Geniuses are Just Like Us

Everyone has heard of the mad scientist or the absent-minded professor. But a look at some of the ordinary and extraordinary imperfections of a few great minds reveals that geniuses are just like us.

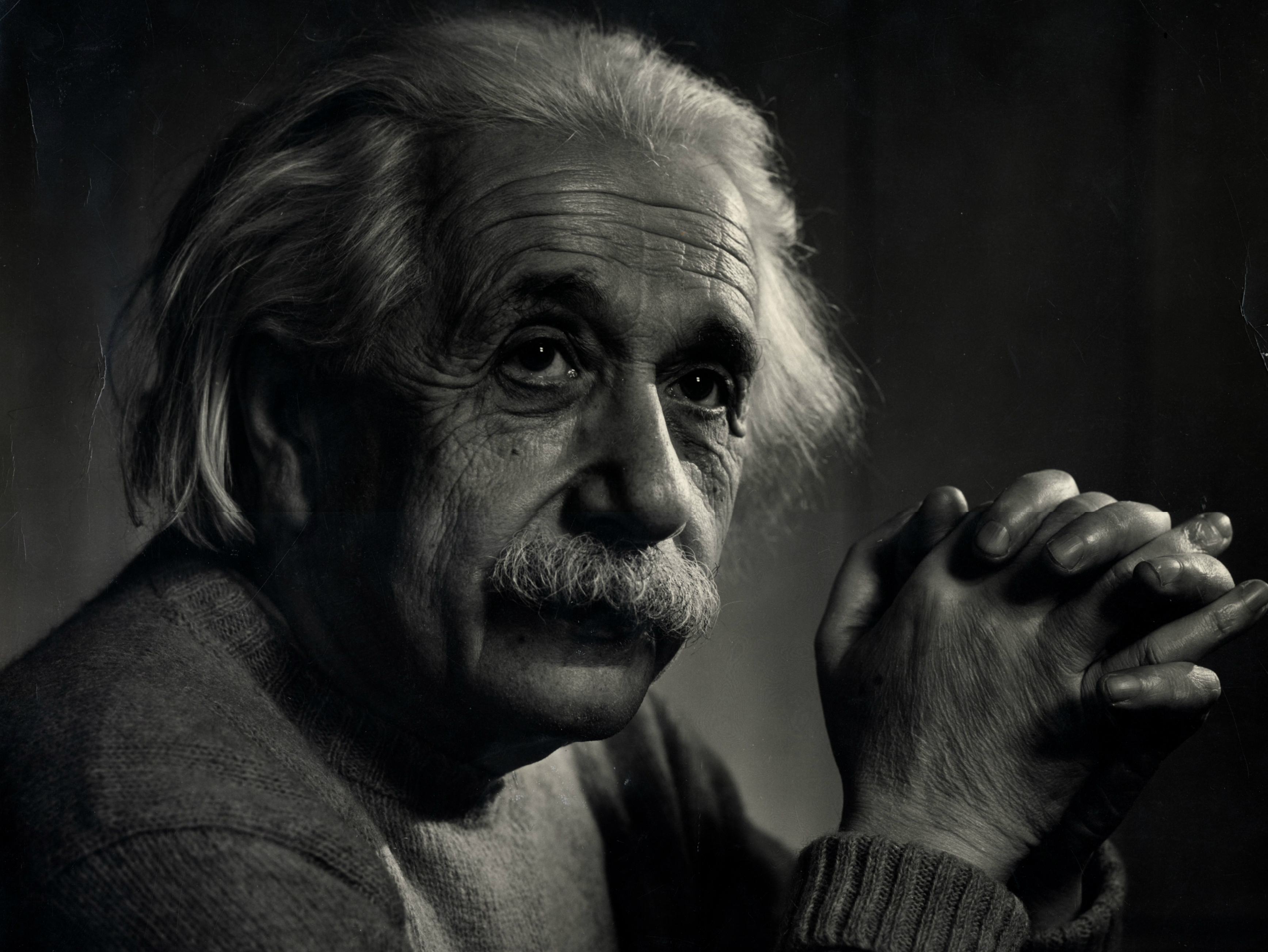

Albert Einstein, who came up with the theories of special and general relativity, enjoyed the company of other women while he was married. His second wife was his first cousin. He lived with her for five years before divorcing his first wife with whom he had a child before they were married.

Charles Darwin, father of evolutionary theory, agonized as a single man over whether or not to marry at all. He drew up a list of pros and cons, saying a wife was “better than a dog anyhow … but [a] terrible loss of time.” He married soon thereafter, his lifelong mate.

More of the same

Richard Feynman, a Nobel prize-winning physicist who helped develop the atomic bomb and figure out the source of the shuttle Challenger explosion, visited strip clubs nearly daily near his home in California. He mainly worked on lectures and equations there.

But for breaks, Feynman would watch the dancers and draw them. His wife, his third marriage by this time, was fine with this.

Sigmund Freud, who revealed the psychology of the unconscious in his numerous writings and was generally a nice guy, got into intense verbal scraps with his male friends due to his unresolved feelings of omnipotence, according to John Simmons, author of “The Scientific 100” (Citadel Press, 2000).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On the home front

Isaac Newton, who arrived at three laws of motion and a law of gravity that explained that the physical world was governed by mathematics, was reared by his grandmother after his father died and his mother remarried a man whom Newton loathed, Simmons writes.

Newton had a tendency toward unnecessarily bitter and violent rages with his colleagues and friends, and he did some mid-life career hopping, including a lackluster stint in Parliament.

Marie Curie, who discovered radioactivity, lived with her husband in a sparsely furnished apartment because she hated housework. While the couple did their research in a leaky shed, they had little money and would cheer themselves up by sitting next to the stove with a cup of hot tea. She later received two Nobel prizes.

Paul Erdos, one of the 20th century’s greatest mathematicians and whose work laid the foundations for computer science, lived out of a suitcase and was a poor earner for most of his life. He said property was a nuisance and relied on the kindness of friends for food and clothing.

What makes genius?

Not convinced that geniuses are just like us? Simmons says the true similarity lies in how nurture meets nature.

In other words, the talents that geniuses are born with, such as math, cognitive and creative skills, must be nurtured socially and economically in childhood or they die on the vine, with rare exceptions, Simmons told LiveScience.

Same goes for “the rest of us” and our slightly less spectacular talents.

“The scientific genius who grew up in grinding poverty is an exceedingly rare bird,” he said. “If it seems there was a great flowering of scientific genius out of Eastern Europe beginning in the late nineteenth century, it was due in large part to a developing middle class, a stable family life, and secular opportunities for both men and women."

- Vote Now: The Greatest Modern Minds

- Einstein Managed His Inbox Just Like You

- Smart People Choke Under Pressure

January is Genius Month at LiveScience.

Vote for the Greatest Modern Mind Ben Franklin Turns 300: Twice

In the Archives:

Smart People Choke Under Pressure Simple Writing Makes You Look Smart Expanse of Knowledge Delays Big Ideas Big Brains Not Always Better

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus