Thousands of Mysterious Maya Structures Discovered in Guatemala

An aerial survey over northern Guatemala has turned up over 60,000 new Maya structures, including pyramids, causeways, house foundations and defensive fortifications.

It's a watershed discovery that has already led archaeologists to new sites to excavate and explore. The findings may also revise estimates of how many ancient Maya once lived in the region upward by "multiple factors," said Tom Garrison, an archaeologist who specializes in the Maya culture and is part of the consortium that funded and organized the survey. Far more ancient Maya lived on the landscape than there are people in the region today, Garrison told Live Science, and they did it without the destructive slash-and-burn agriculture that is crippling the jungle in modern times.

The finding of a sprawling Maya population shows there are means of supporting people in the area without destroying the forest, said Lisa Lucero, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois who was not involved in the new survey. [See Images of the Amazing Maya Discoveries]

Clearing the way

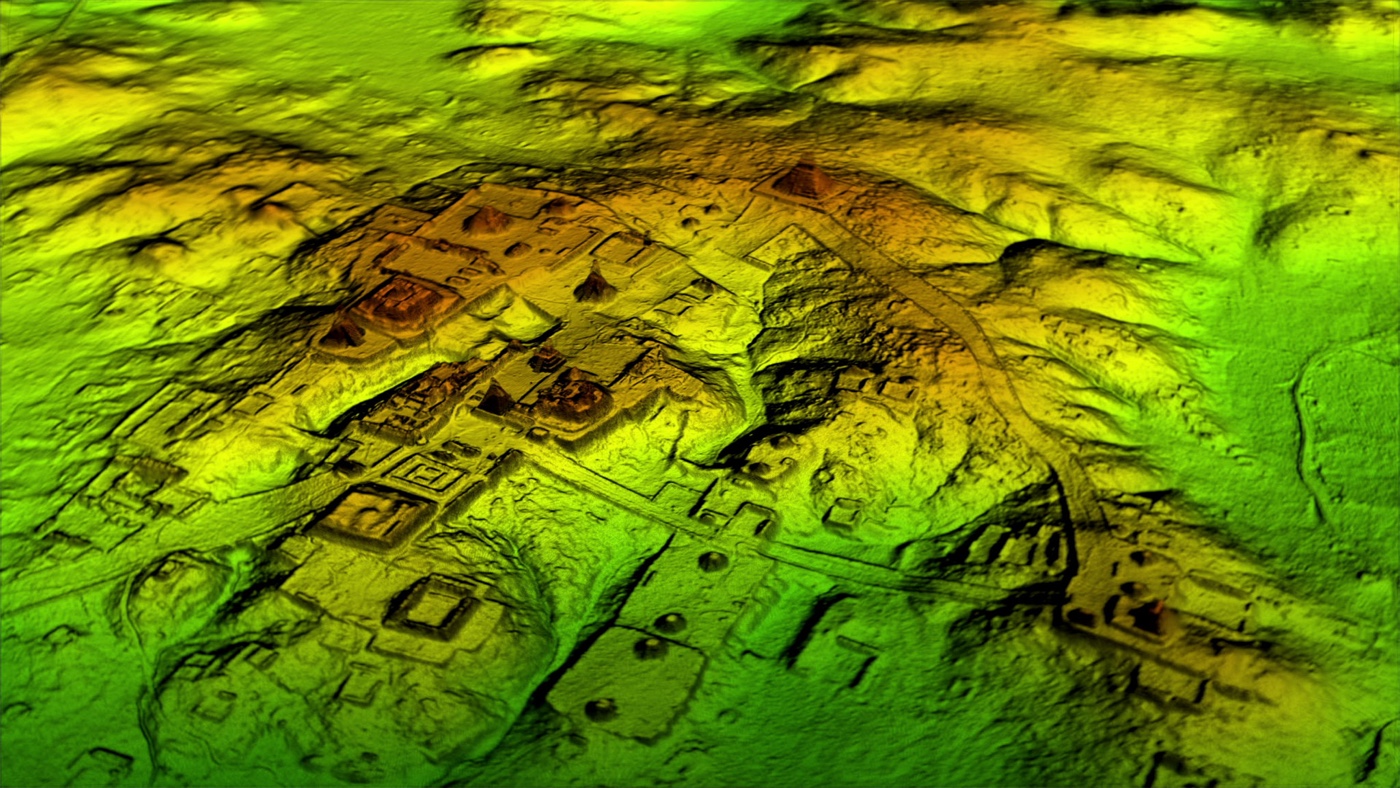

Seeing the evidence of that sprawling population requires stripping away the forest — at least virtually. The new survey used a technology called lidar, which stands for "light detection and ranging." It works by beaming laser pulses at the ground — in this case, from airplanes — and measuring the wavelengths as they bounce back to create a detailed three-dimensional image of the stuff on the ground. It's a little bit like the sonar that bats use to hunt, except it uses light waves instead of sound.

"Lidar is magic," Lucero told Live Science. In the densely forested Maya lowlands of Guatemala, it's easy to walk right by an archaeological mound or feature and miss it entirely. Lidar maps the topography with such precision that rectangular features — like roads, house foundations and plazas — just "pop out," said David Stuart, a University of Texas at Austin anthropologist who has followed the new lidar mapping project closely.

Garrison's experience bears that out. He and his colleagues have been excavating a Maya site called El Zotz in northern Guatemala, painstakingly mapping the landscape for years. The lidar survey revealed a 30-foot-long (9 meters) fortification wall that the team had never noticed before.

Related: Tikal: The iconic ancient Maya city in Guatemala

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Maybe, eventually, we would have gotten to this hilltop where this fortress is, but I was within about 150 feet [46 m] of it in 2010 and didn't see anything," he told Live Science.

Garrison visited the dirt wall in person in June, and he and his team are now seeking funding to excavate there, he said. The discovery of the fortification suggests that Maya warfare was not a matter of small, intermittent skirmishes, but serious battles.

"This is investment in the landscape," he said of the wall.

Finding hidden treasures

Lidar was first used in archaeology in 1985 in Costa Rica, but it wasn't until 2009, when researchers used it to survey a site in Belize, that it came to the region the Maya once inhabited.

Lidar "is to the 21st century what radiocarbon dating was to archaeology in the last century," said Payson Sheets, who led the Costa Rica excavation where lidar was first deployed. "It's revolutionary," said Sheets, who is a Mesoamerica anthropologist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The new effort was led by Guatemala's PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative and was funded by the PACUNAM Foundation. Aerial surveys scanned 810 square miles (2,100 square kilometers) over 10 separate areas of northern Guatemala, some of which had been mapped by hand and some of which were largely unexplored. They found more than 60,000 architectural mound structures. Most, Garrison said, are probably stone platforms that supported the pole-and-thatch homes of average Maya people. But the surveys also turned up features that are probably pyramids, causeways and defenses.

A National Geographic special, "Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings," will focus on some of these finds, including a seven-story pyramid so covered in vegetation that it practically melts into the jungle. The documentary premieres Tuesday, Feb. 6 at 9 p.m. EST/8 p.m. CST.

One intriguing feature on the lidar maps, Lucero said, is how many roads the Maya built. They did not use beasts of burden, she said, so these roads wouldn't have served as pathways for carts or wagons. They may have functioned as causeways during the swampy rainy season, she said, or as platforms for processions.

Also fascinating, Stuart said, are the blank spots on the lidar — the places the Maya chose not to live. No one wants to survey a blank area, he said, but the Maya were sophisticated users of the landscape, and their choices about where to settle might reveal more about how they farmed and used water.

"It's going to change our views of population and just on how the Maya lived on that landscape," Stuart said. "By having this more accurate picture of what is there, we can start to talk about community organization, agricultural systems land use, roadways and communication."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.