Puzzling New Animals Look Like Deep-Sea Mushrooms

Mysterious animals discovered offshore Australia resemble floppy chanterelle mushrooms but feel like dollops of gelatin, according to a new study.

The ocean-dwelling creatures are so unusual that an entire new taxonomic family was created to classify them, scientists report today (Sept. 3) in the journal PLOS ONE. Yet nothing is known about their lifestyle, their feeding habits, how they reproduce or if they float or attach to the seafloor.

"We don't even know if they're upside down," said lead study author Jean Just, a taxonomist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

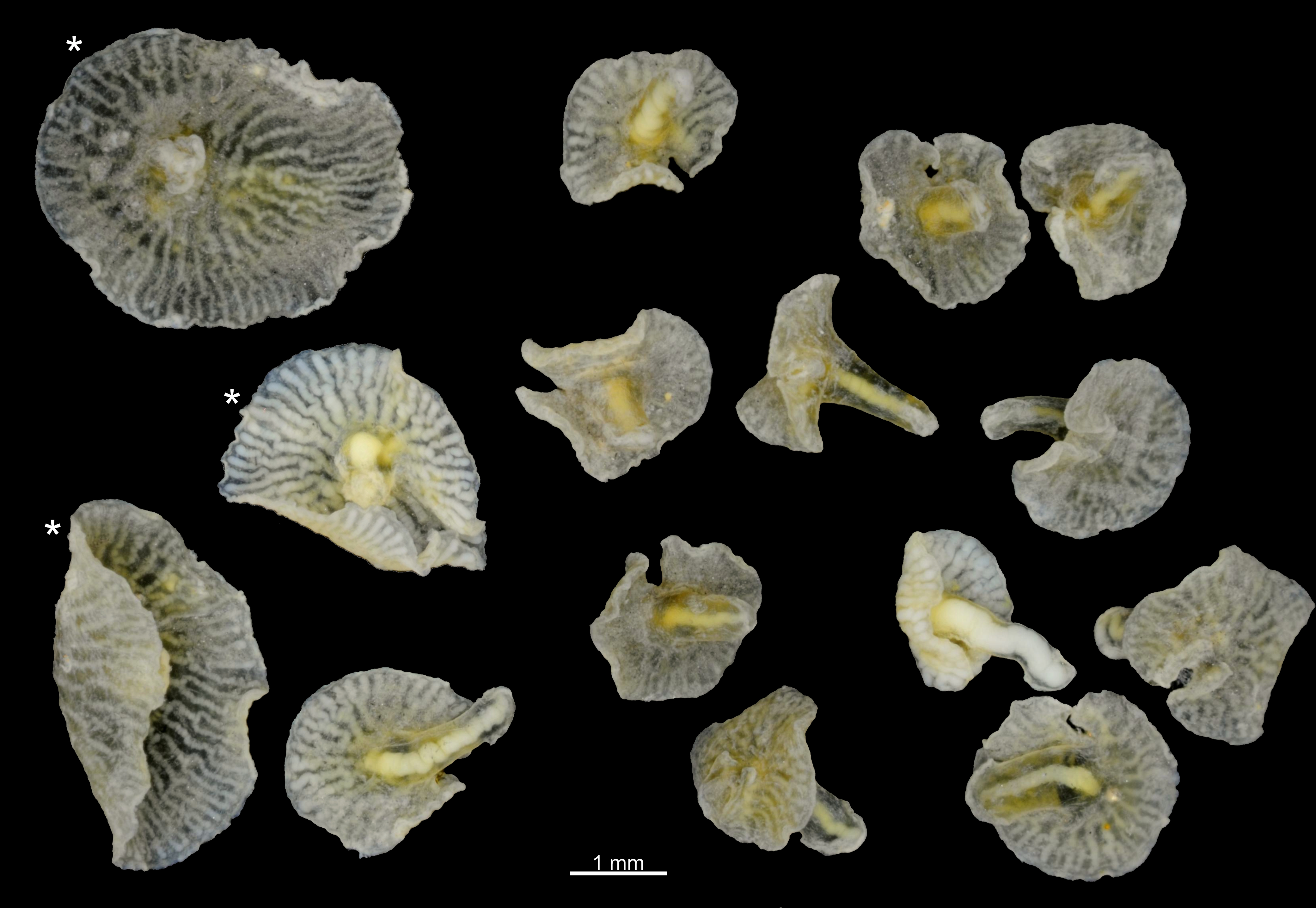

The two new species described in the study were officially named Dendrogramma enigmatica and Dendrogramma discoides. Their tops are flat discs about 0.5 inches (about 1 centimeter) wide. Inside the discs, a fan of digestive tubes delivers nutrients, radiating outward like bicycle tire spokes. The center "mouth" opens into the stalk, and is probably for both eating food and excreting waste, Just said. (Many primitive species have this single gut.) Of the two new species, one has a shorter stalk and smaller disc compared with the other, though the difference is only a few millimeters. [Image Gallery: Mysterious Ocean-Dwelling 'Mushrooms']

Only 18 Dendrogramma specimens exist; they were all caught in 1988 on a research ship exploring the eastern Bass Strait between Australia and Tasmania. The weird creatures were found in a mix of seawater and sediment scooped from 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) below the ocean surface.

After returning to shore, scientists sifted through the marine life collected during the research cruise. Just, who was then at Australia's Museum Victoria in Melbourne, said he recognized the creatures were strange and special, but thought they were a new kind of jellyfish.

However, a closer look revealed no stinging cells, the hallmark of true jellyfish. No tentacles dangle from the Dendrogramma, and their tiny, hairless bodies also lack the swimming cilia that define comb jellies, another type of translucent ocean blob.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They lack all of the characteristics that would put them in one phylum or another," Just told Live Science. "I think their closest relatives are probably the Cnidaria [true jellyfish] and the comb jellies, even if we can't place them in either of those phyla."

(A phylum is a taxonomic group one level below a kingdom. Humans and jellyfish are both in the kingdom Animalia, for instance.)

Instead, both of the strange new species bear an uncanny resemblance to several 600-million-year-old Ediacaran fossils, the earliest animals. One Ediacaran form had an identical three-lobed disc with a stalk, with exactly the same gut branches as Dendrogramma, Just said. The Ediacaran fossils were first discovered in Australia, but whether the new species are incredible living fossils or simply evolutionary mimics may never be answered. "They have some really remarkable similarities, but there is no way of telling whether they are a living link," Just said.

Scientists have estimated that as many as 600,000 new species remain undiscovered in the ocean.

No genetic data exists to help place Dendrogramma in the tree of life. The deep-sea "mushrooms" were preserved in chemicals that destroyed their DNA and cells, hampering classification. Just said he hopes more tiny Jell-O-like creatureswill someday surface in another deep-sea expedition so modern genetic studies can reveal their evolutionary branch.

"These are primitive organisms at the bottom of the tree of life," Just said. "No other living animals have these characteristics, so they are pretty special one way or another."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.