New Supercomputer with 1 Million Processors Is World's Fastest Brain-Mimicking Machine

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

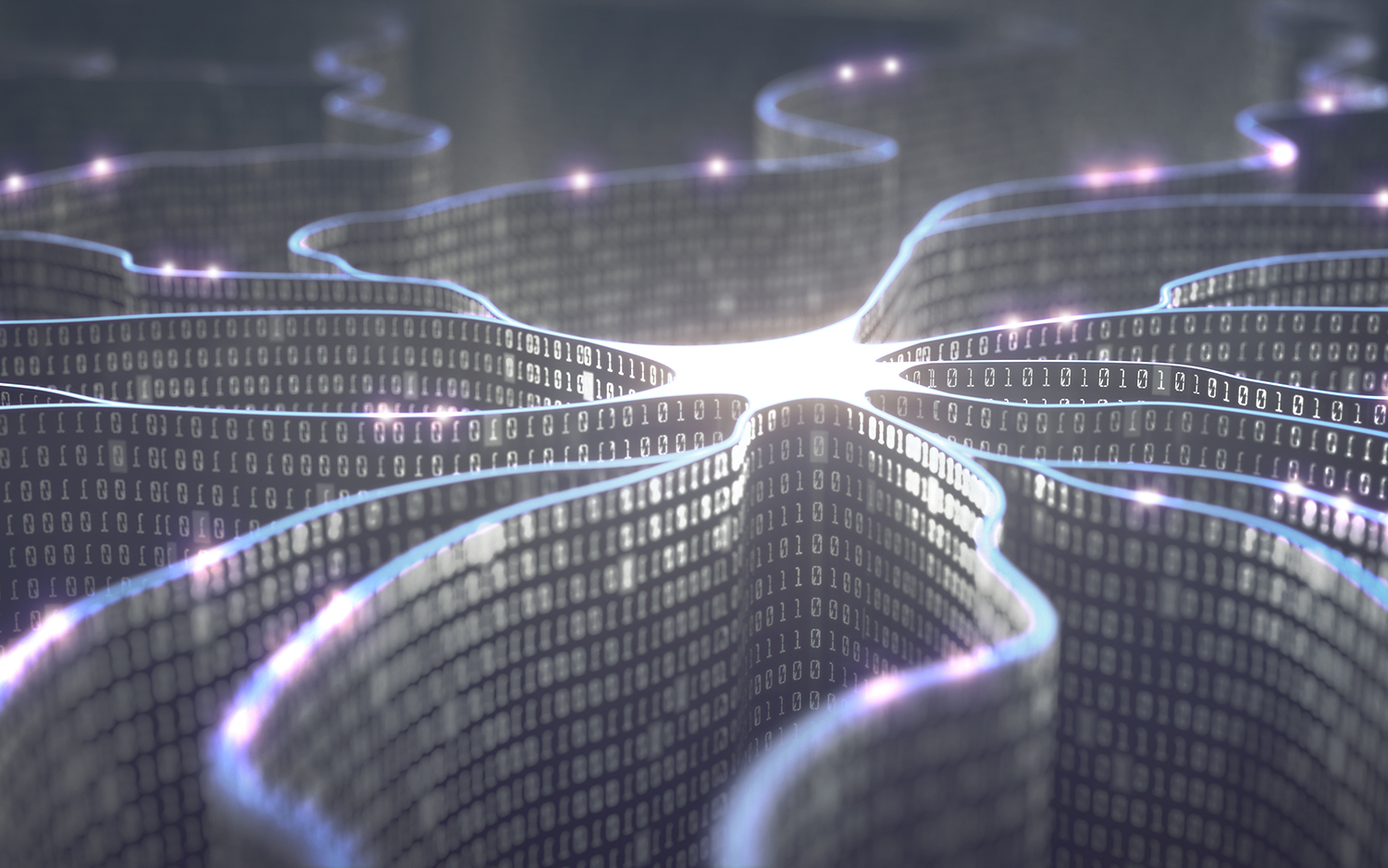

Scientists just activated the world's biggest "brain": a supercomputer with a million processing cores and 1,200 interconnected circuit boards that together operate like a human brain.

Ten years in the making, it is the world's largest neuromorphic computer — a type of computer that mimics the firing of neurons — scientists announced on Nov. 2.

Dubbed Spiking Neural Network Architecture, or SpiNNaker, the computer powerhouse is located at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, and it "rethinks the way conventional computers work," project member Steve Furber, a professor of computer engineering at the University of Manchester, said in a statement. [Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts]

But SpiNNaker doesn't just "think" like a brain. It creates models of the neurons in human brains, and it simulates more neurons in real time than any other computer on Earth, according to the statement.

"Its primary task is to support partial brain models: for example, models of cortex, of basal ganglia, or multiple regions expressed typically as networks of spiking [or firing] neurons," Furber told Live Science in an email.

Double the processors

Since April 2016, SpiNNaker has been simulating neuron activity using 500,000 core processors, but the upgraded machine has twice that capacity, Furber explained. With the support of the European Union's Human Brain Project — an effort to construct a virtual human brain — SpiNNaker will continue to enable scientists to create detailed brain models. But now it has the capacity to perform 200 quadrillion actions simultaneously, university representatives reported in the statement.

While some other computers may rival SpiNNaker in the number of processors they contain, what sets this platform apart is the infrastructure connecting those processors. In the human brain, 100 billion neurons simultaneously fire and transmit signals to thousands of destinations. SpiNNaker's architecture supports an exceptional level of communication among its processors, behaving much like a brain's neural network does, Furber explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Conventional supercomputers have connectivity mechanisms that are much less wellsuited to realtime brain modeling," he said. "SpiNNaker is, I believe, capable of modeling larger spiking neural networks in biological real time than any other machine."

Mind over matter

Previously, when SpiNNaker was operating with only 500,000 processors, it modeled 80,000 neurons in the cortex, the brain region that moderates data from the senses. Another SpiNNaker simulation of the basal ganglia, a brain area affected by Parkinson's disease, hints at the computer's potential as a tool for studying brain disorders, according to the statement.

SpiNNaker can also control a mobile robot called SpOmnibot, which uses the computer to interpret data from the robot's vision sensors and make navigation choices in real time, university representatives said.

With all its computing power and brain-like capabilities, how close is SpiNNaker to behaving like a real human brain? For now, exactly simulating a human brain is simply not possible, Furber said. An advanced machine such as SpiNNaker can still manage only a fraction of the communication performed by a human brain, and supercomputers have a long way to go before they can think for themselves, Furber wrote in the email.

"Even with a million processors, we can only approach 1 percent of the scale of the human brain, and that's with a lot of simplifying assumptions," he said.

However, SpiNNaker could mimic the function of a mouse brain, which is 1,000 times smaller than a human brain, Furber added.

"If a mouse thinks mouse-sized thoughts and all that is required is enough neurons wired together in the right structure (which is itself a debatable point), then maybe we can now reach that level of thinking in a model running on SpiNNaker," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus