Ancient Mediterranean 'Juglet' Contained Traces of Opium

A curious-looking container, discovered in the Mediterranean and dating back to more than 3,000 years ago, has been found to contain traces of opium, according to a new study from U.K. researchers.

The findings add evidence to a long-running debate about whether the containers, called "base-ring juglets," were used to carry opium.

The containers were widely traded in the eastern Mediterranean around 1650 to 1350 B.C. [Trippy Tales: The History of 8 Hallucinogens]

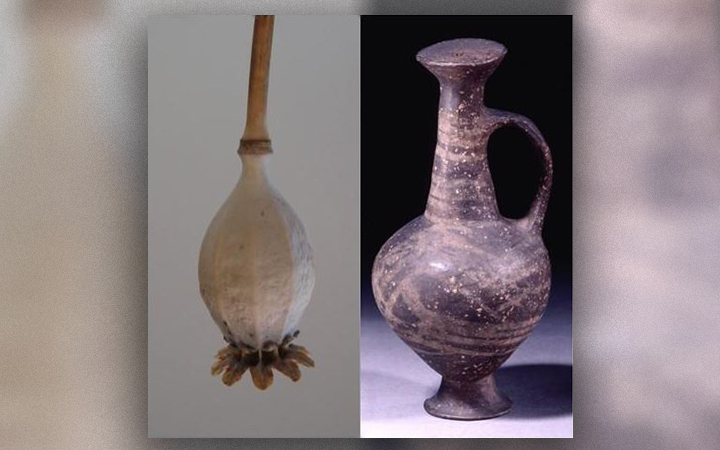

Beginning in the 1960s, some researchers hypothesized that the shape of the containers was a clue to their purpose: When inverted, they look like the seed heads of opium poppies.

But reliable evidence linking the containers to opium has been lacking.

Now, researchers from University of York and the British Museum have used a range of analytical techniques to provide the first rigorous evidence that the vessels did in fact contain opium.

The researchers studied a juglet from the British Museum. The juglet had been sealed, which allowed the contents inside to be preserved, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Initial analysis showed that the residue in the juglet was mostly composed of plant oil, but also suggested the presence of opium alkaloids, which are a group of organic compounds derived from the opium poppy. These compounds include the powerful painkillers morphine and codeine, as well as other compounds that don't have analgesic effects.

But in order to conclusively detect the opium alkaloids, the researchers needed to create a new analytical technique using instruments from University of York's Centre of Excellence in Mass Spectrometry.

"The particular opiate alkaloids we detected are ones we have shown to be the most resistant to degradation," study co-author Rachel Smith, of University of York's Department of Chemistry, said in a statement. (Smith developed the new technique as part of her doctoral thesis.) These degradation-resistant opiate alkaloids do not include morphine, Smith noted.

The researchers stress that it's still unclear exactly how the juglet was used. "Could [the opiates] have been one ingredient amongst others in an oil-based mixture, or could the juglet have been re-used for oil after the opium, or something else entirely?" Smith said.

One previous hypothesis was that the juglet could have been used to hold poppy seed oil used for anointing or in a perfume.

"It is important to remember that this is just one vessel, so the result raises lots of questions about the contents of the juglet and its purpose," said Rebecca Stacey, a senior scientist in the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research at the British Museum. "The presence of the alkaloids here is unequivocal and lends a new perspective to the debate about their significance."

The earliest evidence of opium-poppy use by humans dates to the sixth millennium B.C. (6000 to 5001 B.C.), Live Science previously reported.

The study is published yesterday (Oct. 2) in the journal Analyst, a publication of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus