Cutting-Edge Camera Deciphers Messages Written on Mummy Wrappings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 2,000 years ago, ancient Egyptians made homemade wrappings for mummies from "recycled" scraps of paper that people had first used to scribble down shopping lists and personal notes.

Scientists have tried a wide array of methods — many of them destructive — to try to first peel apart these papyri and then decipher the ancient writings on them. Now, in an effort to analyze the papyri without destroying them, researchers have used a high-tech camera to photograph the artifacts and study their text.

The camera is remarkably effective; it can noninvasively detect the famous "Egyptian blue," carbon-based pigment and other inks containing iron, said Adam Gibson, a professor of medical physics at University College London (UCL). [Image Gallery: Egypt's Valley of the Kings]

Making a mummy

In ancient Egypt, mummies were embalmed and then wrapped in fabric bandages. Then, they were covered with cartonnage, a paper-mache material made from recycled papyri and sometimes fabric, Gibson said. Once the cartonnage hardened and was covered with plaster, artisans painted it.

Egyptians created papyri from reeds that grew in marshy areas surrounding the Nile River. Ancient people would use the resulting papyri to write notes about everyday life, including shopping lists, taxes, political notes and land surveys, according to previous analyses of mummy cartonnage made up of the notes, Gibson said.

Typically, Egyptian artifacts, such as statues, inscriptions and weapons, tell researchers about the lives of officials and royalty. In contrast, the papyri in the cartonnage offers a rare window into the lives of ordinary Egyptians, Gibson said."This is how we get information about normal people, rather than the rulers," Gibson told Live Science.

Digital scrutiny

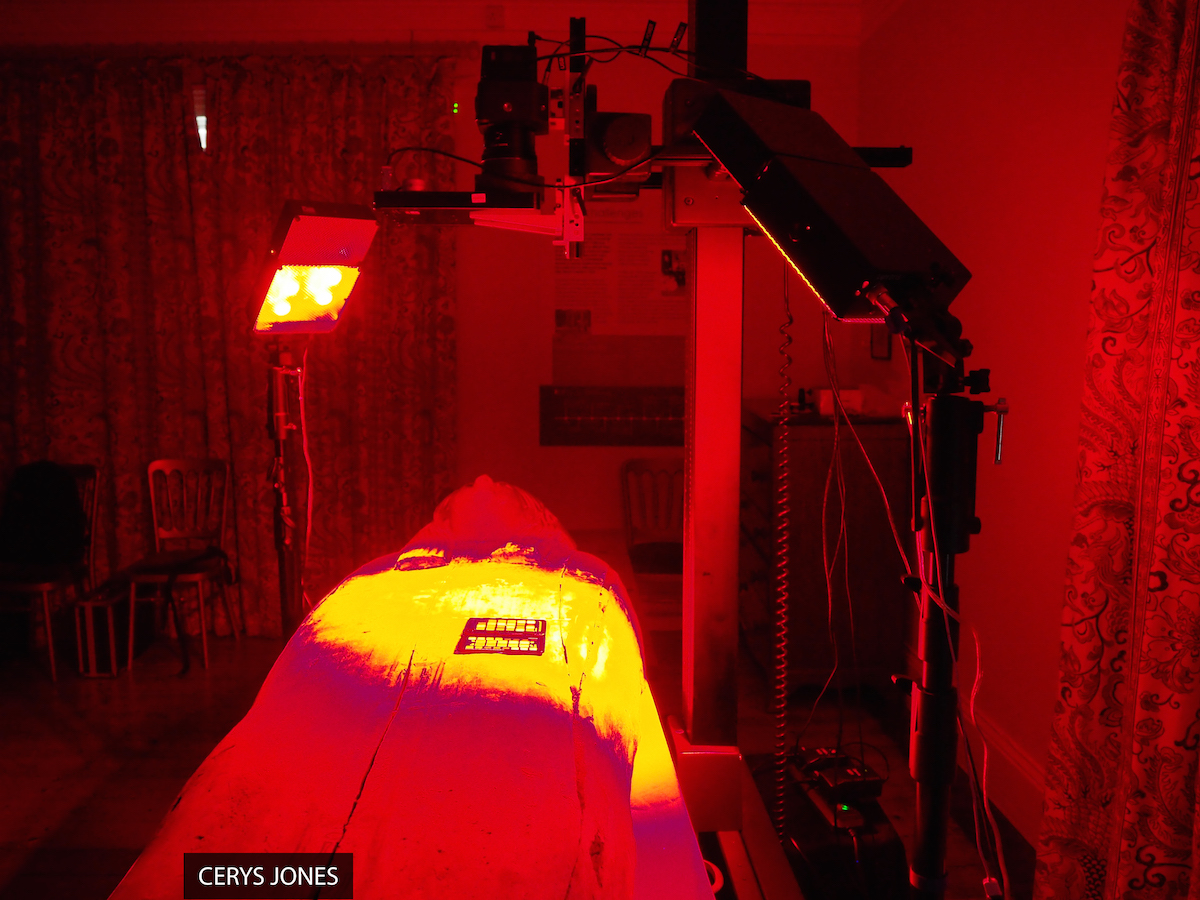

The researchers photographed different pieces of cartonnage with a camera known as a multispectral imaging system. Most cameras can detect three different wavelengths (red, green and blue), but this system can detect 12 wavelengths from 370 to 940 nanometers, ranging from ultraviolet to infrared light (visible light extends from 390 to 700 nm), said Gibson, who co-led the research with Melissa Terras, an honorary professor at the UCL Centre for Digital Humanities.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That's useful, because different inks or dyes respond differently to different wavelengths, which is why we perceive them as different colors," Gibson said.

Moreover, some of the dyes fluoresce. "If you shine blue light on them, they might glow green or red," Gibson said.

Many of the 2,500- to 1,800-year-old papyrus notes are written in demotic, a script used in ancient Egypt, typically for writing business and literary documents. However, the researchers still have to find someone to translate the pieces of cartonnage they imaged, Gibson said.

In the meantime, the team, including UCL researchers Kathryn Piquette and Cerys Jones, applied the imaging technique to another Egyptian artifact: a coffin that dates to between 664 B.C. and A.D. 30, which is on display at a museum at Chiddingstone Castle, in the United Kingdom.

The images revealed the name Irethorru on the footplate of the coffin — something that was invisible to the naked eye. Irethorru was a common name in ancient Egypt, and means "the eye of Horus is against them." Horus is the deity Egyptians depicted as a falcon-headed man, Gibson said.

The new technique may help Egyptologists analyze all kinds of Egyptian artifacts without damaging them, he noted. "You can find some horrific videos on YouTube of people taking 2,000-year-old papyrus and laughing as they destroy it in order to read the text that's inside it," Gibson said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus