Parkas Helped Early Humans Survive

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

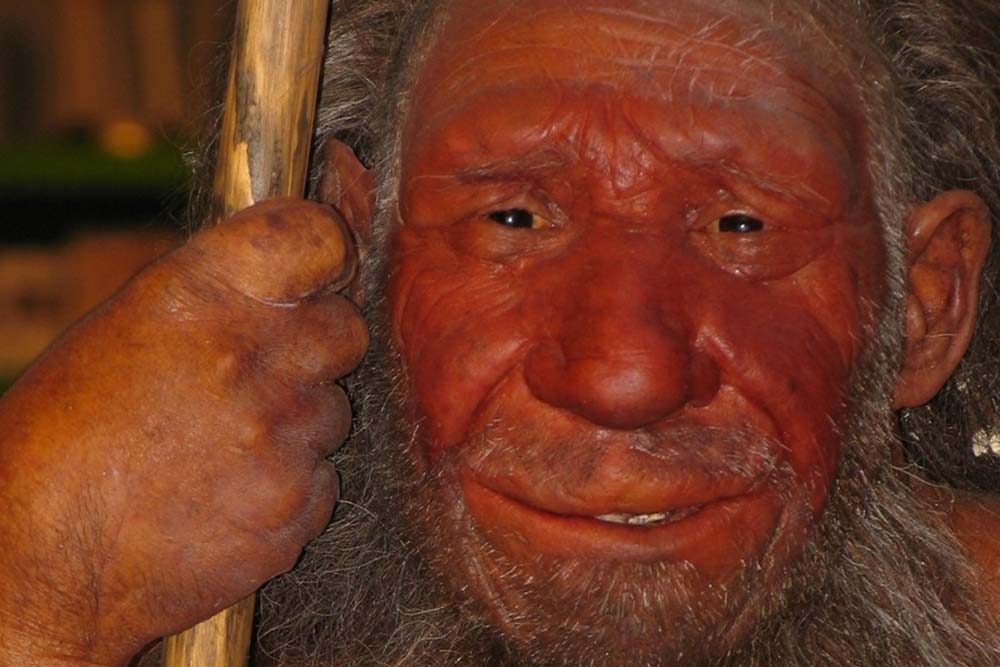

Fur clothing similar to modern-day parkas helped early modern humans survive the Ice Age, says a new study into prehistoric clothing.

Meanwhile, Neanderthals, who wore only cape-like clothing, remained exposed to the Ice Age chill.

Such clothing differences could have contributed to the demise of Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago.

To determine whether Neanderthals used clothing with the same thermal effectiveness as early modern humans, a team of researchers in Canada and Scotland investigated the bones of animals whose skins may have been used to produce clothing.

RELATED: Neanderthals in Belgium Were Cannibals

Led by Mark Collard, professor of archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, and a Canada Research Chair at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada, the team used an ethnographic database to identify animals that were used to create cold weather clothing in the recent past.

Then they compared the frequency of occurrence of these families in European archaeological deposits from three cultures: Mousterian, Aurignacian, or Gravettian.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Mousterian tool culture is associated with Neanderthals, while early modern humans are thought to have produced the Aurignacian and Gravettian.

"We obtained two main results. One is that mammalian families used for cold weather clothing occur in both early modern human and Neanderthal associated strata," the researchers wrote in the upcoming issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

"The other is that three of the families—leporids, canids and mustelids—occur more frequently in early modern human than in Neanderthal strata," they added.

In particular, 56 early human sites were found to contain wolverine, the fur of which was widely used as ruffs on parkas by recent sub-Arctic and Arctic groups. Not a single wolverine specimen was found at Neanderthal sites.

"Wolverine fur is the best natural fur to use as a Parka ruff. It provides excellent protection from the wind, sheds hoarfrost particularly well and is extremely durable," the researchers wrote.

The abundance of wolverine specimens in the Aurignacian and Gravettian sites and the complete lack of it in the Mousterian strata, suggests the use of prehistoric parkas in the Ice Age.

RELATED: Oldest Neanderthal DNA Sample Extracted in Italy

The researchers suggest that, like the Inuit, early modern humans in Europe added fur trim to their clothing to make high quality cold weather clothing. Neanderthals just wore cape-like clothing mainly from bovids and animals of the deer family.

"This difference would have had major implications for the ability of the two species to operate in cold weather," Collard told Discovery News.

He noted that prolonged exposure to cold in the absence of adequate clothing can lead to frostbite and hypothermia, and eventually, death.

But even if differences in clothing did not affect health and survival directly, they could have limited their ability to look for food, lowering energies and ultimately affecting the reproductive rate and demography.

RELATED: Your Brain Works Differently in Winter Than Summer

The reason for the clothing difference between Neanderthals and early modern humans is yet unclear.

According to one hypothesis, despite having brains similar in size to those of Homo sapiens, the Neanderthals were not intelligent enough to manufacture garments of the same thermal effectiveness as those used by early modern humans.

Alternatively, it is possible that the difference was purely cultural, Collard explained.

"There are examples from recent history of groups of Homo sapiens failing to adapt to changing environmental conditions because they didn't innovate and chose not to copy ways of doing things from other people. So, this is a real possibility," he said.

"Determining which of these hypotheses is correct will require further empirical research," Collard and colleagues concluded.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus