Culprit of Deadly Tibet Avalanche: Climate Change

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An avalanche of ice that killed nine in western Tibet may be a sign that climate change has come to the region, a new study finds.

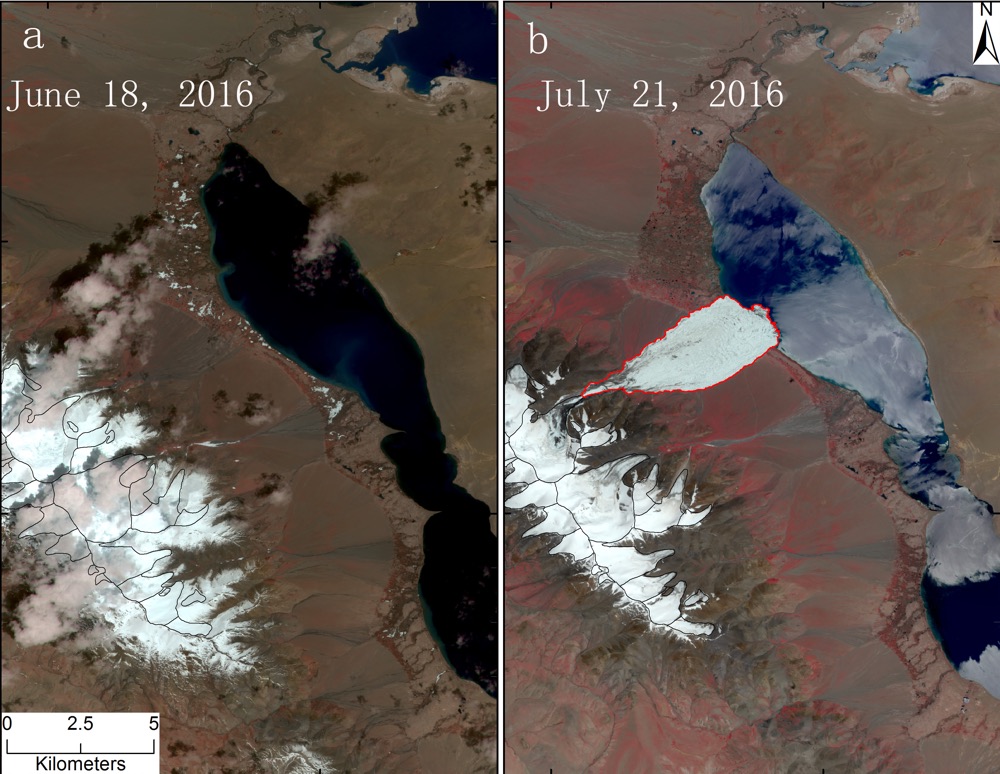

The avalanche at the Aru glacier in July 2016 was a massive event that spilled ice and rock 98 feet (30 meters) thick over an area of 4 square miles (10 square kilometers). Nine nomadic herders and many of their animals died during the 5-minute cataclysm. It was the second-biggest glacial avalanche ever recorded, and initially mystified scientists.

"This is new territory scientifically," Andreas Kääb, a glaciologist at the University of Oslo, said in a statement in September. "It is unknown why an entire glacier tongue would shear off like this." [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Now, an international group of scientists thinks they know the reason: Meltwater at the base of the glacier must have hastened the slide of the debris.

"Given the rate at which the event occurred and the area covered, I think it could only happen in the presence of meltwater," Lonnie Thompson, a professor of Earth sciences at The Ohio State University, said in a statement.

Thompson and his colleagues from the university's Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center worked with scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences to measure the icefall and recreate it with a computer model. They based the model on satellite and global position system (GPS) data, allowing for a precise understanding of how much debris fell.

The stimulations could only recreate the catastrophic collapse if meltwater was present. Liquid water at the base of a glacier speeds its advance by reducing friction, as is frequently seen in Greenland. Meltwater may also bring heat to the interior of the glacier, warming it from the inside, according to 2013 research on Greenland's glaciers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In western Tibet, the origin of the possible meltwater is unknown, Thompson said in the statement. However, the region is undoubtedly heating up.

"[G]iven that the average temperature at the nearest weather station has risen by about 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over the last 50 years, it makes sense that snow and ice are melting and the resulting water is seeping down beneath the glacier," Thompson said.

That's particularly alarming because western Tibet's glaciers have so far been stable in the face of warming temperatures, according to the researchers. In southern and eastern Tibet, the glaciers have been melting much more rapidly. Above-average snowfall in western Tibet has even expanded some glaciers, according to study author Lide Tian, a glaciologist at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Paradoxically, Tian said in a statement, that extra snowfall may have created more meltwater and made the devastating avalanche more likely.

A second avalanche hit just a few kilometers away in September 2016. No one was harmed in that icefall, but Kääb and his colleagues said that the two collapses, so close in time and space, were unprecedented.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus