Photos: Stinky 'Corpse Flower' Blooms

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A towering corpse flower, or titan arum, is blooming in Denver. The teenage plant is a novice, as this is its first time opening up a flower bud, and generating the stinky rotting-flesh smell that attracts not only flies but also humans with cameras. Here's a look at the gorgeous flower, whose bloom is fleeting.

A strange creation

Visitors to the Denver Botanic Gardens take a gander at a giant corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum) that bloomed Aug. 19. This was the first bloom for the 13-year-old plant, which produces a smell like rotting meat meant to attract flies, beetles and other carrion-loving pollinators. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

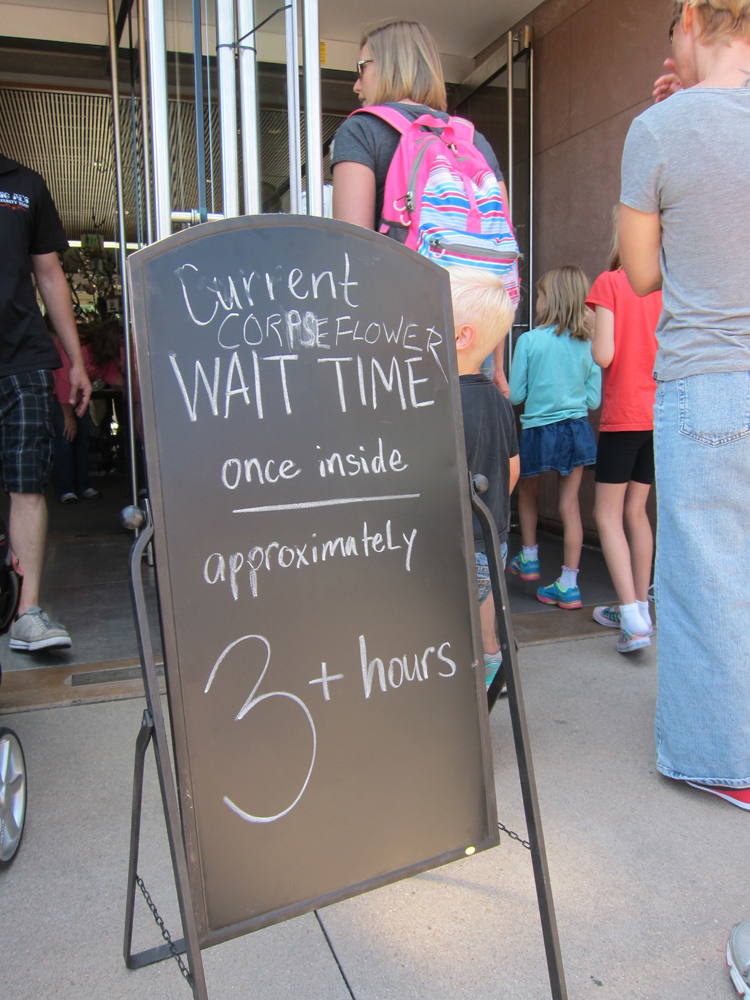

Worth the wait

The wait to see (and smell) Denver's first corpse flower bloom stretched more than three hours on Wednesday (August 19). Corpse flowers bloom for only about 48 hours before entering a dormant stage. The plants can go up to a decade before blossoming again. (Credit: Stephanie Pappas.)

Blooming in action

The first corpse flower bloom at Denver Botanic Gardens, as seen on the afternoon of August 19. The plant's skirt-like spathe began to unfurl in the evening on August 18, according to Garden staff. The bloom peaked in the early morning hours of August 19. The central stalk, called the spadix, is actually made up of hundreds of small flowers. This many-flowered structure is called an inflorescence. (Credit: Stephanie Pappas.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Waiting for a glance

A line winds its way through the grounds of the Denver Botanic Gardens, as visitors await a chance to see and smell the blooming Titan Arum, or corpse flower. These plants are native to Sumatra, Indonesia, and little is understood about their life cycles. Horticulturists can't predict a bloom until the plant produces a bud. The plant in Denver put out the unmistakable smell of rotting meat, best sniffed through the air vents at the back of the greenhouse. (Credit: Stephanie Pappas.)

Peeking inside

A view into the first-ever bloom by the 13-year-old Titan Arum plant at Denver Botanic Gardens. The maroon petal-like structure is called a spathe, and the yellow central stalk is called a spadix. Female flowers dot the bottom of the spadix; male flowers, which mature later to prevent self-pollination, are higher up. Insects have to crawl up the spadix to escape the plant, ensuring they get covered with pollen from the male flowers that they'll carry to the next blooming corpse flower. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

Is it hot in here?

An early-morning view of the Denver Botanic Gardens corpse flower. To better spread their noxious stench, the flowers actually heat up to human body temperature during a bloom. These blooms are extraordinarily energy-intensive to the plant, which is why they happen only every few years. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

Been around

This corpse flower has been at the Denver Botanic Gardens since 2007. As of August 18, the flower stood 5 feet and 3 inches tall, up from just over a foot less than a month before. The plant grew, on average, about 2 inches each day, said horticulturist Aaron Sedivy. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

Admiring the fruit of labor

Denver Botanic Gardens horticulturist Aaron Sedivy stands by the garden's corpse flower. Horticulturists have decided not to pollinate the flower, as the plant is young and putting out a seed would put it under stress. Sedivy said the plant might flower again in three to five years — or take as long as a decade. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

Thirsty little critter

A plant in profile. Corpse flowers are difficult to grow because they demand high humidity, Sedivy said. During their dormant stage, they need next to no water. But while they bloom, they require huge amounts. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

A public hit

The blooming corpse flower has drawn huge crowds to the Botanic Gardens. As of 11 a.m. on August 19, only two hours after the Gardens opened to the public (and 5 hours after it opened to members), more than 5,000 people had seen the Titan Arum, a Gardens spokeswoman said. (Credit: Scott Dressel-Martin.)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus