Heat Shield for NASA's Next Mars Mission Breaks During Testing

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

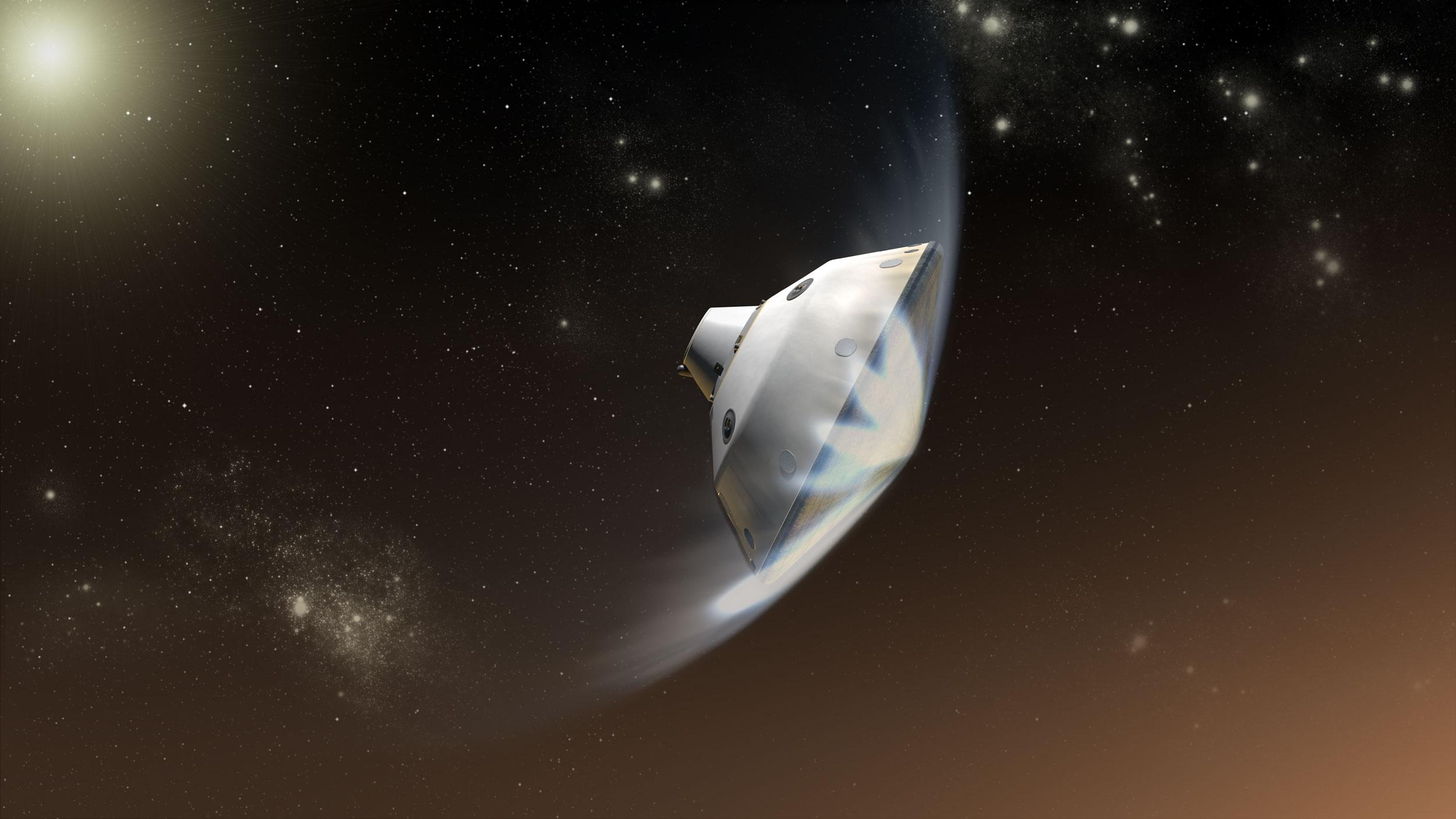

The heat shield for NASA's next Mars spacecraft just cracked open. Luckily, engineers found this out during testing here on Earth, long before the Mars 2020 rover mission leaves for the Red Planet in search of habitable environments there.

In preparation for landing, both the rover and the craft's landing gear will be encapsulated in a protective material — a heat shield — to keep them safe during the scalding trip through the Martian atmosphere.

Engineers discovered the fracture on April 12, after a week of structural testing at Lockheed Martin. The crack was unexpected, but NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory – which manages the mission development – said the mission should still lift off in 2020, as anticipated. [Interstellar Space Travel: 7 Futuristic Spacecraft to Explore the Cosmos]

The damage happened after the heat shield was subjected to forces up to 20 percent greater than what the Mars 2020 rover should encounter when it plows through Mars' atmosphere, just before landing. Engineers often test space equipment to the extreme to make sure that the devices will work under normal conditions.

"The fracture … occurred near the shield's outer edge and spans the circumference of the component," JPL said in a statement. Personnel are working "to understand the cause of the fracture and determine whether any design changes need to be incorporated into a replacement," JPL added. A replacement heat shield will be constructed, but NASA told NPR that it doesn't have an estimated cost yet. For now, scientists will repair the cracked heat shield for more prelaunch testing.

The cracked heat shield was first tested a decade ago, back in 2008. It was originally constructed as a backup shield for the successful Mars Curiosity rover. Curiosity landed on Mars in August 2012 and is now partway up a big mountain near its landing site in Gale Crater.

No cause found yet

The heat shield is made of phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator (PICA), which is a lightweight, composite material. (Mission managers try to save weight on spacecraft, since lighter spacecraft require less rocket fuel to lift the mass off Earth.) NASA also successfully flew a PICA shield on the Stardust mission, which returned samples of a comet to Earth in 2006.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Inspired by the long history of NASA's success with PICA, SpaceX created its own PICA variant for the Dragon cargo spacecraft. Dragon regularly ferries supplies to and from the International Space Station, with no major heat-shield problems so far. SpaceX is also building a version of Dragon to carry humans; the company should start test flights for it in the next year or so.

While PICA heat shields are well-tested in spaceflight, a 2013 study in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets notes that it is weak, structurally speaking.

In the study, NASA researchers performed fracture tests on charred PICA, "virgin" (unused) PICA and a precursor material called FiberForm. They were interested in figuring out the heat-shield failure on a micro scale. The precursor material was, indeed, weaker than the virgin and charred PICA. The researchers also found that the presence of a "porous matrix" in the PICA materials helps to absorb fracture energy, they wrote.

No cause is yet known for the Mars 2020 heat-shield crack. JPL struck a note of reassurance in its statement: "While the fracture was unexpected, it represents why spaceflight hardware is tested in advance so that design changes or fixes can be implemented prior to launch."

But the Mars 2020 setback also shows how hard it is to explore Mars. Many spacecraft have been lost there over the years, most recently in 2016, with the European Space Agency's ExoMars Schiaparelli test lander.

NASA's InSight lander was originally supposed to launch in 2016, but that liftoff got delayed until May 5, 2018 (if it launches on time). Mission managers found a leak in one of the main instruments for the mission, the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure.

Mars and Earth only align favorably for spacecraft launches every two years, when the planets are close enough for a spacecraft to fly to Mars without using a lot of fuel. So NASA made the choice to wait until the next Mars launch window in 2018.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus