Pioneers of the American West: The Harvey Girls (Photos)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Moving across the land

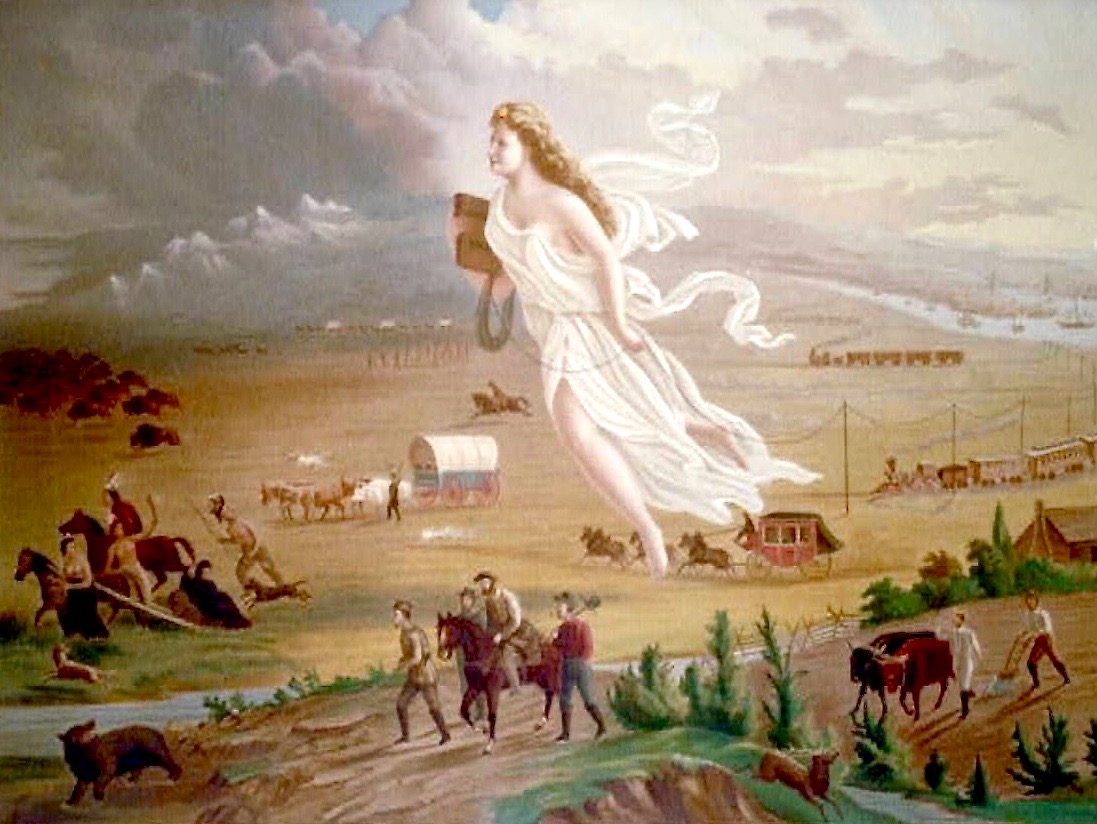

When New York Tribune owner Horace Greeley wrote in an 1865 editorial, "Go West, young man, go West," he became a leading voice in America's expansion westward following the recent successful conclusion of the long American Civil War. The age of manifest destiny had begun and war-weary Americans listened to the call, packed up their often meager belongings and began their journey to create a new western life. Pop culture, including artist like John Gast with his famous 1872 painting "American Progress," shown here, embraced this movement as thousands of miners, farmers, ex- soldiers, merchants and eventually wives followed Greeley's call.

Dangers everywhere

The trip to the West was full of peril. The railroad became one of the safest ways to travel, but riding the early trains was certainly challenging. Cars were hot, seats uncomfortable, and the food was available only at the nearby roadhouses when the steam locomotive stopped to take on water. This food was best described as "horrible" with often spoiled meats, cold beans and weak, watered-down coffee. Prices were also unusually high. The train trip from New York to California could take up to a week, and these poor conditions discouraged many train passengers from making the journey to the West.

Feeding the travelers

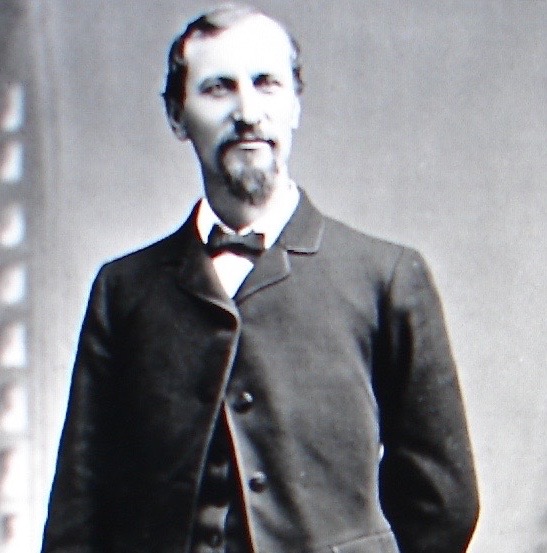

In 1876, a railroad freight agent named Fred Harvey saw a business opportunity to address the issue of poor food for the train passengers. He began a business partnership with America's largest railroad company, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, to create the first national chain of restaurants, retail stores and hotels within the railroad's train stations. Harvey became the founding father of the American hospitality industry, as he soon established some 84 Harvey Houses in cities large and small from Chicago to Los Angeles. Locating and retaining reliable and qualified employees was Harvey's biggest challenge in many Western towns along the line; he solved this problem by employing a group of young women who became known in history as the Harvey Girls.

In search of servers

Through the newspapers of the Midwest and East Coast, Harvey ran employment ads - "Wanted: Young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good moral character, attractive and intelligent, to waitress in Harvey Eating Houses on the Sante Fe in the West. Wages, $17.50 per month with room and board. Liberal tips customary. Experience not necessary. Write Fred Harvey, Union Depot, Kansas City, Missouri." Thousands applied. Those women chosen for an interview were invited to the company’s headquarters in Kansas City, Kansas. Exemplary character was the highest employment expectation and each girl hired was required to sign a pledge swearing to that fact. They also had to be well-mannered and educated at least through the eighth grade.

Working women

Harvey demanded that his restaurants provide exceptional dining to railroad passengers with the highest standards of the time in food preparation and service. His all female waitstaff, the Harvey Girls, became America's first national corp of adventurous, bright and independent working women. The reputation of a Harvey House was very important and these girls were not referred to as a "waitress" but called Harvey Girls to instill a sense of pride in the young women selected.

High expectations

Each selected girl was placed into a six-week training program. They agreed to worked 12-hour shifts six days a week, lived in dormitories with house matrons and curfews, and signed six-month contracts stipulating that they would remain unmarried. They were highly trained in rules of etiquette. They learned how to properly set a table and to be sure that none of the uniquely designed Harvey plates and glasses were cracked or chipped. They could not speak to another Harvey Girl in the presence of a customer and all Harvey Girls had to learned to always work with a sincere smile.

On the job

When her training was complete, a Harvey Girl was assigned to a Harvey House along the Santa Fe line. Most newly trained girls were assigned first to one of the smaller Harvey Houses to perfect her training before moving on to the busier houses in the larger railroad communities. All Harvey Girls were to dress in the company's uniform, which consisted of a black dress, crisp white pinafore apron, polished black shoes, black hose and a white ribbon in their hair. No make-up was allowed. All the girls were inspected to ensure their proper dress before they were allowed on the floor to serve customers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Attention to detail

Harvey was a stickler for details. He was known to flip out over an improperly set dining table demanding it be correctly set. There were many sets of rules and regulations, called the "Fred Harvey way," outlining how almost everything could be done perfectly. Male Harvey House managers followed an elaborate and detailed plan for keeping track of every egg, cup of coffee, steak, cigar, etc., sold at their Harvey House. Managers knew how many passengers were on each train and which of them intended to eat at the upcoming Harvey House. The train's whistle would blow a mile outside of town, allowing the Harvey Girls to know when another group of hungry customers were about to arrive.

Finding love

The Harvey Girls not only brought great food and fine dining etiquette to the American West, but they also brought love. During their time of employment, the girls were strictly forbidden to fraternize with the Harvey House guests. But some historians estimate that out of the over 100,000 girls who worked in the Harvey House restaurants and hotels along the rail line, some 20,000 became the wives of their regular town customers.

One railroad owner said, "The Harvey House was not only a good place to eat; it was the Cupid of the Rails." American Humorist Will Rogers said of the Harvey Girls that they "kept the West in food and wives." The photo above is of Harvey Girl Mary Lawler, who began working in the New Mexico and Arizona Harvey Houses in 1893.

Sharing a culture

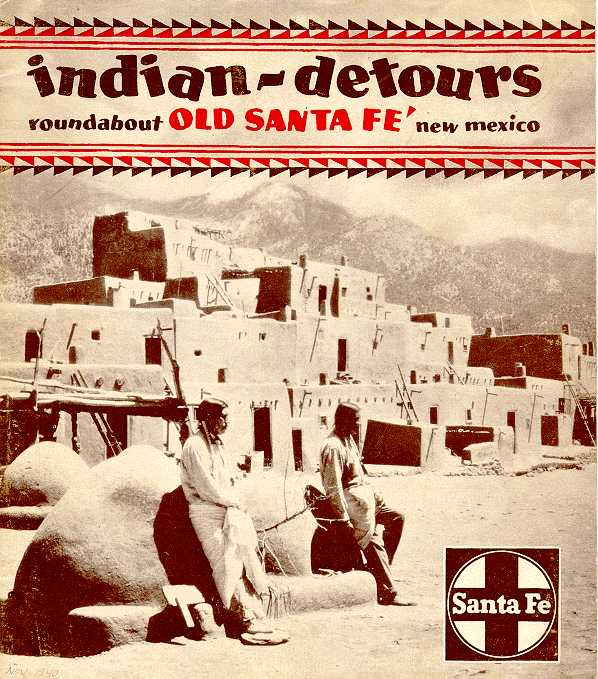

By 1902, train travel to the American Southwest was waning. The Fred Harvey Company came up with the idea to create an "Indian Department," which commissioned Native American artists, photographers and ethnographers to document and share the unique culture of the Southwest Indian tribes. In 1926, the company began their soon-to-be famous Indian Detours from their Harvey House locations between the Grand Canyon and Santa Fe. Tourists were whisked away from the Harvey Hotels by a fleet of "Harveycars" composed of the latest Franklins, Packards, Cadillacs and White Motor Co. buses. The drivers were always men, but the "couriers" or tour guides were always college-educated women trained in Southwest history and archaeology, who dressed in Navajo-style costumes that included velveteen blouses and skirts, squash blossom necklaces and concha belts. Once again, the Fred Harvey Company was the industry leader in providing quality jobs for the woman of the American West.

Serving the troops

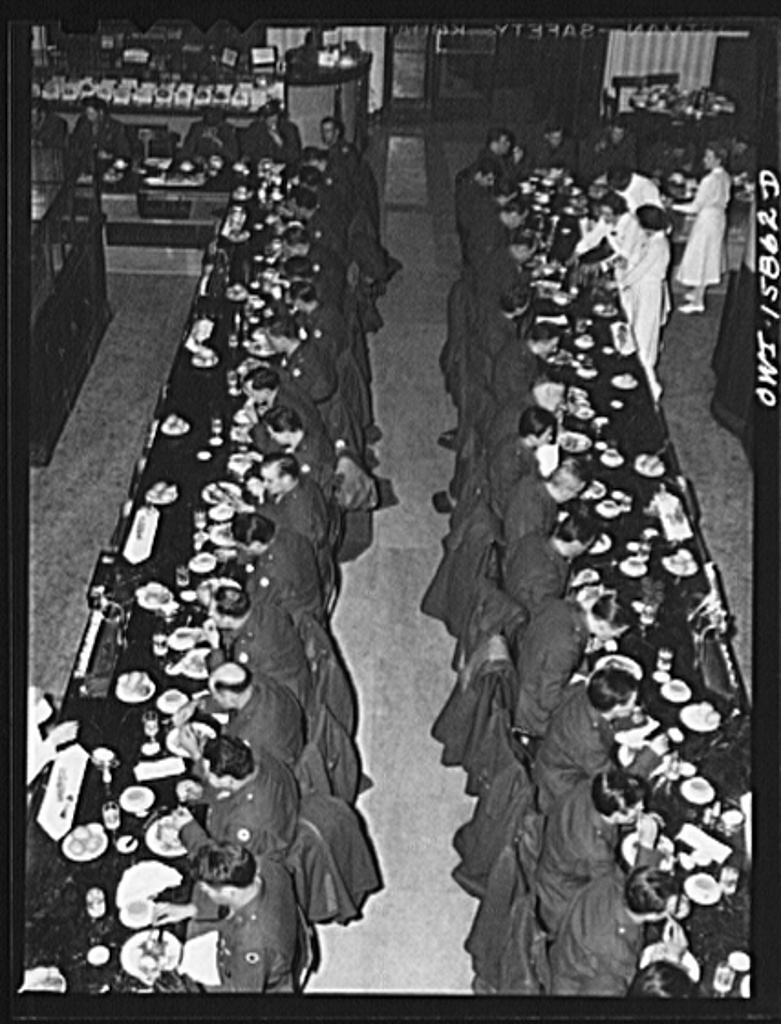

The Harvey Girls and their many Harvey Houses played an important role for American soldiers during World War II. American railroads were the main means of transporting troops from their bases of training to the West Coast for deployment into the Pacific Theatre. Records from La Posada, the spectacular Harvey House still operating in Winslow, Arizona, show that during World War II over 3,000 meals were served at La Posada daily by Harvey Girls to American soldiers as the "troop trains" made their final stop before reaching California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus