Cave Divers Prevail, As All 12 Boys and Soccer Coach Are Brought to Safety

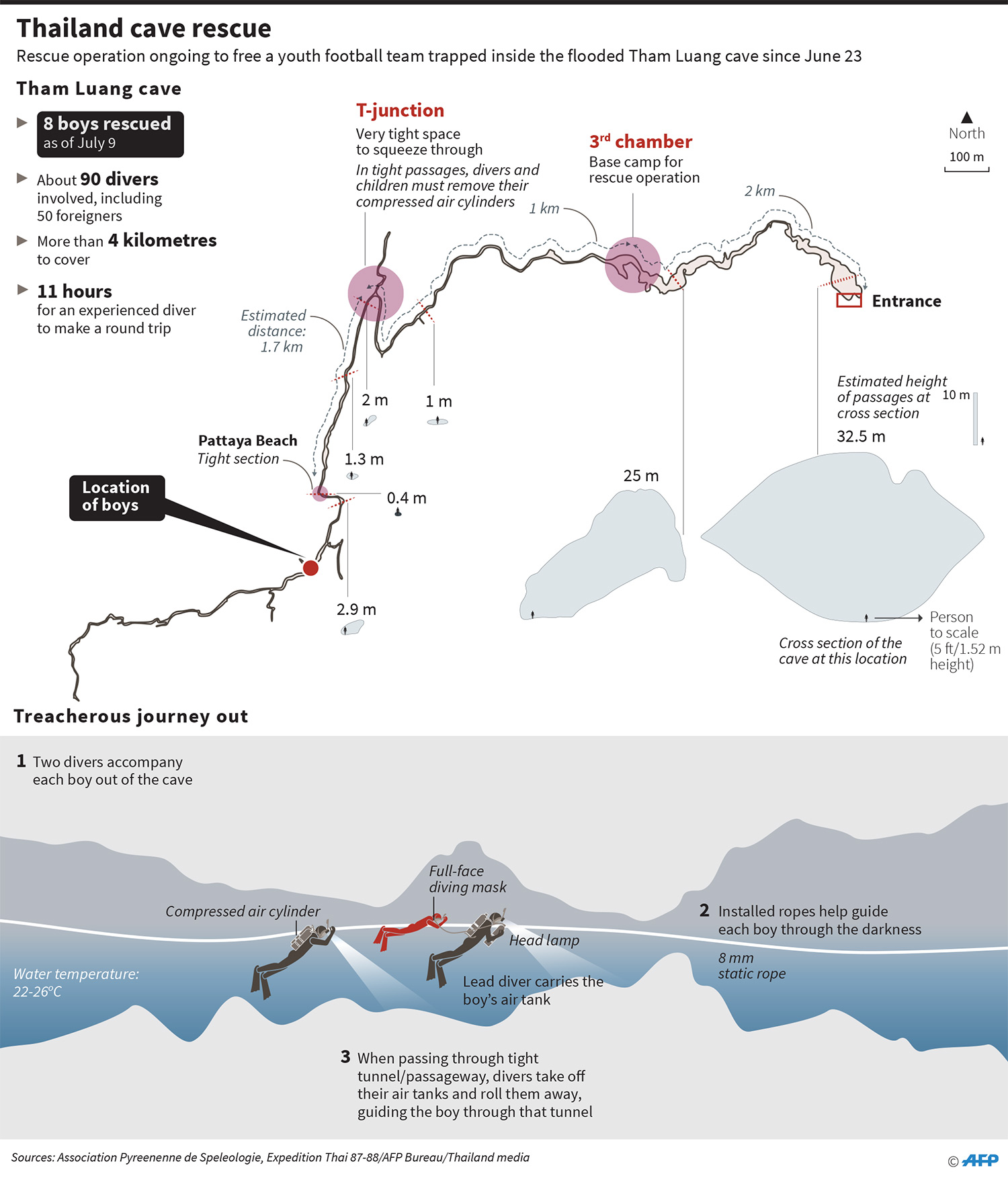

The final two have been successfully extracted from the Tham Luang cave complex in Thailand on Tuesday (July 10), where a total of 12 boys and their 25-year-old coach had been trapped since June 23. This was the third consecutive day of a risky dive rescue that started Monday morning (July 9) local time. Rescuers extracted the first four members of the soccer team on July 8 and the next four the following day.

Chiang Rai acting Gov. Narongsak Osottanakorn said today that the rescue operation had gotten quicker as the divers have become more skilled and confident, the Washington Post reported. "I do expect all of them will come out today," said Narongsak, according to the Post. Reportedly, the press center nearby erupted in cheers.

Before the rescued boys and their coach can finally be reunited with family and friends, they must stay quarantined in the hospital to ensure they didn't pick up any diseases in the cave complex. Caves, it turns out, are petri dishes for pathogens, Live Science previously reported.

Eighteen divers reportedly entered the cave Sunday morning around 10 a.m. local time. (Many more divers, nearly 100, have reportedly been helping with the rescue operation.) The fifth boy was brought out late on Monday local time, while the other three followed by evening, the Washington Post reported. Conditions were reportedly as perfect as could be expected and the mission went faster than expected, Osottanakor said on Monday, according to news reports.

Though many had said they considered a diving rescue a last resort, as the boys have no diving experience and some were malnourished and experiencing exhaustion from their time in the cave, rain began falling in the area on Saturday. Officials were concerned that monsoon rains, which were forecast over the weekend, would make such a rescue essentially impossible.

"If we don't start now, we might lose the chance," Osottanakorn said Sunday, according to news reports. As water levels rise in the cave, the distance the boys would have to dive increases. [The Very Real Risks of Rescuing the Boys Trapped in a Thai Cave]

The boys and their coach hiked into the Tham Luang cave complex when it was relatively dry, only to be walled in after monsoon rains triggered a flash flood.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This past week, water levels have been declining in the cave, as the rain has held off and officials have continued to pump water out of the cave system. As such, the first few pockets the team will need to move through are now dry, according to a report by the Washington Post, which also reported that oxygen levels have stabilized (they were falling to near-dangerous levels).

"The shorter the dive distance, the increased margin of safety," George Veni, executive director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute and president of the International Union of Speleology, told Live Science. "Also, air bells may develop along the way to create a series of two or more shorter dives instead of one long dive," Veni said, adding that "lower water levels means the force of the water is less." [Photos: Rescuers Race Against Time to Save Soccer Team Trapped in Thai Cave]

One of the big concerns with cave diving is the violently flowing water that can make a short dive risky for even an expert, said Edd Sorenson, a regional coordinator in Florida for the nonprofit International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery. (Sorenson is also the safety officer for the National Speleological Society-Cave Diving Section.)

The Thai Navy SEALS were teaching the trapped soccer team the basics of cave diving, but as recently as Friday, Gov. Osottanakorn said the kids were not adequately trained to make the risky dive out.

The team is reportedly holed up in a chamber about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) into the cave, with experienced divers taking about 11 hours up and back during delivery missions over the past week.

"Diving in caves is very risky; it's very unforgiving. If something goes wrong, you can't go up for air," Veni told Live Science earlier in the week. "In case of an emergency, you may have to swim underwater for 10 minutes and do some underwater gymnastics to get through a narrow space and get up to air."

Veni added, "You're in total darkness; essentially, you're swimming through mud."

Each of the boys, who will wear full masks, will be paired up with two trained divers, tethered to the front diver, who will also carry the boy's air tank, with the second expert diver following up in the rear, the BBC News reported.

The boys will not be diving the whole time, as parts of the cave are dry or not filled too high with water. About halfway along the 2.5-mile-long escape, the divers will need to squeeze through what is considered the toughest part of the operation, a narrow section called T-Junction in which the divers will need to take off the air tanks to make it through, according to BBC News.

A cavern beyond that junction, called Chamber 3, is now a base for the divers; there, the boys reportedly will rest before making the walk to the cave's entrance. The entire mission could take two to four days, CBS News reported.

This is an ongoing story, and Live Science will continue to update this article as news comes in on the rescue mission.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.