In Photos: Diving in a Twilight Coral Reef

Sloping toward twilight

Most research on coral reefs has been done in shallow waters, where it's relatively easy to scuba dive. But there's a whole new world in the ocean's mesophotic zone, where only a small percentage of sunlight penetrates. Mesophotic reefs, also known as twilight reefs, exist in a perpetual state of dim blueness. Here, a reef in the northern Red sea slopes toward the mesophotic zone.

[Read the full story on the twilight coral reef]

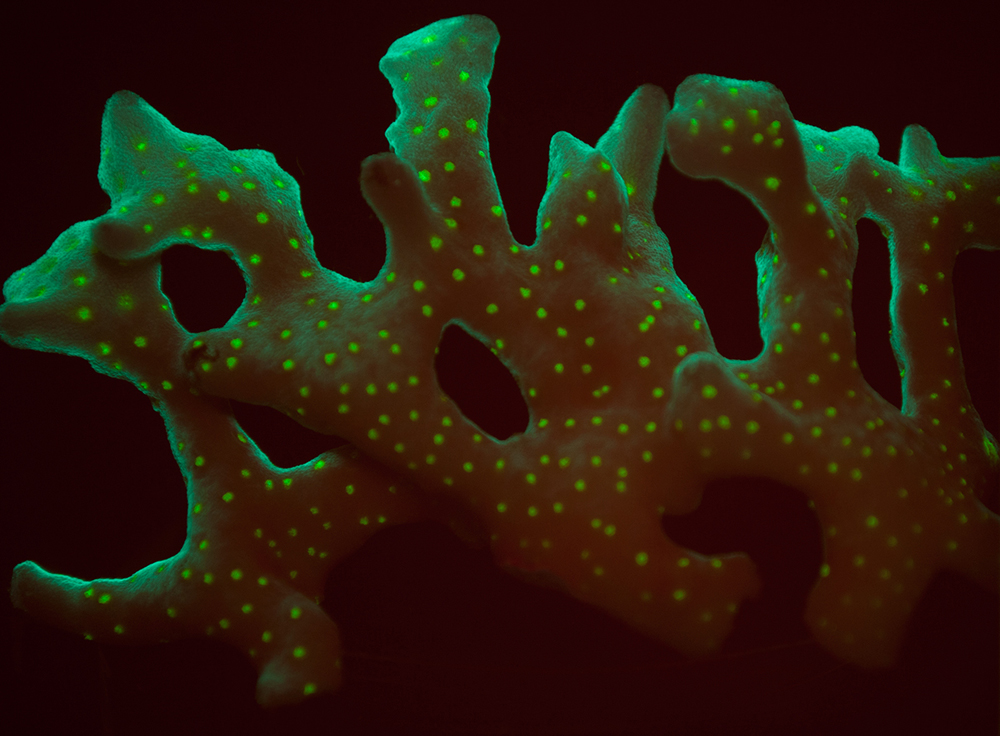

Bioflourescent coral

The corals in mesophotic reefs have evolved to thrive on photosynthesis, despite limited light. Here, a specimen of Stylophora coral fluoresces under ultraviolet light. New research published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science finds that the symbiotic algae inside these corals, whose photosynthesis powers the coral, have adapted the molecular machinery that turns sunlight into energy in order to make the process more efficient. These corals live in the northern Red Sea, off the coast of the city of Eilat, Israel.

Specialty diving

To dive to 213 feet (65 m), researchers must use specialty equipment. Commercial scuba divers don't usually dive below about 130 feet (40 meters). Here, marine scientists David Gruber and Oded Ben-Shaprut use rebreather systems with a mixture of three gases in order to decrease the risk of nitrogen narcosis, a dangerous drunken state caused by breathing nitrogen at high pressure. Divers can stay at mesophotic depth using these systems for up to an hour, Gruber told Live Science, but they usually spend less time than that. The longer they dive, the slower they must ascend to avoid decompression sickness, or "the bends."

Ready to dive

Marine biologist David Gruber of The City University of New York prepares for a dive to the mesophotic zone off of Eliat, Israel. Researchers conducted dives over the course of four years to study the corals in dim reefs. They gradually transferred deep corals shallow and shallow corals deep, moving the specimens a mere 16 feet (5 meters) every two weeks.

[Read the full story on the twilight coral reef]

A blue world

Only blue light can penetrate into the ocean's mesophotic zone. Here, divers explore a coral wall in this dim, blue world. Researchers found that shallow corals from about 10 feet (3 meters) depth could barely survive when brought down to 213 feet (65 meters). Deep corals brought to shallow waters died rapidly, though: They simply couldn’t take the intensity of the sun higher in the water column.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Deep dive

Marine scientist Shai Einbinder dives deep in the northern Red Sea to explore the physiology of corals adapted to dim light. Deep mesophotic reefs are little-explored compared to shallower, easier to reach reefs. They're too shallow for most remotely operated vehicles (which are expensive to use), and too deep for most scuba divers.

Bring your own light

Diver and marine biologist Shai Einbinder digs in his dive bag in the dim mesophotic zone of the northern Red Sea. Einbinder and other divers to this depth bring their own light, as only a very small amount of sunlight can penetrate down to 213 feet (65 meters), where much of this study was conducted.

[Read the full story on the twilight coral reef]

An unknown world

Marine biologist Shai Einbinder during a dive to the twilight reefs off the coast of Eilat, Isreal. Mesophotic reefs are found the world over. A recent study of reefs 300 feet (90 meters) down near Hawaii revealed colorful fish and meadows of gently waving algae. In the Red Sea, researchers discovered adaptations in the symbiotic algae in corals that have never been seen before in any photosynthetic organism.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus