SAN FRANCISCO — It's time to accept reality: Comet ISON is dead.

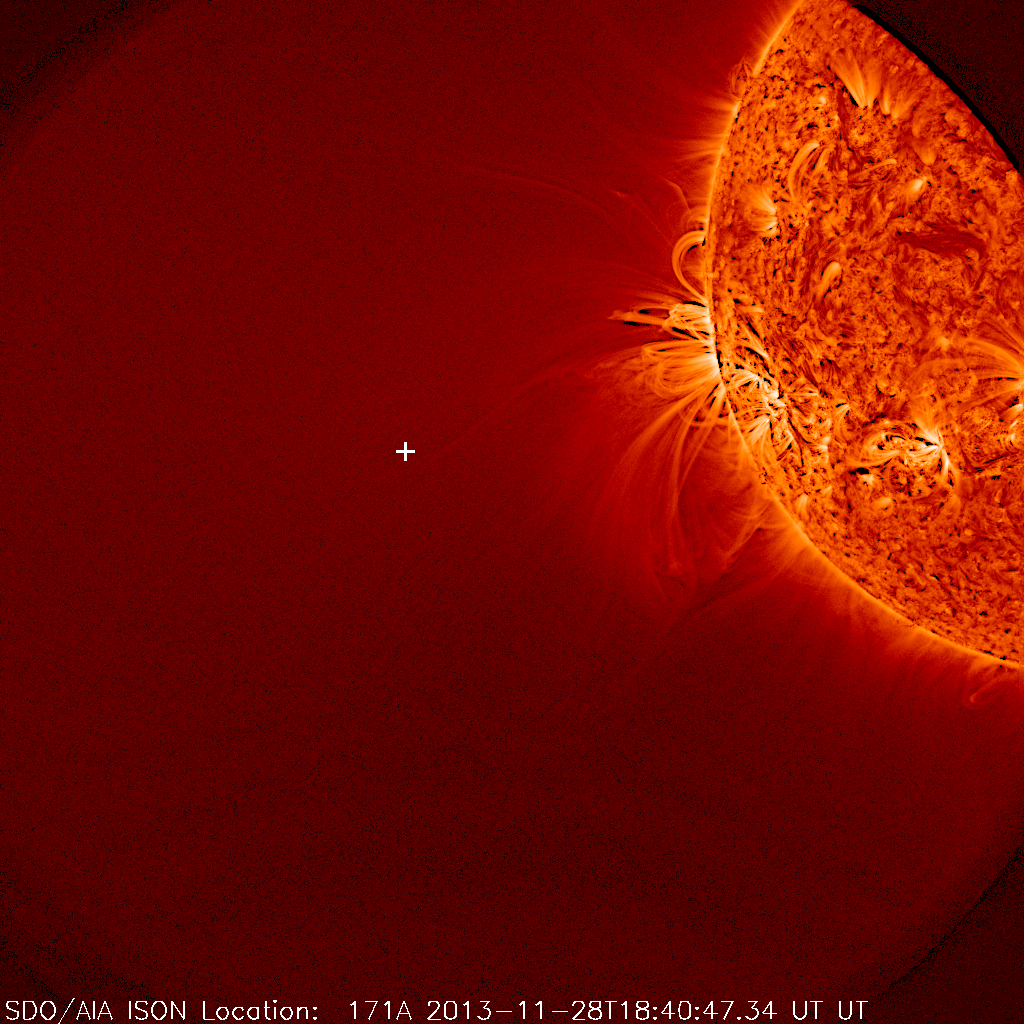

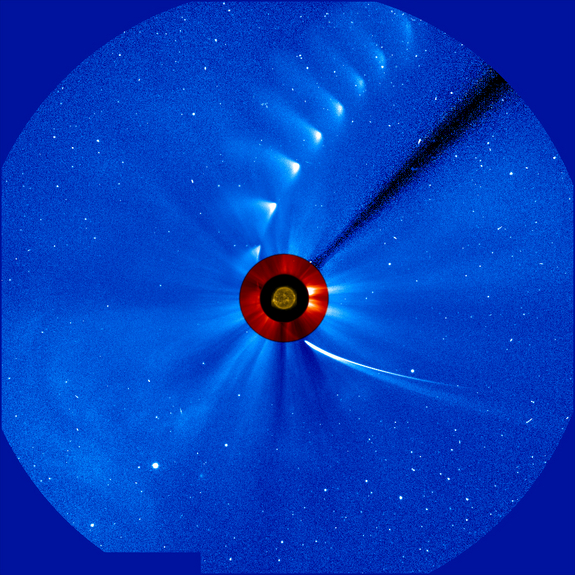

Comet ISON broke apart during its highly anticipated solar flyby on Nov. 28, emerging from behind the sun as a diffuse cloud of dust that has since all but dissipated in the darkness of deep space, scientists say.

"At this point, it seems like there's nothing left," comet expert Karl Battams, of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., said here today at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. "Comet ISON is dead; its memory will live on." [See the latest photos of Comet ISON]

Comet ISON, which was discovered by two Russian amateur astronomers in September 2012, was making its first trip to the inner solar system from the distant and frigid Oort Cloud. The comet skimmed just 684,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) above the surface of the sun on Nov. 28.

Comet ISON's perilous journey was tracked closely by skywatchers, who hoped the icy wanderer would put on a great celestial show, and scientists, who watched the gases boiling off ISON to learn more about comet composition and structure.

Both groups had hoped the viewing campaign would last beyond perihelion, or closest approach, but Comet ISON couldn't survive the sun's intense heat and powerful gravitational pull.

"It looks like dust production more or less stopped when the comet reached perihelion," said Geraint Jones of University College London. "The comet continued to fade after perihelion, as it moved away from the sun."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ISON gave one tantalizing hint that it may still be intact, brightening considerably a few hours after the perihelion passage. But that may simply have been a consequence of orbital dynamics and nothing more, Jones said.

Comet ISON's fragment cloud likely stretched out as the icy object reached perihelion, with the more anterior pieces speeding up relative to the ones farther behind, Jones explained. This would have caused ISON to dim, and then re-brighten briefly as the fragments clumped up again on the other side of the sun.

Comet behavior is incredibly difficult to predict, so it's tough to know exactly why ISON didn't make it. But its disintegration may have something to do with the comet's relatively small size. Recent observations by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) suggest that ISON's nucleus was between 330 feet and 3,300 feet (100 to 1,0000 meters) wide, scientists said today.

"It was probably smaller than maybe 600 meters [in] diameter," said Alfred McEwen of the University of Arizona, principal investigator of MRO's powerful HiRISE camera. "And from past sungrazing comets, those smaller than about half a kilometer, they don't survive."

While Battams and other experts have said their farewells to ISON, several NASA space telescopes will continue scanning the heavens just in case the comet makes a miraculous reappearance.

"NASA is going to try to look for it with Hubble, and I've heard that Spitzer and Chandra may be attempting observations as well," Battams said. "That really is sort of a recovery mission, but I don't know if we're going to get any success with those."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.