Newfound Tusk Belonged to One of the Last Surviving Mammoths in Alaska

A prehistoric campfire and a number of archaeological treasures — including a large tusk of a mammoth, and tools fashioned out of stone and ivory — remained hidden for thousands of years in the Alaskan wilderness until researchers discovered them recently.

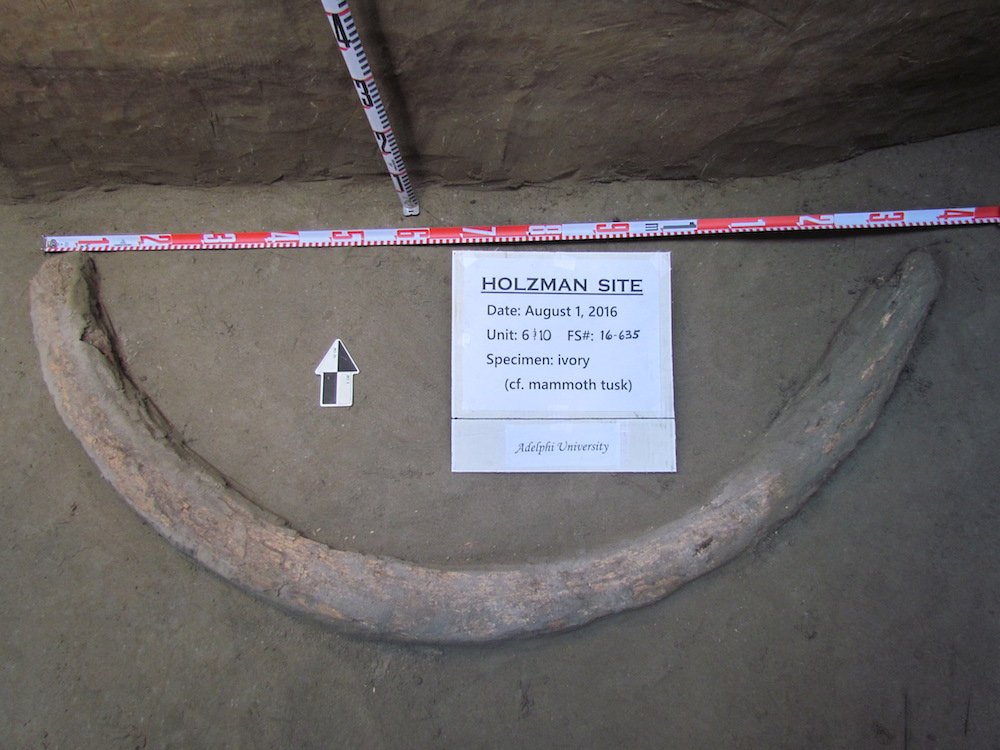

Researchers found the 55-inch-long (140 centimeters) mammoth tusk, the largest ever found at a prehistoric site in the state, during a 2016 excavation at the Holzman site, located about 70 miles (110 kilometers) southeast of Fairbanks, Alaska. A radiocarbon dating analysis revealed that the tusk was about 14,000 years old, the researchers told Live Science in an email.

"The radiocarbon dates on this mammoth place it as one of the last surviving mammoths on the mainland," Kathryn Krasinski, a co-principal investigator of the excavation and an adjunct faculty member in the anthropology department at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York, told Live Science in the email. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

The research team found the tusk in soil deposits about 5 feet (1.5 meters) underground. Though other sites have ivory fragments, this discovery marks only the second time that researchers have uncovered an entire mammoth tusk from an archaeological site in Alaska, the researchers said.

The findings suggest that the earliest documented people in Alaska likely went out of their way to acquire mammoth ivory, and that they were creating tools with the material, the researchers said.

The team plans to investigate whether prehistoric people obtained the tusk through hunting or whether it was scavenged by humans who happened to live at the site a few hundred years later, said Krasinski and her colleague Brian Wygal, a co-principal investigator of the excavation and an associate professor of anthropology at Adelphi University. The other two co-principal investigators are Charles Holmes, an affiliate research professor the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Barbara Crass, a faculty researcher in the Department of Religious Studies and Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin - Oshkosh.

"This question is significant because it could provide further evidence that the first Americans were involved in the extinction of the woolly mammoth," Krasinski and Wygal told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mammoths went extinct at the end of the last ice age about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, although a small population of mammoths survived on Wrangel Island, off the Siberian coast, until about 3,700 years ago, Live Science previously reported. But the mammoth's extinction is still shrouded in mystery, and scientists continue to debate whether an abruptly warming climate, human hunters or a combination of both drove the animals to extinction.

In a study published in 2016 in the journal Science Advances, researchers suggested that a perfect storm of both factors doomed the ice age giants, but earlier works, such as a 2014 study published in the journal PLOS ONE, placed more of the blame on humans, Live Science previously reported.

"Such questions are essential to understanding the greater impact of people on their environments," Krasinski and Wygal wrote in the email. These questions may also help researchers understand "the timing and circumstances surrounding the initial peopling of the Americas from Asia," they said.

The finding has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The tusk is now at the Adelphi University archaeology laboratory, where it will undergo further analysis.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.