Fight Against Rheumatoid Arthritis May Unlock Secrets to Heart Disease and Depression (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

“Arthritis is for old people, right?”

This is an outdated view of a spectrum of diseases that affect people of all ages in the population. In the past decade, there has been a revolution in the understanding and treatment of many forms of arthritis, particularly one devastating variety, namely rheumatoid.

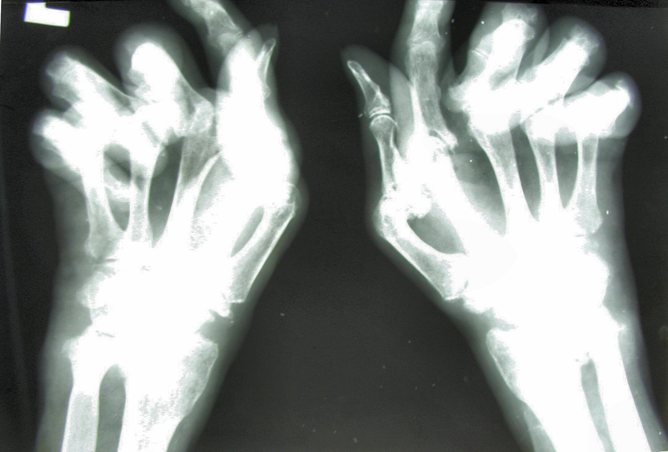

So what is rheumatoid arthritis? Those afflicted suffer pain, swelling and progressive deformity of joints if untreated.

The core problem seems to be uncontrolled inflammation – the immune system that normally faithfully defends us against infection turns its offensive molecular and cellular power upon the joints, which leads to substantial damage.

Counting the cost

There is no cure. Rheumatoid arthritis progresses inexorably over time, causing sufferers to lose function, independence and ultimately years of life expectancy. The disease is associated with loss of work productivity, employability and increased health care costs, so there is also an increased financial burden on family and community.

The disease’s first existence is found in bone remains located in Alabama dating back thousands of years. It emerges in Europe depicted in visual arts around the 15th century.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Quite why this transition from “new” to “old” world occurred is uncertain. Intriguingly this corresponds to early voyages of discovery with commencement of trade, particularly of tobacco, and consequent movement and mixing of populations.

Recent landmark studies clearly associate the risk of getting rheumatoid arthritis with smoking both directly and passively. Those with the disease who smoke are considerably less likely to respond to therapy. Some estimate that smoking cessation could reduce the future disease burden by up to 30%.

A second major advance has been new understanding of the vital importance of the bacteria we all carry in our gastrointestinal tract – the “human microbiome”. Variations in these bacterial populations are now associated with development of several diseases related to immune dysfunction.

New data suggests a link between rheumatoid arthritis and these variations. But the value of this for diagnosis or treatment is unknown and many more studies will be required.

Building on the Human Genome Project there are also now many large datasets informing us of the genes that increase our risk of developing the disease. Putting all of this together, it may be possible in the future to identify those at most risk and even consider preventative strategies.

This will take bold, imaginative studies that can drive a change in thinking by doctors and patients. How will we consider the relative benefits and risks of therapies that could prevent chronic inflammatory conditions previously thought to be incurable? How will we consider the cost of such innovations?

Inflammation and other diseases

A vital recent discovery has been that rheumatoid arthritis brings medical challenges beyond the joint. It also increases the risks of heart attacks, strokes, depression, poor concentration and bone fractures via accelerated osteoporosis (bone thinning). The mechanisms underlying these phenomena are not entirely clear but seem to emanate from the same inflammatory pathways that drive the primary attack on the joint.

Unravelling these pathways will be important not only to reduce risks in sufferers, but also because these pathways illuminate the potential mechanisms that could operate in the wider primary diseases of these tissues. There are already many studies that implicate inflammation in atherosclerosis (narrowing of the arteries) and coronary heart disease (leading to angina and heart attacks).

These discoveries are likely to lead to new and exciting preventative and therapeutic strategies that could impact millions of the population. Similarly inflammatory pathways are implicated in a variety of mood disorders, especially depression, raising hopes of new treatment options for these most difficult of human conditions.

While all this has been happening, two fundamental developments have led to a revolution in treatment over the past decade. The first is a change in the strategic approach to how the disease is managed. Rheumatologists now choose clear targets for treatment and adhere to widely endorsed treatment guidelines and algorithms.

The second development has been the advent of a variety of new medicines that capitalise on the explosion of knowledge about the pathology of the disease, in a sign that modern molecular medicine is truly delivering.

These new medicines include small chemical drugs and larger biologic drugs – the latter are proteins that mimic those that operate in the immune system itself. These have brought substantial improvements in outcomes.

But unmet needs remain. Few patients respond sufficiently well, and most require continuous therapy with only a modest proportion actually achieving a sustained remission. This means that most live with their disease improved but not cured. New therapies are expensive and fierce debates rage as to their relative health benefits and clinical effectiveness.

Ultimately we will seek stratified or personalised medicines for these diseases. Treatment will be about whether we give the right medicine to the right patient at the right time to maximise the benefit and minimise the risk.

Iain McInnes has consulted recently for companies that make medicines that are used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, including Abbvie, BMS, Pfizer, UCB. Iain through the University of Glasgow has received research grants from MRC, Arthritis Research UK and Nuffield Foundation and from Pfizer, BMS and UCB.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus