Updated at 10:45 a.m. E.T. on Aug. 27.

An ancient Greek palace filled with cultic objects and clay tablets written in a lost script may be the long-lost palace of Mycenaean Sparta, one of the most famous civilizations of ancient Greece.

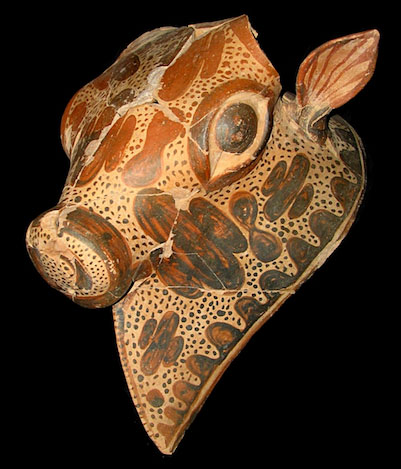

The 10-room complex, called Ayios Vassileios, was filled with striking artifacts, including fragments of ornate murals, a cultic cup with a bull's head, a seal emblazoned with a nautilus and several bronze swords. The palace, which burnt to the ground in the 14th century B.C., also contained several tablets written in Linear B script, the earliest known form of written Greek, the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement. The ancient palace was uncovered about 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) away from the historical Sparta that arose centuries later.

The discovery could shed light on a mysterious period in the history of the Mycenaean civilization, the Bronze Age culture that mysteriously collapsed in 1200 B.C. [See Photos of the Spartan Palace and Artifacts]

Mysterious Greek culture

The Mycenaeans, whose culture likely inspired Homer's epics "The Iliad" and "The Odyssey," rose to prominence in 1700 B.C. The civilization left behind gorgeous palaces, tombs laden with treasures and a trove of clay tablets holding text in Linear B, which was deciphered in the 1950s.

In one of history's enduring mysteries, the culture disappeared 500 years later and Greece entered a mini-dark age. Researchers, reporting in 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE, pinned the Mycenaeans' downfall on a 300-year drought, whereas other historians have proposed that a massive earthquake destroyed the civilization.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though archaeologists have a fairly clear picture of the late Mycenaean culture up to around 1200 B.C., they knew relatively little about the centuries beforehand. Then in 2009, archaeologists uncovered the remains of an ancient site that was first erected in the 17th century B.C., according to the statement. The entire complex was likely destroyed in a fire a few hundred years later. [7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Ancient Spartan palace?

The ruins, which are on a low hill on a Spartan plain that is dotted with olive trees, include what is likely the palace archive. At the time, administrators of the political bureaucracy kept temporary records on unbaked clay tablets, which would then be recycled after a short period, such as a year, said Hal Haskell, an archeologist who studies the ancient Mycenaean culture at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas.

Though the conflagration destroyed the palatial complex, it also fired the clay tablets, baking the Linear B text into permanence. So far, the team has been able to identify both male and female names, as well as records of financial dealings and religious offerings, according to the statement. The records' complexity reveals a highly sophisticated culture with an intricate bureaucracy, the archaeologists note.

A second structure on the site preserved fragments of ancient murals, while a sanctuary east of the courtyard included cultic religious objects, such as ivory idols and figurines, a rhyton, or drinking vessel, with a bull's head on it, large newts and many decorative gems.

The palatial complex fills a big gap in archaeology, said Haskell, who was not involved in the current excavation.

"Tradition tells us that Sparta was an important site in the Mycenaean period," Haskell told Live Science.

Yet no one had found a palace in the Spartan plain, certainly not one that matched the grandeur of the palaces of Pylos and Mycenae. The new site could be that lost Spartan palace, Haskell told Live Science.

"What's exciting is you do have this middle Bronze Age stuff that suggests it's a site of great significance," Haskell said, referring to the artifacts inside the palace.

For instance, Linear B tablets would only be housed in an administrative center in Mycenaean culture, Haskell said. To really show this is a long-lost Spartan palace, the archaeologists are hoping to uncover the megaron, or the throne room where ancient Greeks held receptions, Haskell said.

The find is "hugely significant," Torsten Meissner, a classicist at the University of Cambridge in England, told Live Science in an email. All of the other famous sites Homer mentioned in his epics have been discovered. "Mycenaean, or Bronze Age, Sparta was the last 'big prize,'" Meissner said.

The early evidence of Linear B tablets at the palace could also force scholars to rethink the time and place where Linear B developed. Historians used to think that Linear B derived from an elusive, still undecipherable text used by the enigmatic Minoan culture known as Linear A, which developed on the island of Crete. The new Linear B tablets at Ayios Vassileios were from 100 years earlier than the next oldest tablets, and given that there is a Minoan settlement near the new Spartan palace, scholars may need to rethink where that language transfer occurred, Meissner said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to note that the palace complex near Sparta burnt down in the 14th century B.C., not sometime between the 15th and 14th centuries B.C.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.