4,000-Year-Old Prenup Mentions Infertility, Surrogacy and Divorce

Kim Kardashian made headlines recently for using a surrogate to carry her unborn child, but the practice of surrogacy — albeit in a different form — is much, much older, dating back at least 4,000 years, a new study finds.

Surrogacy in modern times often refers to the practice of a fertilized embryo from a couple being implanted and carried to term in another woman's womb. But, thousands of years ago, it took a different form.

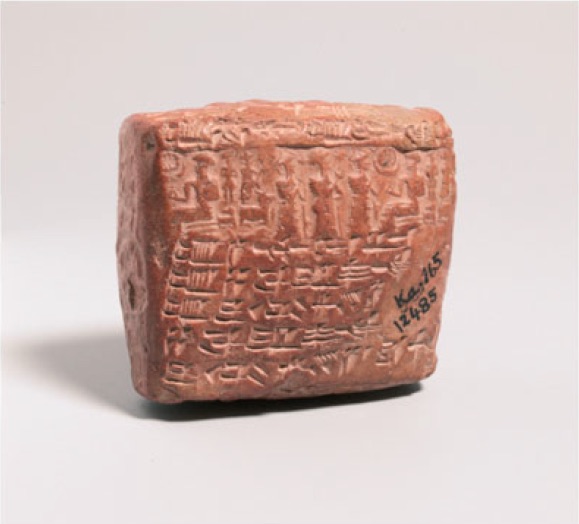

Researchers discovered the ancient evidence of surrogacy while studying an Assyrian clay tablet that contains the oldest known marriage contract with language on infertility and surrogacy. The contract details how a man named Laqipum and his bride, Hatala, will move forward with surrogacy if they don't have a child within two years. [13 Facts on the History of Marriage]

"There are many different ways to solve infertility problems — like surrogacy, as mentioned even 4,000 years ago in this Assyrian clay tablet," the researchers wrote in the study.

The tablet, as translated from cuneiform, says that if Hatala is unable to have a child, she will buy a slave woman, known as a hierodule, to sleep with her husband.

Here is the translation:

"Laqipum has married Hatala, daughter of Enishru. In the country [Central Anatolia], Laqipum may not marry another [woman], [but] in the city [of Ashur] he may marry a hierodule. If, within two years, she [Hatala] does not provide him with offspring, she herself will purchase a slave woman, and later, after she will have produced a child by him, he may then dispose of her by sale where-so-ever he pleases."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Note that the marriage contract assumes that any potential infertility stems from Hatala, the woman, rather than her husband. Granted, there wasn't an advanced scientific understanding of infertility in 2000 B.C. But now, it's well known that men can experience infertility problems, too, including from low sperm count and chronic health issues, such as obesity, Live Science previously reported.

Despite this ancient misconception, the marriage contract shows that "the concept of infertility is not just a disease of our age," but rather one of the ages, the researchers wrote in the study. Infertility and surrogacy are also mentioned in the Old Testament, including when Sarah was unable to have children in her old age, prompting her to ask Abraham to sleep with Hagar, an Egyptian slave.

"Since Hagar agreed to give birth to a baby on behalf of Sarah, we can define Hagar as a surrogate mother," Liubov Ben-Nun, a professor emeritus at the Joyce and Irving Goldman Medical School of Ben-Gurion University, in Israel, told The Times of Israel.

The marriage contract also details stipulations in the event of divorce, in case things didn't work out for Laqipum and Hatala.

"Should Laqipum choose to divorce her, he must pay [her] five minas of silver – and should Hatala choose to divorce him, she must pay [him] five minas of silver," according to a translation of the contract. (A mina is a unit of weight used for currency purposes.)

Researchers found the Assyrian tablet in modern-day Turkey at Kültepe-Kanesh, an archaeological site on the World Heritage list kept by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Archaeologists have found more than 23,500 clay tablets and envelopes, known as the Cappadocian tablets, to date. This particular tablet is on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, in Turkey.

The study was published online Oct. 26 in the journal Gynecological Endocrinology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus