot

The research team used a combination of satellite imagery of the ice and radar measurements of the underlying bedrock to discover the likely crater. The only other explanation for the circular depression could be a volcanic caldera, MacGregor told Live Science, but there is no sign of the magnetic anomalies that are seen in volcanic rocks. A large meteor collision is a more likely explanation, he said.

Deep depression

The newly discovered crater is a depression 22 miles (36 km) in diameter, making it the 22nd-largest impact crater ever discovered on Earth. Its previously discovered neighbor, the Hiawatha crater, is slightly smaller at 19 miles (31 km) across. The Hiawatha crater is under about a half-mile (930 meters) of ice, while the new crater is buried far deeper: 1.2 miles (2 km) down.

Dating a crater

Scientists aren't sure how old the crater is. The oldest layer of ice above it that has been dated is 79,000 years old, but ice flows, so there is no guarantee that the 79,000-year-old ice was the original ice covering the depression. An analysis of the ratio between the crater's depth and width suggests that it has been eroding for between 100,000 and 100 million years.

Hello, Hiawatha

This image shows the location of the original Hiawatha crater, which sits under the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet. It would have been formed by a meteor 0.6 miles (1 km) wide, according to a study published in November 2018 in the journal Science Advances. Scientists estimate that the Hiawatha crater is younger than the new crater, at between 12,000 and 3 million years old.

Remote location

Both craters were found in a remote region of northwest Greenland. The arrow points to the Hiawatha crater. The new crater is farther inland, buried deeper under ice and in a far more challenging area for study.

