Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

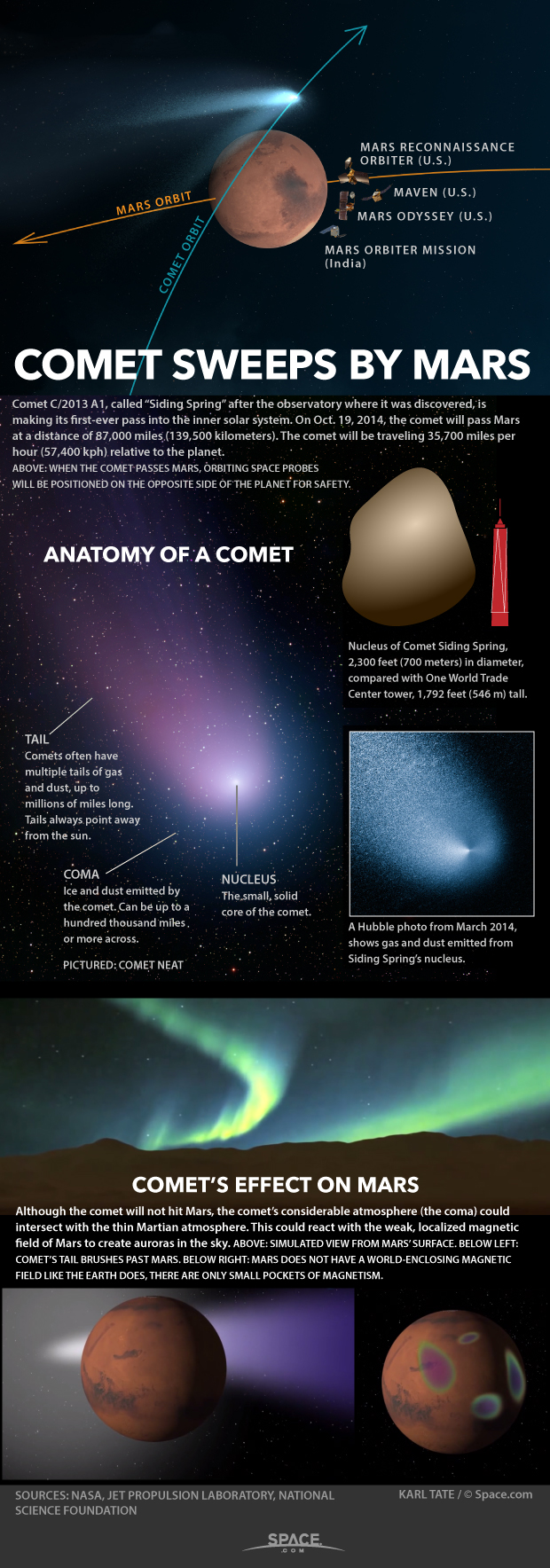

A comet's close shave with Mars this weekend could reveal some key insights about the Red Planet and the solar system's early days, researchers say.

Comet Siding Spring will zoom within 87,000 miles (139,500 kilometers) of Mars at 2:27 p.m. EDT (1827 GMT) on Sunday (Oct. 19). Scientists will observe the flyby using the fleet of spacecraft at Mars, studying the comet and any effects its particles have on the planet's thin atmosphere.

"On Oct. 19, we're going to observe an event that happens maybe once every million years," Jim Green, director of NASA's planetary science division, said in a news conference earlier this month. "This is an absolutely spectacular event." [See photos of Comet Siding Spring]

A pristine comet

Siding Spring, whose core is 0.5 to 5 miles (0.8 to 8 km) wide, likely formed somewhere between Jupiter and Neptune about 4.6 billion years ago — just a few million years after the solar system began coming together.

Many of the objects in the region where the comet was born were incorporated into newly forming planets, but a different fate awaited Siding Spring, researchers said: It apparently had a close encounter with one of these planets and was booted out into the Oort Cloud, a frigid comet repository at the very outer reaches of the solar system.

For billions of years, Siding Spring came no closer to the sun than the realm of the giant planets (Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune). But a million years ago or so, a star passing by the Oort Cloud likely jolted the comet's orbit again, sending it on its first-ever trip into the inner solar system.

The comet's history helps explain why scientists are so excited about its current journey: Since Siding Spring has never been "heat-treated" by the sun before, it's a pristine object that looks much the same today as it did 4.6 billion years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If we study the comet — its composition, its structure — it will tell us a lot about how we think maybe the planets were formed," said Carey Lisse, a senior astrophysicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

While several NASA missions — such as Deep Space 1 and Deep Impact — have visited comets up close, none have gotten a good look at a pristine Oort Cloud comet before, Lisse said.

"We can't get to an Oort Cloud comet with our current rockets. These orbits are very long and extended, at very great velocities," he said. "So this comet is coming to us. It's a free flyby, if you will, and that's a very fantastic event for us to study."

The interaction between Mars' upper atmosphere and the particles shed by Siding Spring should also reveal insights about the Red Planet's air, researchers said.

A coordinated campaign

All of the operational spacecraft at Mars will attempt to observe Sunday's flyby. NASA's Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and newly arrived MAVEN probe will watch from Mars orbit, as will India's Mangalyaan spacecraft and Europe's Mars Express. And NASA's Curiosity and Opportunity rovers will point their cameras skyward from the Red Planet's surface.

MRO may capture the first resolved images of an Oort Cloud comet's core, researchers said. The rovers could make some history as well — if the Martian weather cooperates.

"This is kind of a dusty season on Mars, too, and so the dust is going to make the comet even less bright" from the Red Planet's surface, said Kelly Fast, program scientist at NASA's planetary science division. But, she added, "we certainly have fingers crossed for the first images of a comet from the surface of another world."

The risk of any damage to the Mars orbiters from comet dust is minimal, spacecraft operators say, especially since the probes have all been moved such that the planet will shield them during the time of highest exposure. The rovers have nothing to worry about, since Mars' atmosphere will protect them.

The Siding Spring observation campaign is not limited to Sunday's flyby. Researchers have already been studying the comet with a variety of ground- and space-based instruments, and they'll continue to watch after Siding Spring leaves Mars behind. (The comet's closest approach to the sun comes on Oct. 25, after which it will head back toward the Oort Cloud.)

"Assuming it survives the Mars encounter, we're actually going to watch and see if there've been any changes because of this passage through the inner [solar] system," Lisse said. "Following this comet back out again will be very important, as well as the flyby by Mars."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus