Waterslides Can Literally Be a Pain in the Butt

A waterslide can be a great way to cool off in the scorching heat of summer, but gliding down one comes with a hidden risk: an injured tailbone.

A new case series documents four cases of people whose tailbones were seriously hurt when they blazed down a waterslide. (The tailbone, also called the coccyx, is the triangular, bony structure at the bottom of the spine.)

But rather than dissuade people from enjoying this summer pastime, the researchers say their goal is to raise awareness of the risk so that people know what they're getting into at the waterpark. [9 Weird Ways Kids Can Get Hurt]

"I'm not advising everyone to live their life wrapped in bubble wrap, but it's important to realize that there are some risks that go along with these activities," said case report lead author Dr. Patrick Foye, a professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, where he is the director of the Coccyx Pain Center.

After coming across a few patients with waterslide-related tailbone pain at the Coccyx Pain Center, Foye and his colleagues took a deep dive to investigate the prevalence of this injury. Their research was published May 18 in The Journal of Emergency Medicine.

In a two-year period that included 217 new patients at the Coccyx Pain Center, four of them had a waterslide-related injury, Foye found. In one case, "it was somebody who just went down a waterslide that seemed to him very bumpy," Foye told Live Science. "So, he's basically going bump-bump-bump onto his tailbone all the way down."

Another patient went airborne at the bottom of a steep slide and then banged her coccyx onto the pool floor when she landed. In another case, a woman using an inflatable waterslide at home got a coccyx injury that lasted years. And, in the fourth instance, a woman who had previously hurt her coccyx experienced a new injury while sliding down a waterslide during a family vacation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tailbone treatment

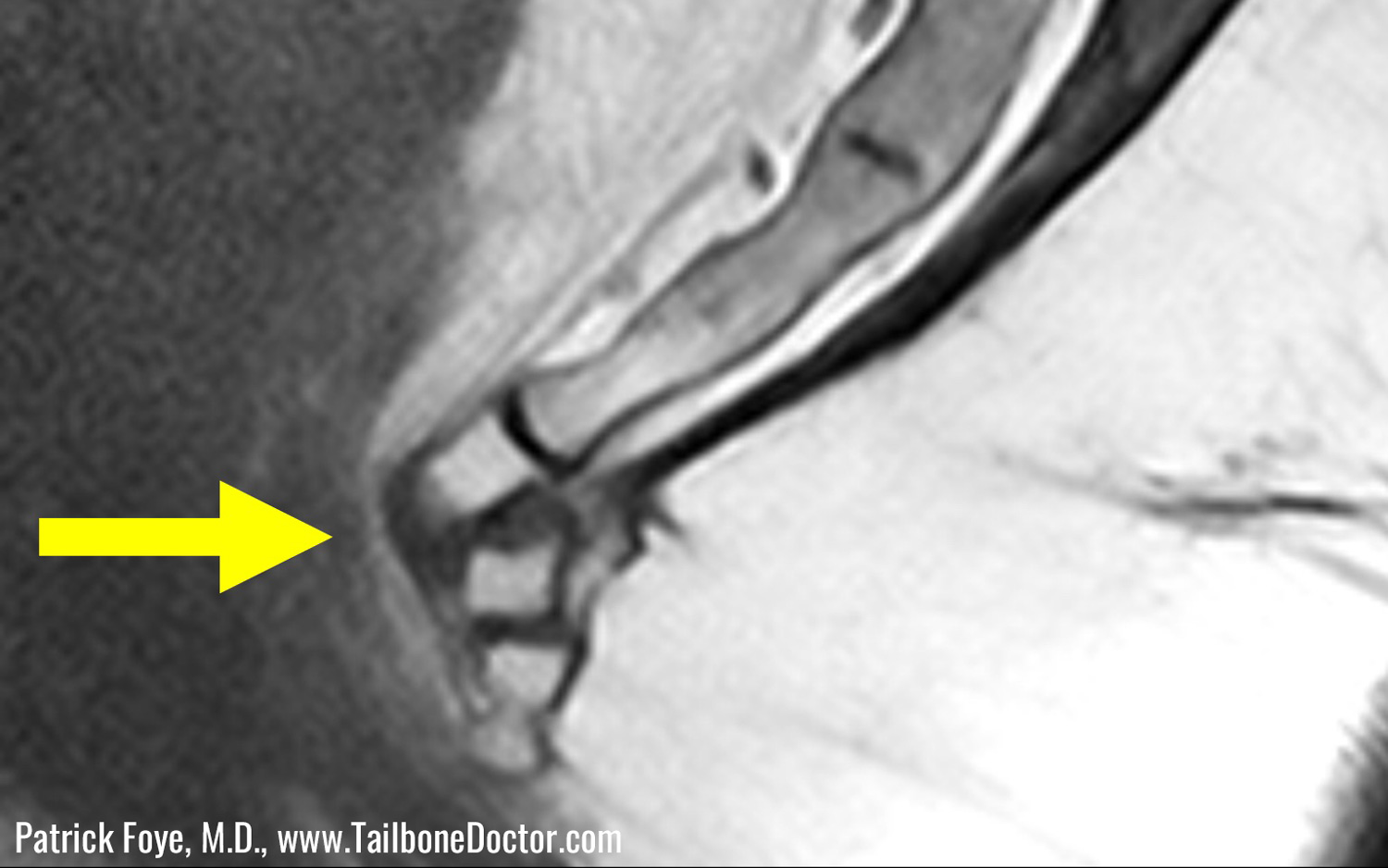

When diagnosing a tailbone injury, it's important to X-ray patients when they are sitting down, Foye said. That's because the tailbone may look normal when the person is standing, "but when they're putting their body weight onto the coccyx by sitting and leaning back, the X-rays may show a complete, 100 percent dislocation," Foye said.

He noted that tailbone injuries sometimes, but not always, lead to bruising. Often, the damage is solely internal, with no external visible signs.

Coccyx treatments vary, but Foye said that, first, he recommends that patients avoid activities that can put direct pressure on the tailbone, such as horseback riding, cycling or going down even more waterslides. People can also sit on pillows with a coccyx cutout or get a standing-up workstation.

If medical intervention is needed, patients can receive a local injection of an anesthetic or a steroid to help reduce the swelling, Foye said. Others may benefit from nerve ablation, a process in which the nerve fibers that carry the painful signals are killed or deadened.

"It's only a small minority of patients — it's probably less than 1 percent with tailbone pain — that end up needing surgery, a coccygectomy, which is essentially when they completely remove the coccyx," Foye said. Luckily, all four of the patients responded well to local injections, meaning none needed surgery, he said. However, two are still following up with him because of recurring pain.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus