Arctic's 'Layer Cake' Atmosphere Blamed for Rapid Warming

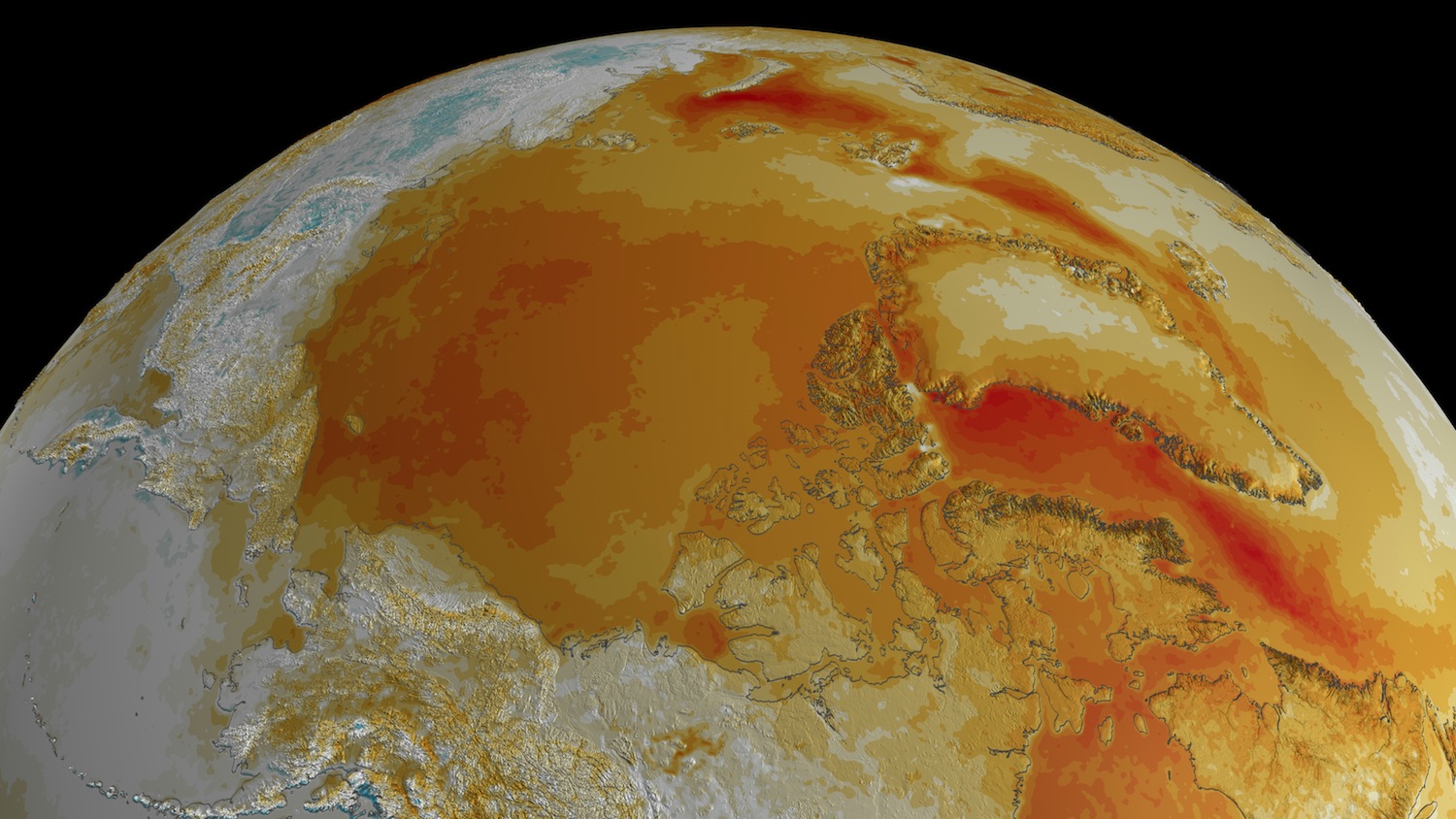

The Arctic is leading a race with few winners, warming twice as fast as the rest of the Earth. Loss of snow and ice, which reflect the sun's energy, is usually blamed for the Arctic temperature spike.

But a new study suggests the Arctic's cap of cold, layered air plays a more important role in boosting polar warming than does its shrinking ice and snow cover. A layer of shallow, stagnant air acts like a lid, concentrating heat near the surface, researchers report today (Feb. 2) in the journal Nature Geoscience. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

"In the Arctic, as the climate warms, most of the additional heat remains trapped in a shallow layer of the atmosphere close to the ground, not deeper than 1 or 2 kilometers [0.6 to 1.2 miles]," said Felix Pithan, a climate scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany and lead author of the new study.

"[This] makes the Arctic surface rather inefficient at getting rid of extra energy, and therefore it warms more than other regions when the entire planet is warming," Pithan told Live Science.

The Arctic atmosphere looks like a layer cake compared with the tropics. In those regions, thunderstorms carry heat from the surface miles upward, where it then radiates out into space. But in the Arctic, air and heat at the surface rarely mix with air located high in the atmosphere, Pithan said.

"The Arctic atmosphere is much more inefficient than the tropics at getting rid of that extra energy," he said.

This pattern also helps explain why the Arctic warming signal is stronger in winter, Pithan said. During that season, the Arctic air mixes less than in the summer, because of cold temperatures and inversion layers — places where air temperature increases with height, instead of the other way around.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Feedback loops

Pithan and co-author Thorsten Mauritsen tested air layering and many other Arctic climate feedback effects using sophisticated climate computer models. On a regional scale, climate feedback effects can amplify or dampen the global warming caused by greenhouse gases.

In the Arctic, one familiar feedback effect is sea ice albedo, which measures how well the Earth's surface reflects sunlight. Snow-covered ice reflects up to 85 percent of sunlight. But the Arctic sea ice has hit near-record minimums of sea ice since 2002, meaning the ocean is absorbing more sunlight, and heat, than it used to, leading to more ice melt.

The ice-albedo effect was the second most important contributor to Arctic warming, according to the study.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.