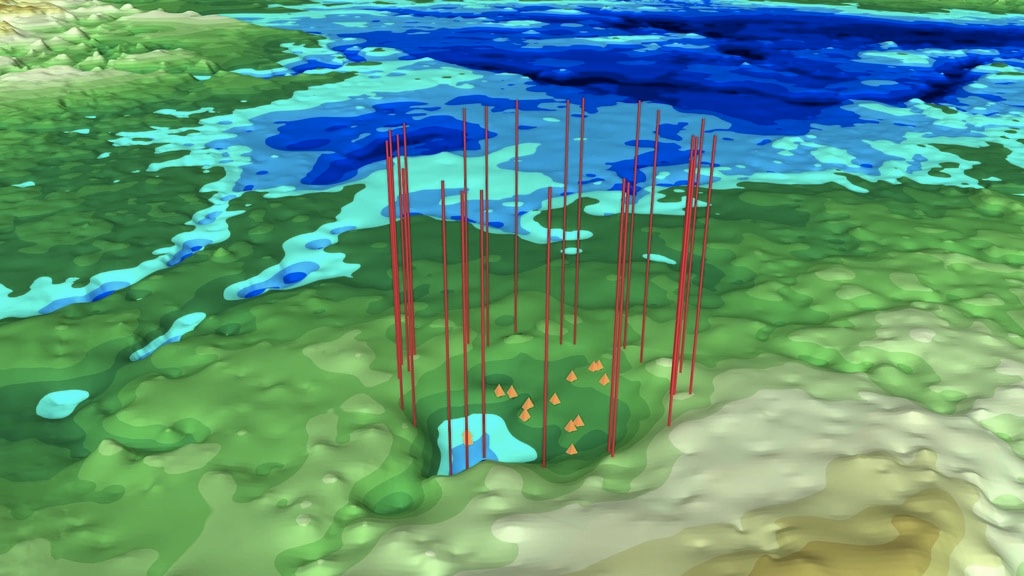

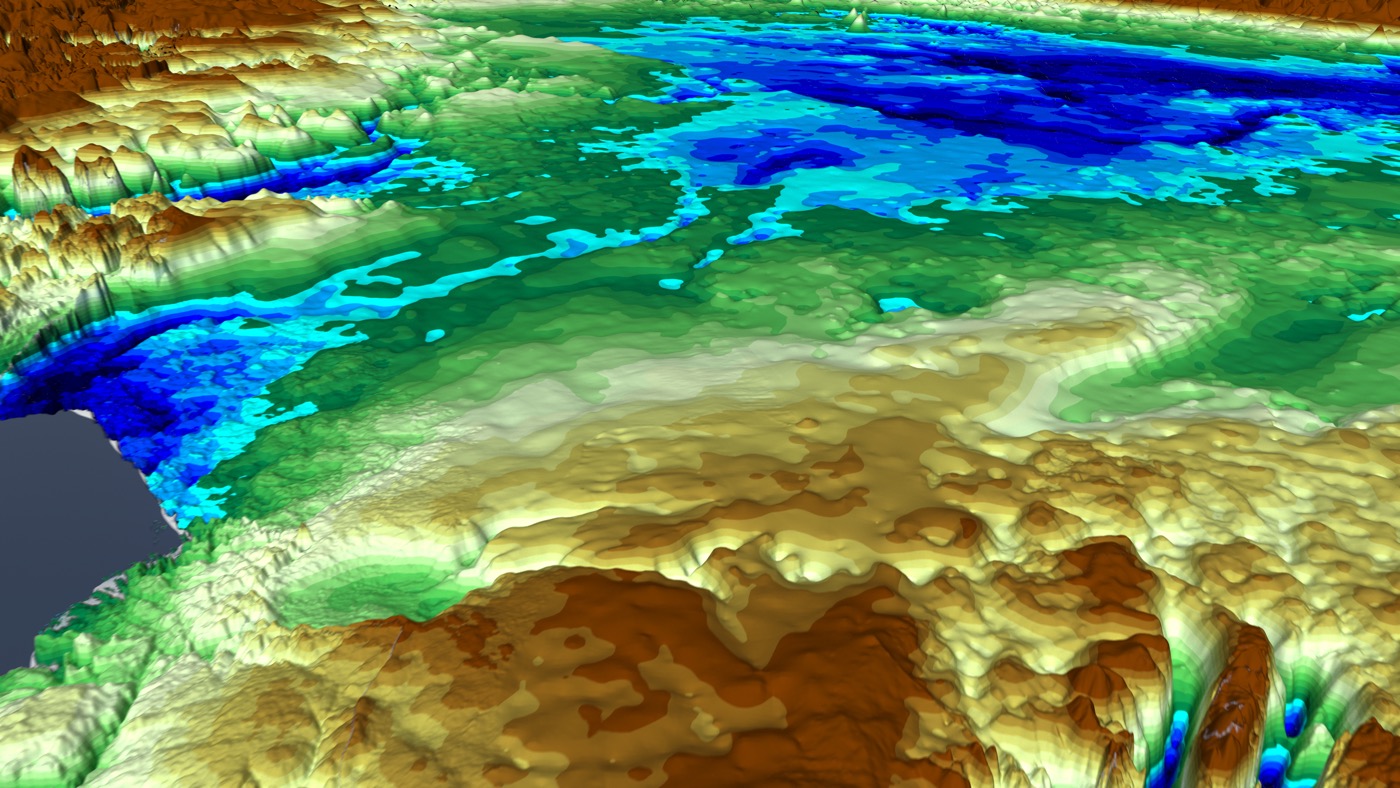

The bedrock beneath

A virtual look at the Hiawatha crater, peeling away the layers of ice on top of it. Scientists map the bedrock below the ice using radar waves beamed from an aircraft. The waves travel through the ice and bounce back to receivers on the plane. From the changes in the waves, researchers can reconstruct the shape of the underlying topography.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Strange circle

A look at the topography of the new impact crater. More craters may dot the subsurface of the Greenland Ice Sheet, MacGregor said, but the two already found are probably the largest and most obvious.

Crater questions

It was surprising to find two craters so close together, MacGregor said. Exploring the second crater would be a scientific and technical challenge, he said, given its remote location and the depth of the ice.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus