Scientists Levitate Water Droplets, Figure Out What Drives 'Magical' Behavior

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Even as physicists use big, expensive experiments to uncover huge gravitational waves and tiny hadrons, they can still answer questions about the thoroughly mundane. For example — Why do droplets of cold milk bounce on the surface of hot coffee before sinking? Why do teensy spheres of water skitter across the surface of a pool in the rain?

A team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has for the first time observed and described the forces that cause drops of liquid to levitate above the surface of larger reservoirs. [Liquid Sculptures: Dazzling Photographs of Falling Water]

Here's how it works.

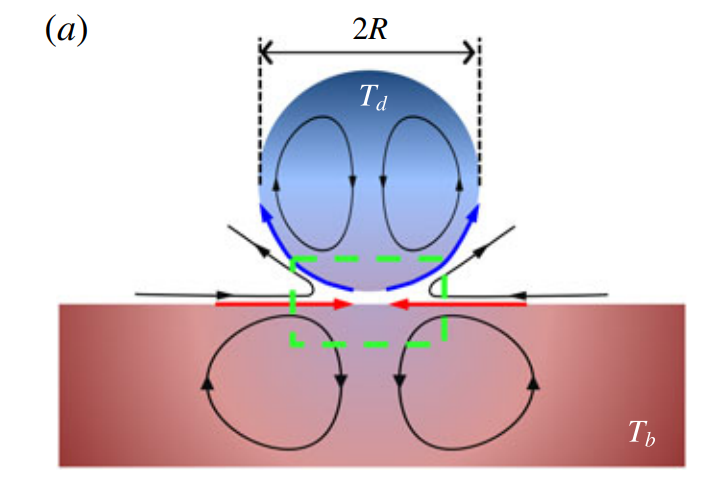

When a raindrop crashes into the surface of a puddle, the researchers found, twin engines kick in. The collision causes tiny currents to spin around inside the droplet as well as below the surface of the puddle. If you could peer into the droplet, you'd see water rushing downward along the edges inside the drop and then climbing back up toward the center, the new research found.

That spinning motion inside the droplet, invisible under most circumstances, creates enough force to tug on the air surrounding the droplet. The air forms into a thin, fast stream of wind that flows under the drop, holding it a hair's width above the surface, according to the new findings.

The researchers found, however, that those engines — inside the droplet and below the surface of the liquid — don't spin on their own. Heat differences between a drop and the liquid it impacts drive the rotation and the levitation. Once the raindrop warms or cools to the temperature of the puddle — a process sped up by those spinning engines that can take anywhere from milliseconds to seconds — it will crash through its magic rug of air and disappear into the puddle, the study showed.

The MIT researchers figured out how to calculate the minimum difference in heat for levitation to occur in any given liquid. If the difference is greater than that minimum, they found, the droplet levitates longer. Any shorter, and the drop won't levitate at all.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

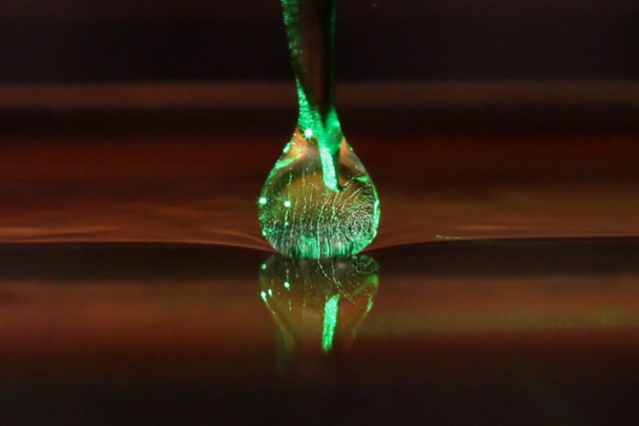

Through some clever experimental setups and the aid of high-speed cameras, the researchers were able to make some beautiful videos of the levitation engines in action. The scientists mixed some shiny flakes of titanium dioxide into oil, then pinned a drop of that oil against the surface of a larger pool with a syringe. They backlit the drop with a bright LED, and the titanium dioxide lit up as it swirled in the churning currents, following the path of the engines.

The authors published a paper describing the discovery on Nov. 8 in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus