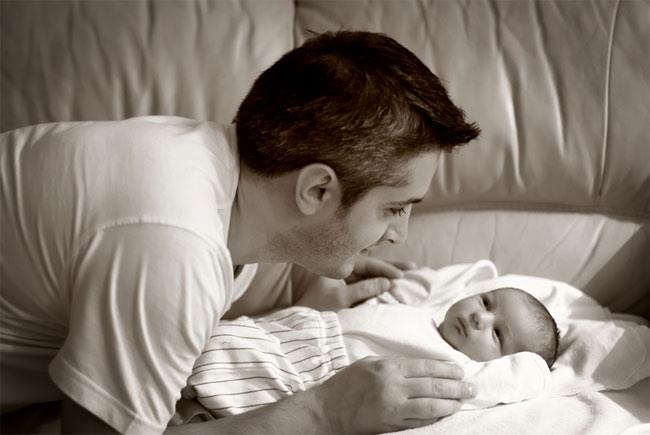

Dads Get Postpartum Depression, Too

Dads get the blues after baby is born, too.

One in 10 fathers, and one in five mothers, experience prenatal or postpartum depression, with the risks peaking when the baby is 3 to 6 months old, a new study reveals.

"Depression affects both parents and both parents should be on the lookout for it," said lead researcher James Paulson of Eastern Virginia Medical School.

The risk for both parents is highest in the United States, leading researchers to speculate that work and policy conditions — such as standard three-month maternity leaves — might contribute to the rise in parental depression at this time.

And while Dad's depression may take a different tone, with more irritable and angry behaviors, than Mom's, it is likely to be just as detrimental to the child, the researchers say.

An international analysis

While baby blues and postpartum depression are well documented in women, the new research, to be published in the May 19 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, suggests they are not alone.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Analyzing 43 studies, involving 28,004 participants, Paulson and his colleagues tracked depression in fathers from the first trimester through the first year postpartum. The researchers also searched for evidence of publication bias — where null effects go unreported — and found the data likely reflects the general population accurately.

On average the studies showed, 10.4 percent of new fathers became depressed during the gestational or postpartum period. In the subset of studies that looked at paternal well-being three to six months after the baby was born, 25.6 percent of fathers were depressed.

Both fathers and mothers in the United States were more likely to experience depression than their counterparts in Europe, Australia, South America and China, the researchers found. Paternal depression rates stood at 14.1 percent in the United States and 8.2 percent internationally.

"Three months is when family leave runs out [in the United States], and I can't help but wonder if that has something to do with it," Paulson said. "But there is also a lot going on with the child by that time."

Studies have shown that crying peaks after three months and the baby may be more demanding, having developed clear preferences for certain behaviors, such as being constantly held, he said.

Other causes of parental depression can be isolation from the outside world, sleep deprivation, changes in the couple's relationship and adjustment to the change in one's life role, Paulson said.

A family affair

"Depression in one partner has a cascading effect throughout the entire family unit," said Paulson, noting that a moderate correlation was found between depression rates in mom and dad. For clinical purposes, new parents should be understood as a couple, rather than just an individual, and the entire family should be looked at as a whole, he said.

While the effect of mom's mood on child development has been well-researched, only a few studies have looked at dad's doldrums. So far, "the findings look remarkably like the research documenting the effects of mom's depression," Paulson said.

According to one large study, following more than 10,000 families for seven years, a father's depression during his child's infancy made the kid more likely to have emotional and behavioral problems by 3.5 years old and more likely to have a psychiatric disorder by the age of 7. This remained true even if dad's depression disappeared after infancy and even after accounting for mom's depression, explained Paulson, who was not involved with this 2008 study published in The Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Further research suggests dad's depression may express itself somewhat differently than mom's. There may be more irritability, anger and withdrawal, and less sadness, than is typical of female depression. Family members should look for these behaviors as "red flags," Paulson said.

- Top 10 Controversial Psychiatric Disorders

- 10 Things Every Woman Should Know About A Man's Brain

- Kids are Depressing, Study of Parents Find

Robin Nixon is a former staff writer for Live Science. Robin graduated from Columbia University with a BA in Neuroscience and Behavior and pursued a PhD in Neural Science from New York University before shifting gears to travel and write. She worked in Indonesia, Cambodia, Jordan, Iraq and Sudan, for companies doing development work before returning to the U.S. and taking journalism classes at Harvard. She worked as a health and science journalist covering breakthroughs in neuroscience, medicine, and psychology for the lay public, and is the author of "Allergy-Free Kids; The Science-based Approach To Preventing Food Allergies," (Harper Collins, 2017). She will attend the Yale Writer’s Workshop in summer 2023.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus