Possible Male Birth Control Blocks Sperm

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

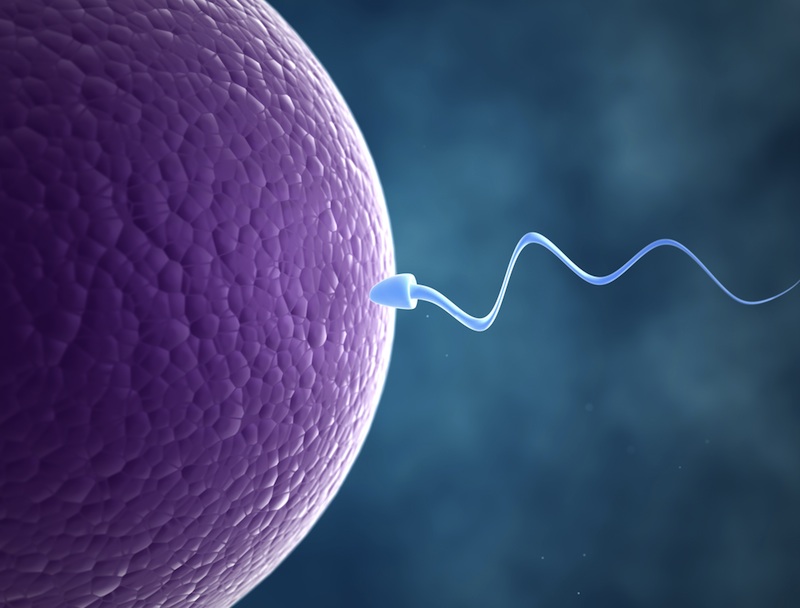

Keeping sperm from being ejaculated may provide the key to creating a birth control drug for men, according to a new mouse study.

The research is far from translating to a pill that human males could pop to keep from making babies; to reach that stage, any drug would have to undergo years of testing for safety and effectiveness. Nevertheless, the study offers hope for a new method of birth control for men, the researchers said.

"The search for a viable male contraceptive target has been a medical challenge for many years," Sabatino Ventura of Monash University in Australia and colleagues wrote today (Dec. 2) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The challenges of male birth control

Compared with female birth control, the male version is a biological challenge. Instead of stopping one egg, male birth control would have to stop each of the 1,500 sperm cells men produce each second. Early tests have proven hormonal methods to be clumsy, causing too many side effects. Attempts at halting the rapid production of sperm is similarly difficult, in part because a natural barrier between the blood and the testis, the site of sperm production, keeps drugs out.

To be popular, any anti-sperm birth control method would also need to be reversible, and could not cause long-term damage to sperm cells, lest it lead to birth defects when a man did decide to have children. [Sexy Swimmers: 7 Facts About Sperm]

The new study attempts another path: Instead of blocking the production of sperm, researchers are now trying to block its transport.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stopping sperm

Sperm are made in the testes, and stored in a tightly coiled tube called the epididymis, inside the testicles. When a man ejaculates, smooth muscle propels the sperm out of the epididymis, through a tube called the vas deferens, into the urethra and out of the body. Receptors on the muscles receive hormonal signals that instruct the muscles to contract, sending the sperm on its way.

Previous attempts to block these receptors, known as α1A-adrenoceptors and P2X1-purinoceptors, had decreased male fertility, but not entirely — male mice with blocked receptors could still father offspring up to 50 percent of the time.

But such studies had attempted to block only one of the two types of receptors. Most likely, Ventura and his colleagues reasoned, the body could compensate by beefing up the unblocked kind.

In the new study, the researchers bred mice that lacked both α1A-adrenoceptors and P2X1-purinoceptors. They found that female mice without the receptors could still reproduce as normal. Male mice pursued females and mated with them as usual, but they never sired babies.

A male pill?

A closer look revealed that the male mice without the receptors produced normal sperm, and when that sperm was used in artificial insemination attempts, it resulted in normal baby mice. The mice's vas deferens, however, did not contract normally in response to stimulation, suggesting that the lack of receptors did stop sperm movement.

The two blocked receptors are also important for cardiovascular health, but the mice showed few side effects beyond a 10-percent decrease in blood pressure, the researchers found. More work on side effects will need to be done, but the study suggests that men taking drugs to block the receptors would not be in danger, the researchers wrote.

The vas deferens is located outside of the blood-testis barrier, meaning that oral contraceptives targeting the receptors could easily reach their target. In fact, drugs that block α1A-adrenoceptors are already on the market to treat benign prostate enlargement.

A drug that blocks the P2X1-purinoceptor would still need to be developed and tested.

Of course, even if a combination α1A-adrenoceptor and P2X1-purinoceptor–blocking drug were developed, men would have to be on board, psychologically. The anti- α1A-adrenoceptor drugs already on the market have the side effect of the occasional orgasm without ejaculation.

"A lack of ejaculate has the potential to be disconcerting," the researchers wrote in their study.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus